After this article was published on June 30, some of those quoted in it became concerned about retaliation. Some names have been removed.

Workers organized two protests at Ford Motor Co.'s engine plant in Lima, Ohio, on June 19. One was a picket at shift change made up primarily of Black workers, objecting both to blatant racial insults and to a hierarchy that they allege keeps Black employees from moving up.

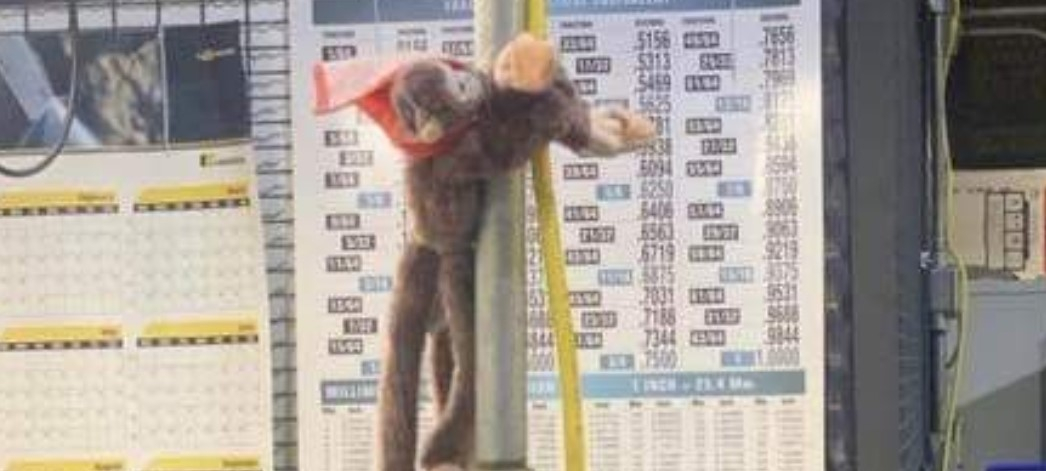

The other was a one-day strike by white workers in the factory's tool room, who boycotted work to protest the firing of a fellow journeyman toolmaker who had hung a stuffed monkey in the work area where it was seen by a Black apprentice.

The monkey incident was only one of a series of insults at the plant in the last few years. Racist graffiti has been scrawled in restrooms. Nooses have been found.

“I am on the civil and human rights committee,” said one Black 10-year employee, “and people come to me with issues weekly. And I have to tell them about our process, the systemically racist process that has proven over and over again that nothing will be done.”

Her daughter is a cheerleader at Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta, a historically Black university. When the 10-year employee wore a Clark shirt to work that said “The Blacker the College the Sweeter the Knowledge,” management called her in, said that someone was offended, and told her to take the shirt off, turn it inside out, or go home without pay. And yet, she says, clothing with MAGA and Confederate flag logos are a daily occurrence.

She believes the plant's atmosphere has deteriorated since Donald Trump was elected. “He openly tweets about his racism and he gets away with it,” she said. “He sets the tone.

“It's not a civil rights violation, it's just degrading.”

NAACP GETS INVOLVED

Pastor Ron Fails, head of the Lima NAACP, joined the Juneteenth protest and had encouraged workers to carry it out. He said the Ford plant had a good track record of hiring Black workers into production jobs, and that Black workers had not always had to endure a racist climate.

“The problem is in supervision and skilled trades,” Fails said. His father, uncle, and cousin all retired from Ford, he said, and the plant used to be seen as “the place of opportunity in both management and skilled trades.

“When unions were strong,” he said, “Black people at Ford Motor Co. did well, but unions now are very weak. The UAW [United Auto Workers] has entered into some kind of partnership with Ford Motor Co. and I don't understand the relationship.

“It's a culture of fear, a very unhealthy culture.”

Lima, a Rust Belt Northwest Ohio city of 38,000 “including two prisons,” Fails said, was about a quarter Black as of the 2010 census; workers estimate the plant to be about a third Black. Of 169 management positions at Lima Engine, three are held by African Americans; of 36 team leaders, an hourly position with slightly higher pay and responsibilities, six are black. Union positions that represent members in the grievance procedure—“committeemen”—are almost all white.

Fails said that when a Black man was hired into the number-two position in management, union chairman Roger Maag sent a text that Fails paraphrased as "we've lost our plant, it's ceased to be a site that promotes from within.

“And this was management hiring management,” Fails said. “Nepotism is high. Because the structure is so weak, people with the wrong intentions can do a whole lot of damage.”

