Workplace Bullying in Higher Education is Rampant. We’re Fighting Back

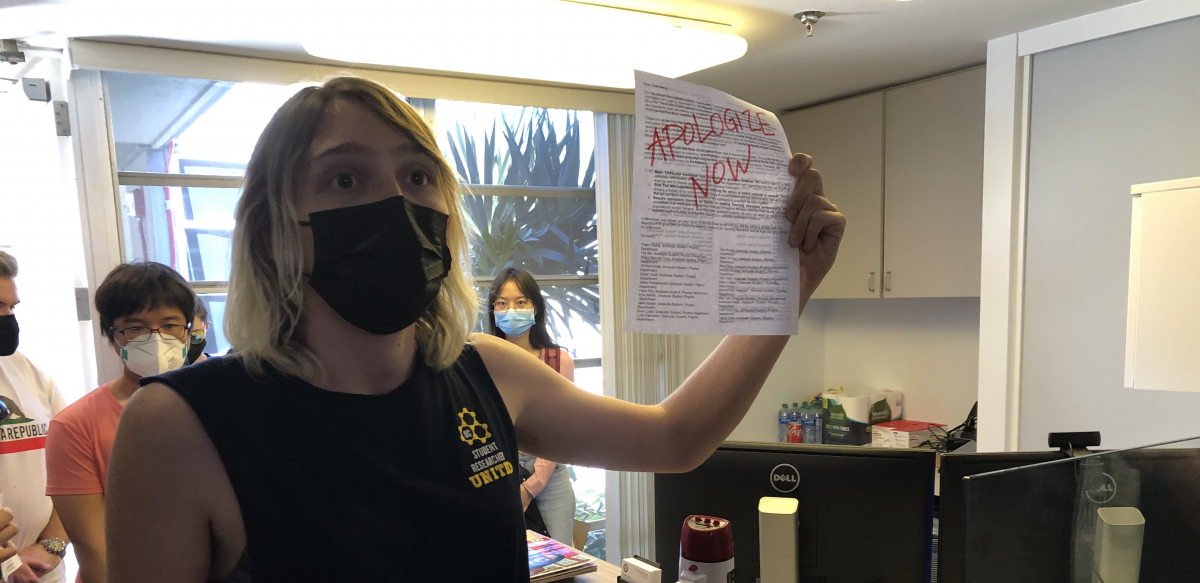

Members of the UAW at the University of California are shining a spotlight on the problem of bullying and abuse in higher education and demanding an end to it. Photo: UAW Local 2865

Grabbing her hair, the boss held scissor blades an inch from her face. “If you don’t give me any brilliant ideas I’m going to cut your hair off,” he deadpanned.

Was this a sick joke? Was he serious? She was alone in his office with him. She was petrified.

You might think this assault happened in some notoriously wretched workplace, the kind of abuse that only occurs in sweatshops halfway across the globe.

But you would be wrong.

This happened to one of us, Liz Adler. Liz was assaulted and threatened by a scissors-wielding professor five years ago in a prestigious laboratory at the University of California San Diego, one of the top research institutions in the country. (Liz is using a pseudonym as she’s still employed at the university where her assailant is a tenured professor.)

You might think this sort of mistreatment is rare in higher education. But again you would be mistaken.

BULLYING IS COMMON

The shameful secret of the academy is that bullying is common in classrooms and research laboratories. Senior faculty and administrators routinely threaten, shame, belittle, and retaliate against graduate teaching assistants, researchers, undergraduates, and others. And it is often reported as a precursor to the harassment and discrimination that has forced so many gifted academics, many of them women and people of color, off their career paths.

In just the last few weeks, as we’ve begun talking with more of our fellow graduate students about our experiences, we’ve heard of colleagues at UC San Diego who were yelled at by faculty, publicly belittled, and even pushed out of a program because of a disability. We’ve seen colleagues recoil in horror as a professor interrupted his physics lecture to tell more than 200 students that the teaching assistants (including the other two co-authors, Yiwen Huang and Marco Man-Ho Tang) the department hired were lazy, stupid, and overpaid. The professor also complained about the teaching assistants to their research advisors, potentially jeopardizing their careers.

