Teamsters are up in arms over looming pension cuts that could slash the incomes of both current and future retirees—anyone under 80.

They’re battling trustees of the enormous Central States Pension Fund, which has said that cuts of up to 30 percent may be necessary, as soon as possible, to keep from running out of money. Those trustees represent both management and their international union.

At the same time, worker and retiree activists are also battling corporations bent on eliminating pensions altogether. The latest political blow came in December when Congress passed a bill, in the middle of the night, to allow cuts to certain already-earned pensions.

Bob Amsden drove a truck in Wisconsin for 33 years, over the road and local. He said he got involved because he “couldn’t believe they would do something like this to the people who built this country.

“We don’t contribute to their pockets, so they went after retirees. If they can beat us down, the rest will fall like putty.”

Ten Million Pensioners

The Central States Pension Fund includes 25 states in the South and Midwest, from Florida to North Dakota, covering 65,000 working Teamsters, 180,000 retirees, and 30,000 surviving spouses. Central States was the most active lobbyist for the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014, which made the cuts legal.

Most multiemployer plans are secure, but union members in funds designated “critical and declining” could now see cuts. There are 1,400 multi-employer pension plans in the U.S., with about 10 million participants, including many Teamsters and construction, hotel, and grocery workers.

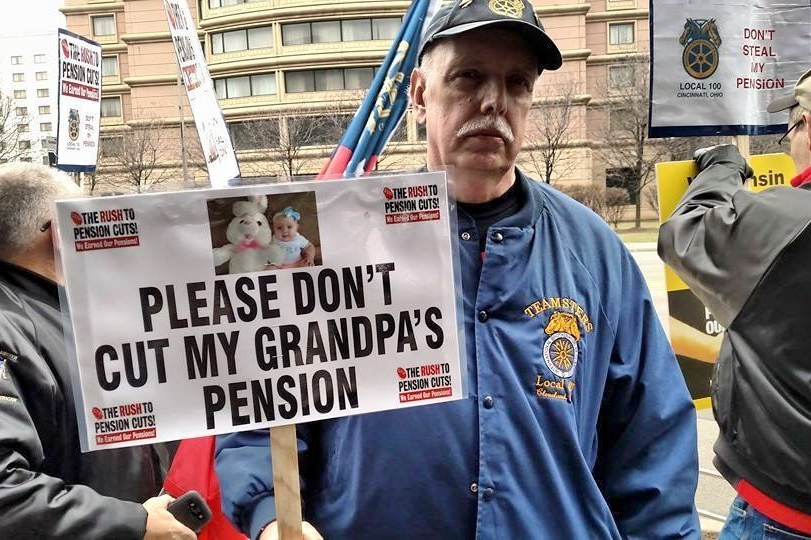

A dozen meetings around the Midwest and South over the last month have attracted 100 to 200 angry members apiece, as activists and local retiree clubs learn their benefits are in danger. The meetings are likely to grow in size and number: Central States has just sent out notices to every member warning that cuts are coming.

Committees have formed in Cleveland, Columbus, the Twin Cities, Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Memphis, and North Carolina. Activists are scheduling meetings with their Congresspeople and writing them letters, leafleting and raising questions at local union meetings and Teamster retiree clubs, and pestering the Teamsters International to do something.

An April 8 rally near Chicago, outside a meeting called by Central States officials to inform Teamster local officers, drew 150 members from eight states, including as far away as Georgia.

Amsden says the average Central States pension is $1,230 a month ($14,760 a year). “You take 30 percent of that away and what will they have to live on?” he asks.

Politicians say they don't want to pay for a “bailout” of the fund, but Amsden predicts, “They are going to bail us out one way or another. People who never expected any government assistance in their life, they’re going to have to go for food stamps.”

For those with decent pensions—some make $36,000 a year—the cuts could be as high as 65 percent, said Mike Walden, a 31-year Roadway driver who founded the northeast Ohio group.

Sue Cole, wife of a retired carhauler and a founder of the Teamsters Local 604 Pension Protection Committee in St. Louis, said, “They act like 30 or 40 percent is no big deal. Our feeling is that we worked for it. They mismanaged it, we didn’t. Why should we lose any portion of our pension?”

