The news media have been full of speculation about what caused an Amtrak train to derail east of Philadelphia on May 12, killing at least eight people and injuring hundreds.

Train #188, operated by lone engineer Brandon Bostian, entered a curve with a speed limit of 50 miles per hour, at over 100.

Was this excessive speed the result of fatigue, inattentiveness, a projectile that hit the train (and possibly the engineer), or some other factor? The investigation may eventually pinpoint the cause—or we may never know.

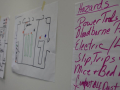

Safety Measures Needed

The rank-and-file group Railroad Workers United believes these simple steps would go a long way toward preventing train wrecks:

- Apply Positive Train Control technology on major rail routes as soon as possible.

- In the meantime, apply off-the-shelf, readily available technology at critical locations where passenger trains are particularly vulnerable.

- Require a minimum of two qualified employees—at least one certified locomotive engineer and one certified conductor—on every train.

- Guarantee adequate and proper rest, together with reasonable attendance policies and provision for necessary time off work, for all train and engine employees.

- Limit the length and tonnage of freight trains to a reasonable, manageable level.

- Focus safety programs on hazard identification and elimination, rather than worker behavior.

- Strengthen whistleblower laws to empower employees to report injuries, hazards, and safety violations without fear of company reprisal.

But we do know this: had there been a second crew member in the cab, it’s very likely that person would have taken action to prevent the tragedy when, for whatever reason, the engineer at the controls could not.

And blaming a worker just distracts the public from eliminating the real hazards. There exists simple, affordable technology that Amtrak could and should have implemented years ago—which could have prevented this terrible wreck.

UPGRADES BADLY NEEDED

It’s roundly agreed by railroad executives, union officials, and industry insiders that the May 12 wreck would probably have been impossible if Positive Train Control had been in effect on this section of track.

PTC is an electronic system that senses if a train is moving too fast or does not have authority to occupy a certain section of the track. It would have recognized that the train was going too fast to negotiate the tight curve ahead—and applied the brakes to slow it down.

Even without PTC, there’s simple technology to help prevent this kind of accident. Cab signals, in use on the Northeast Corridor for nearly a century, can automatically apply the brakes to enforce the speed limit on a given section of track. If there had been a cab signal in place, it could have enforced the 50 mph speed limit on the approach to this tight curve.

Since the accident, such a device has apparently been installed. Ironically, just 18 months earlier, Metro North was mandated to install a similar device in advance of a 30 mph curve at Spuyten Duyvil, New York—after a December 2013 wreck there.

UNDERFUNDED

Congress has mandated that freight and passenger railroads adopt PTC by the end of the year on tens of thousands of miles of mainline trackage. But Amtrak hasn’t completely implemented it in the busy Northeast Corridor, where this train wrecked, and elsewhere—partly because Congress hasn’t allocated enough money to do it.

Amtrak has been underfunded for decades. It’s forced to scrape by, cutting corners and deferring maintenance, always under the microscope of a budget-cutting Congress. Its budget is allocated yearly, making long-term capital investments difficult.

That means the company has a backlog of urgently needed repairs to bridges and tunnels. Many rail junctions and cross-over locations are obsolete. At times, trains rely on 1930s-era components.

What’s Wrong with Inward-Facing Cameras?

Recent train wrecks have fueled a call for inward-facing cameras on railroad locomotives. Railroad executives claim that these cameras will help them understand, after a wreck, what the crew did (or didn’t do) wrong.

Of course, cameras do nothing to address the underlying hazards that cause crashes. In fact, the cameras themselves could become intrusive, irritating, distracting—and possibly downright dangerous.

In difficult or confusing situations, engineers and conductors need to feel free to speak candidly and decide the best course of action together. They shouldn’t be distracted worrying about reprisals from the company when it reviews the film.

Imagine a crew member who makes a mistake. Aware that she’s been caught on camera, she may be distracted by worrying about it the rest of the trip.

Or imagine a whistleblower who’s been generating bad publicity by speaking up on a safety issue. The company could pore over hours of footage until it found something it could pin on him.

The rail carriers could easily abuse camera footage to spy on, intimidate, harass, discipline, and terminate employees—including for reasons that have nothing to do with any wreck. So if these cameras are installed, we need strict regulations limiting how they’re used.

Railroad Workers United is considering a draft resolution that calls for only post-accident investigation teams—not just any old supervisor or manager—to be allowed to view the camera footage, and for the recordings to be destroyed within a reasonable time after a trip if no accident or unusual event has occurred.

Federal funding will only cover a fraction of the $52 billion Amtrak forecasts it will need between 2010 and 2030 to install PTC and repair infrastructure on the Northeast Corridor.

NEW SCHEDULE

Making matters worse, just six weeks before the wreck, Amtrak had unilaterally implemented a new cost-cutting schedule for train and engine crews in the Northeast Corridor, over the vehement objections of its operating craft unions, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and the United Transportation Union (now known as SMART).

Both unions condemned the new schedule—designed to save $3 million by reducing layovers—as a disaster in the making.

A tried and true system of scheduling, where crews were assigned to trains out and back, had been in effect for decades. These schedules adhered to a 90-minute layover minimum to give crews a rest break. Schedules also took into account the duration of the trip, the number and location of stops, and the average timeliness of the route.

Now, not only has the 90-minute layover been scrapped, but crews have no guarantee of any break whatsoever.

The new arrangement also allows for a different on-duty time each day of the work week. Start times can now be any time of day.

The engineer of Train #188 had experienced a non-routine westbound trip earlier that day. Signal problems caused delays and shortened his layover even further.

BLAME THE WORKER?

Three other recent wrecks—Chatsworth, California (September 12, 2008); Lac-Mégantic, Quebec (July 6, 2013); Spuyten Duyvil, New York (December 1, 2013)—have all been attributed to some form of “operator error.”

But these incidents, like the recent Amtrak one, had another factor in common: the person in the locomotive cab was working alone.

Commercial airliners routinely have copilots: two qualified, certified crew members in the cockpit. Perhaps trains should provide for the same in the cab of a locomotive.

Sometimes it may turn out that the worker did make an error. But simply pointing the finger does little to help us understand what factors might have contributed to the error—fatigue, task overload, crew size reductions, lack of training, distraction—or prevent future wrecks.

Workers are human beings, prone to make mistakes—regardless of how many rules are written up, what discipline is threatened, or how many observation cameras are installed. (See box.) We must take this reality into account, and equip railroad workers with the tools necessary to perform the job safely.

[Ron Kaminkow is a working locomotive engineer and general secretary of the cross-union group Railroad Workers United. Read more at railroadworkersunited.org.]