Last year, Fails said, he defended a large number of Black temp-to-hire workers who'd been terminated without justification. The local union had done nothing so Fails dealt with Ford headquarters in Michigan, where officials agreed to reinstate the workers. “Once we brought corporate in and put data on the table, they could see this was not right,” Fails said.

No one from UAW Local 1219 in Lima, Lima Engine management, or Ford corporate headquarters returned repeated calls for comment. The UAW's national Ford Department did return calls but said the International was on vacation for the week. (An update will be added if possible.)

NOT A UNION TOWN

Another Black woman employee transferred to Lima from a Michigan plant four years ago and can't wait for a chance to return home. “I should have investigated this place before I came here,” she said. “This is not a union town at all.” She has read “Go home n****” scrawled in the restroom. She calls the plant culture “a friends and family thing. All I can do is ride it out.”

A Black worker who's been at the plant five-and-a-half years (we'll call him "Smith") said the excuse he's heard for the racism of some white members is that “we have guys from smaller communities that haven't grown up around Black people.” He believes “we do not have a racist membership. We have a few people who have not been dealt with properly and allowed to continue to operate.” The union has had “no positive agenda,” he said, “so negative people have the floor.”

The 10-year employee first applied to be on the union's civil rights committee three years ago but was told “we usually just keep one person”—a committee of one. That one person, according to her, had never done an investigation. After a subsequent incident she was called to the union office and placed on the committee—a case of crossing t's and dotting i's, she thought.

Now, despite being sent to union trainings and holding meetings, she feels that nothing has been done. “It's finally time to get it out publicly,” she said of the protest.

RACISM IN THE TOOL ROOM

The toolmaker apprentice, who declined to talk with Labor Notes, sent a photo of the stuffed monkey to Smith. It was not the first time the apprentice felt he had been racially harassed.

Smith went to the HR department and recommended that the plant manager get out in front of the issue and make a statement about the monkey incident. Management hemmed and hawed, saying they'd need approval from Ford headquarters. Smith and the 10-year employee began planning a rally and some workers met with Fails.

Management then learned of plans for the protest and fired the journeyman toolmaker. An HR staffer known for her problematic behavior was also forced to retire.

Some supervisors told workers in advance not to let the afternoon picket line (which was purely informational) keep them out and warned them that they must come to work in any case. The small rally was covered by the Lima News.

The same day, almost all the white toolmakers took the day off in sympathy with the journeyman. One white toolmaker went to work and then attended the rally. When the strikers returned to work the next Monday, management said not a word to them, according to sources.

The Facebook page of a local news site reported on the rally and then blew up with angry comments from engine plant workers and others.

Black workers are continuing to meet. Both Smith and the 10-year employee are running for union office.

Smith said, “We have an election coming but F an election, F the position, F this job if have to stop being a Black man.”

Hate Strikes in World War II Detroit

Wildcat strikes—walkouts unauthorized by top union leadership—are often celebrated as the supreme expression of rank-and-file militancy. But such militancy hasn't always translated to solidarity.

During World War II, union leaders temporarily sheathed labor’s most potent weapon, agreeing to a no-strike pledge to ensure an uninterrupted flow of armaments for troops overseas. The wartime manufacturing boom drew many thousands of African Americans to northern cities in the second “Great Migration.”

Black workers had largely been relegated—when they were hired at all—to manual labor within factories, but in 1941 the federal government, under pressure from labor and civil rights activists like A. Philip Randolph, banned discriminatory practices in defense production.

In Detroit, where most big plants were by this point represented by the United Auto Workers, a series of “hate strikes” erupted, when groups of white workers objected as African Americans asserted their right to better-paying (and previously whites-only) jobs. These strikes were sometimes led—or at least, not discouraged—by local UAW officials, and were often abetted by racist managers.

Some of these actions were massive; in 1943, 25,000 whites at Packard walked out for a week to protest the promotion of two Black workers.

The UAW was a relatively new and predominantly white organization. But top officials, roundly condemning “vicious race prejudice,” pledged to expel the wildcatters from the union and offered them no protection from company discipline. Government officials in Washington bolstered the UAW’s tough stance by threatening wholesale firings of hate strikers.

In the face of such concerted opposition, racially motivated walkouts in Detroit defense plants virtually disappeared after 1943.

With the World War II hate strikes, rank-and-file defiance equaled divisive racism. It took union leadership to make clear what solidarity really meant.

—Toni Gilpin