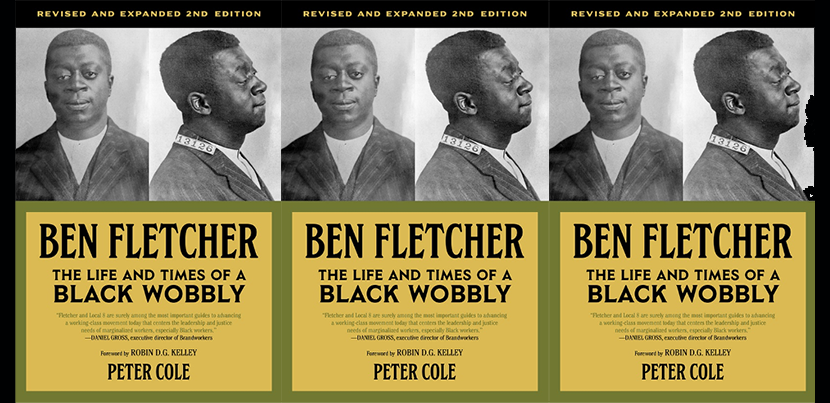

Review: This Little-Known Black Wobbly Dockworker Led the Most Powerful, Democratic Union of His Day

Ben Fletcher agonized over the degrading poverty of Philadelphia's dockworkers. He spent his life working with and organizing them. Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, Second Edition, by Peter Cole, PM Press, 2021

Growing up in Philadelphia, I learned about some of the rich local labor history: the 1827 founding of the first union to cross craft lines, the 1835 general strike, and the 1869 founding of the Knights of Labor. Some of it was personal—my father took part in the 50-day teachers strike of 1981.

But it wasn’t until decades later that I heard about a young Black firebrand named Ben Fletcher who led the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) Local 8 dockworkers union through a tumultuous decade in the early 20th century.

Fletcher remains much lesser known than his African American labor and left contemporaries A. Philip Randolph and W.E.B. Du Bois. Yet Local 8 was perhaps the most powerful union of its day, and the most successful interracial union of its era. It was a model for how workers can run their unions democratically through direct action on the job.

Thankfully Peter Cole has brought Fletcher to renewed attention in a second and expanded edition of Ben Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly. Cole, a history professor at Western Illinois University, has collected an amazing archive of documents that fill out this fascinating story. Here’s how he summarizes Fletcher’s legacy:

“An avowedly revolutionary union led by a black man forced corporations in America’s third-biggest city and fifth-largest port to deal with a union in which the great majority of members were African Americans and European immigrants. And they did it without ever signing a contract, instead enforcing their demands based upon the ever-present threat of a strike.”

I also recommend Cole’s previous Wobblies on the Waterfront: Interracial Unionism in Progressive-Era Philadelphia, about the rise and fall of Local 8. We owe him a lot of gratitude for years of scouring various archives. Cole also discussed Fletcher and Local 8 on a recent podcast.

A DECADE OF DOMINANCE

The book’s introduction gives a brief account of Fletcher’s life and the history of Local 8. Born in 1890, Fletcher grew up near the Delaware River docks where he eventually worked. At that time dockworkers were hired by the “shape-up” system: you lined up and hoped to get chosen for the day’s work.

Fletcher joined the IWW around 1910 and became a leader of the new Local 8 in 1913. The local was born after a successful two-week strike by the 4,000 dockworkers, who opted to affiliate with the IWW rather than the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA)—foreshadowing a decade of conflict between the two unions and their philosophies of unionism. Perhaps Local 8’s greatest victory was abolishing the shape-up and establishing the hiring hall, where the union would dispatch the workers needed each day.

Local 8 was an incredibly diverse union: one-third African Americans, one-third Irish and Irish Americans, and one-third other European immigrants. It made real the IWW’s commitment to interracial unionism, which was extremely rare for unions of that era. The IWW argued that employers kept Black and white workers fighting each other, using race and racism to hurt all workers.

Fletcher also joined the Socialist Party, but his politics were pulled toward radical unionism rather than electoral work. In a letter to a friend he wrote, “While I do not countenance against the working class striking at the ballot box, I am firmly convinced that foremost and historical mission of Labor is to organize as a class, Industrially.” Cole writes that Fletcher “was resolute that the path away from capitalism to socialism was via worker power, on the job, in industrial unions that eventually would pull off a mammoth General Strike to seize power from capitalists.”

Cole describes the classic Wobbly (the nickname for IWW members) style of organizing through direct action on the job. Using work stoppages and other tactics, Local 8 workers fought to control the jobsite as much as possible. For example, if the bosses hired non-members or fired any Wobblies, workers stopped work, delaying the loading or unloading of ships that were on a tight schedule. Through countless day-to-day actions like this, the IWW strengthened its presence on the docks, and improved wages and working conditions, without ever signing a contract.