CAN THEY DO THAT?

Pensioners have counted on the fact that it was illegal to cut benefits for the already retired, thanks to the 1974 ERISA law. But last December Congress passed the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act—after heavy lobbying by Central States, which became the poster child for troubled pension funds.

The act was tacked onto the “Cromnibus” appropriations bill (which kept certain government functions from shutting down) to avoid debate and so that no Congresspeople had to take clear responsibility for it.

It created a new category of multi-employer pension fund: “critical and declining.” If a fund is projected to run out of money in 15 to 20 years, its trustees now have the right to cut benefits, after a vote of the beneficiaries.

Anti-cuts activists point out that, because the stock market is doing well, the Fund is actually richer now than it was at the end of 2008, after the financial meltdown. It has $18 billion in assets, versus $17.3 billion then. Such gains aren’t likely in the future, but the Fund’s current relative health is reason enough, they say, to slow down and take a look at other possible solutions.

Walden spoke scornfully of Thomas Nyhan, who, he points out, made $662,000 in 2013 as executive director of Central States: “In his letter to people April 8 he said he’s sorry he can’t find an easier solution. I agree, there’s nothing easier than just cutting our pensions. Don’t do anything that might require thinking.”

The committees are gathering petitions demanding that the Fund seek a “second opinion,” an independent audit of its actuarial and financial status.

“We know it’s in trouble and will run out if no steps are taken,” says Ken Paff of Teamsters for a Democratic Union, which is backing the retirees’ movement. “But how did they determine that it has 11 years till it runs out? I used their figures and I got 17. Let the members see behind the curtain.”

The Teamsters pension movement has joined the Pension Rights Center, the AARP, and some unions to support a soon-to-be-introduced bill to delay or repeal the cuts and back up troubled plans.

Congresswoman Gwen Moore of Wisconsin wrote to the committee in her state, “I refuse to force beneficiaries to be singled out as the first to sacrifice in the reform... If you are going to take the extraordinary measure to change long-standing ERISA laws on benefit cuts, then all the reforms need to be made at once so that everyone is putting skin in the game simultaneously.”

STACKED VOTE

Under the law, both retirees and active workers get to vote on any cuts—but a failure to vote counts as a “yes,” and in a big fund like Central States, the Secretary of the Treasury can override a “no” vote and impose the cuts anyway.

The law requires arguments on both sides to appear in the ballot mailing, but with five statements in favor of swallowing the cuts and just one against.

Nonetheless, assuming the Fund opts for draconian cuts, activists will campaign hard for a “no” vote. “We call it social disruption,” Amsden said. “We’re doing a media blitz. We have 11 committees throughout the Midwest; they’re all forming Facebook pages.” In March his group made the front page of Milwaukee’s daily paper.

They expect the Fund to tell members the exact amounts of the proposed cuts this summer, and to hold a vote in early fall. “We’re going to ride the pony till it dies,” Cole said. “We are going to say no because we aren’t guaranteed they won’t come back in another year and ask for more.”

VOTING ON THE PERPS

Pensions will certainly be an issue in the 2016 election for top Teamster officers, as President James Hoffa and his officers back the cuts and challengers Tim Sylvester and Fred Zuckerman blame Hoffa for the decline of the Fund.

In the last officers’ election only 300,000 of the 1.3 million Teamsters voted, with two challengers receiving a combined 41 percent of the vote. So the 65,000 working Central States Teamsters could prove a formidable voting bloc.

The officers sometimes try to have it both ways. At the April 8 Chicago rally against the cuts, International Vice President John Murphy showed up to praise the demonstrators and claim Hoffa was on their side. Meanwhile, inside the Central States meeting, international representatives were telling local officers the cuts were mandatory.

Walden says his many calls to Teamster headquarters have gone unreturned. “As far as transparency and communication, they’re avoiding us,” he said.

The single biggest reason Central States is in trouble is that the international union allowed UPS, by far the largest employer of Teamsters, to leave the fund in 2008. The Fund’s annual income would be about double if 45,000 UPS workers in those states were still members.

But Hoffa let UPS out, in return for the company’s letting him organize 13,000 workers at a new subsidiary, UPS Freight. Those workers now have a union contract—but with an inferior pension.