We’ve heard international postdoctoral scholars describe how their principal investigator—the professor who hires them—belittled and threatened to fire them. For international scholars, termination doesn’t just mean losing your job; it means being forced out of the country, since the visas of international scholars are tied to specific employment.

CONTROL OVER CAREERS

Unfortunately, these examples are not exceptional, either at the University of California or elsewhere in higher education.

A study last year by researchers from Michigan State University and Wake Forest University found that academic bullying—sustained hostile behavior from one's academic superior—was rampant in higher education, both in the United States and around the globe. Some 84 percent of survey respondents reported experiencing bullying, and 59 percent witnessed abusive supervision. The abuse ranged from ridiculing, threatening and publicly shaming researchers and teaching assistants, to removing funding, falsifying negative review letters, misappropriating credit, and canceling visas or fellowships.

The journal Science last year catalogued harrowing abuse tales from students, researchers, postdocs, and junior faculty: People driven to depression, harassed out of their profession, and brushed off and retaliated against when they dared to complain. University of Wisconsin students held a protest two years ago after a notoriously abusive advisor drove a doctoral candidate to kill himself.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Bullying is rampant in higher education because the abusers know they hold tremendous power over young teachers and budding scientists: they control not only our paychecks, but our career pathways. And for international scientists and scholars, they control the very right to live and work in this country.

NOT ‘A FEW BAD APPLES’

Given that brutal reality, it’s no wonder that researchers found that 71 percent of those targeted by bullies don’t report the incidents. And those who reported the bullying overwhelmingly reported bad outcomes.

This shows that the problem isn’t just “a few bad apples.” Bullying is a prevalent phenomenon in academia, carried out by individuals—mostly, but not all, men—who believe they are above reproach, lording over their little dominions. And it is tolerated and excused by deans, department heads, and university executives who are motivated to turn a blind eye because true accountability would upset relations with powerful faculty and force the institution to reckon with hard truths.

In Liz’s case, the abuser was a tenured biologist, world-renowned for his research and successful at bringing grant money to UC San Diego. He was paid more than $300,000 in 2020. Liz was a PhD student researcher, paid one-tenth of what the professor made, working hard to learn her profession, do good science, and pay the rent every month. Against him, she had no chance.

But the three of us, along with our colleagues throughout the University of California system, are determined to fight back. We’re using our collective voices to expose the endemic problem of bullying in higher education, and we’re applying our union power to demand substantive change. At the 10 UC campuses, postdocs, researchers, teaching assistants, graders, and tutors are among the 100,000 higher education workers across the nation who are united in the UAW.

All of us are bargaining union contracts with the UC this year. There are 48,000 of us together at UC, and together we are insisting that our employer commit to contractual protections against bullying and harassment, such as faster response times for reported instances of bullying, and for bullying complaints to be subject to the union grievance process.

We’re not just bargaining. In March two of us (Yiwen and Marco) joined with union members from other departments to occupy a top administrator’s office. Our disruptive action got results: within days, a top university dean issued an extraordinary apology and directed the offending faculty member to write a letter of contrition to the teaching assistants. That’s just a start to address the toxic department culture, but it’s a powerful demonstration that when we act together we can force the institution to face up to the crisis.

A UNION ISSUE

As union members, we are fighting for a UC in which all of us are free from harassment and discrimination; where we can do world-class science, educate and mentor undergraduates, and have confidence that we will be treated with the respect and dignity that every worker deserves.

The professor’s assault against Liz five years ago was horrific. She overcame the trauma thanks to supportive family and friends, co-workers, and faculty, and was fortunate to be able to transfer to a different program and a different lab, where people are treated with respect.

But we can’t break the culture of bullying and abuse on our own. That’s why we’re excited that as a union we are shining a spotlight on this endemic problem and demanding an end to it.

No one should have to endure what we’ve been through. We hope that by speaking out and telling our stories, other union siblings will feel emboldened to step out of the shadows, join our public call, and unite in action. Working together, we will begin to deconstruct this culture of toxic power dynamics that continually undermines the mission and purpose of higher education.

Yiwen Huang and Marco Man-Ho Tang are teaching assistants in the Physics Department at the University of California at San Diego. Liz Adler is the pseudonym of a former PhD researcher in the Biological Sciences Program at the University of California at San Diego. They authors are members of Auto Workers Local 2865.