The local also abolished the racially segregated work gangs that bosses previously had used to pit workers against each other in competition. All work processes, along with all union committees and events, were racially integrated. “Where it had the power,” Cole writes, “the IWW ended segregation—without a legal contract, without an electoral campaign, and with zero influence among local or national politicians.”

THE ILA EDGES IN

Fletcher was caught up in the government’s repression of the IWW when World War I started; he and many other Wobblies were arrested. The government called the union “a vicious, treasonable, and criminal conspiracy” and sought to destroy it. Fletcher, the only Black defendant, served several years in prison, returning to Philadelphia to organize again with Local 8.

However, by the mid-1920s, the ILA emerged as the dominant union on the docks. The ILA was favored by the bosses, and its top-down approach to unionism gave it stability and a steady relationship with employers—but working conditions and democracy on the docks suffered. The employers were willing to sign a contract with the ILA that included the eight-hour day, in return for subservience and labor peace. As Cole describes it,

For the first time, the Philadelphia longshoremen had an ironclad legal agreement with their employers. This contract, unfortunately, ensured that workers earned lower wages than in the open shop era while sacrificing their right to strike at will, which the IWW considered essential to maintaining and expanding worker power. Further, their autonomy declined dramatically once the bureaucratic and hierarchical prerogatives of the ILA were substituted for the democratic traditions of Local 8. Within a few years, regular meetings and contested elections were distant memories. By 1930, New York–style ILA corruption was rampant.

Fletcher continued to organize for years, becoming widely known in labor and left circles. Tragically, a stroke in 1933 and poor health thereafter ended his activism until his death in 1949.

This was a tremendous loss. Cole wonders “what Fletcher might have done in the mid-1930s when, sparked by a Great Depression that seemed to prove the failures and contradictions of capitalism, a massive surge in unionism and antifascism occurred?” Fletcher lived his last years in New York City and was buried in Brooklyn in an unmarked grave that has never been located.

FLETCHER THE ORGANIZER

The second, longer part of the book is a great collection of articles and reports by and about Fletcher and Local 8. They deal with organizing campaigns, strikes, and other events in the life of the IWW. There are government documents from the investigations of Fletcher, including his prison correspondence. Helpfully, Cole provides historical context for all these materials.

Fletcher was widely regarded as a powerful speaker. One letter about his speaking tour in the 1920s reports that at “several meetings about fifteen hundred have listened, spellbound…” and that he “in thunderous tones with clarion ring so capably espouses labor’s cause.” In another letter, an AFL official says Fletcher was the “only one I ever heard who cut right through to the bone of capitalist pretensions, to being an everlasting ruling class, with a concrete constructive working class union argument.”

A fascinating article from the Black socialist magazine The Messenger reports on a Local 8 meeting where both Black and white workers rejected the idea of forming separate locals:

“It is interesting to note, in this connection, that the white workers were as violent as the Negroes in condemning this idea of segregation. All over the hall murmurs were heard, ‘I’ll be damned if I’ll stand for anybody to break up this organization,’ ‘It’s the bosses trying to divide us,’ ‘We’ve been together this long and we will be together on.’”

An article by Fletcher implored unions to organize Black workers: “No genuine attempt by Organized Labor to wrest any worthwhile and lasting concessions from the Employing Class can succeed as long as Organized Labor for the most part is indifferent and in opposition to the fate of Negro Labor.” He also long insisted that Black workers organize with whites and not form their own segregated unions.

In a tribute to Fletcher after his death, a colleague remembered visiting him in Philadelphia: “Day after day and night after night he covered the water front, twenty miles of it, repeatedly at the risk of his life. He took me to see the slums in the City of Brotherly Love where longshoremen and their families lived. He agonized over their degrading poverty. He was of them. He was with them.”

FLETCHER’S LEGACY

Historian Robin D.G. Kelley, in the book’s foreword, describes Fletcher as a “radical pragmatist in that he paid attention to context, emphasized solidarity, and approached the work in an improvisatory and flexible manner—all without ever losing sight of the long-term goal: the emancipation of the working class from Capital.”

Ultimately Local 8 couldn’t survive against the combined assault from the government, longshore employers, and the ILA. But Fletcher and his local blazed a path of militant unionism a century ago that has much to teach us today.

I’m glad Cole included a story by Anatole Dolgoff, one of the few people alive who knew Fletcher. I met Dolgoff several years ago when he published Left of the Left a memoir of his anarchist father Sam. He has several chapters about Fletcher, and recounts meeting him at the old New York City IWW hall in the 1940s. He remembers that Fletcher “appeared an old man whose health was shot when I knew him.” He says that Fletcher “projected good humor and decency—you wanted to be in his company—but there was something sad that seeped through.”

Ben Fletcher—the forgotten legend, the former giant. With decades of militant organizing experience, and still only in his 50s, he was no longer in the action. The labor movement needed him then, and we need more folks like him now.

Eric Dirnbach is a labor movement researcher and activist in New York City. He has published in Jacobin, New Labor Forum, Organizing Work, and Waging Nonviolence.