A Common Defense: Mobilizing Veterans in Labor to Beat Trump and the GOP

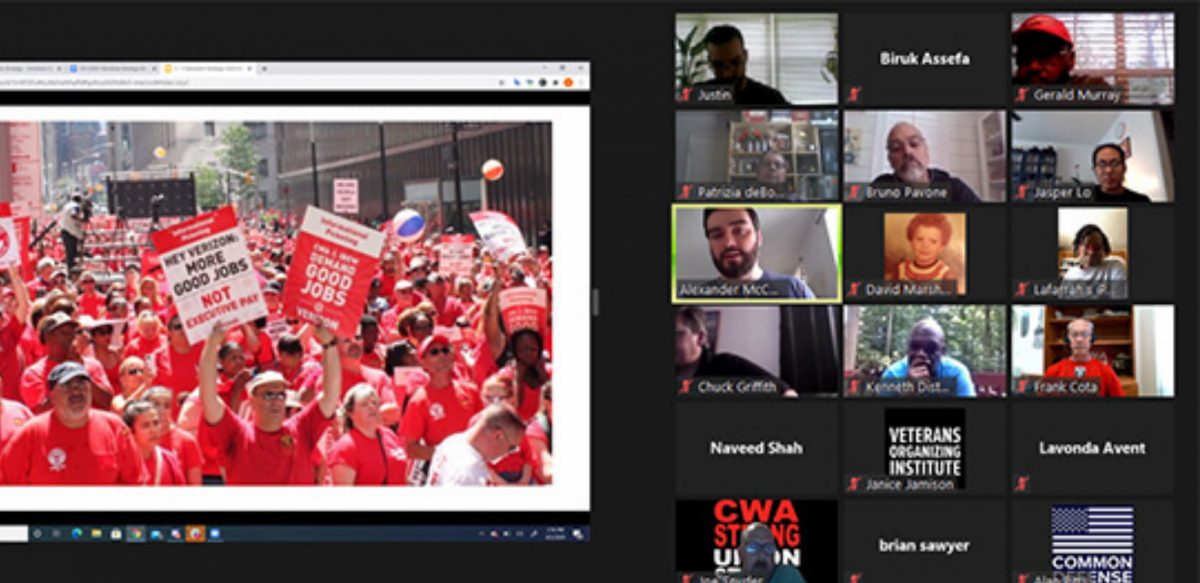

Last month 14 military veterans completed the Communications Workers' first-ever Veterans for Social Change Training Institute, where the curriculum included skills useful in electoral campaigning. The union is trying to help prevent the GOP from out-organizing the Democratic Party among veterans and military families.

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump dissed a Gold Star family that had lost a son in Iraq. He called Senator John McCain, America’s most famous prisoner of war, a “loser” for being captured in Vietnam. When asked about widespread sexual assault in today’s military, he dismissed it as a problem. He had to be publicly shamed into making a promised donation to veterans’ charities.

His opponent, Hillary Clinton, was backed by more than 100 former high-ranking officers. Trump was endorsed by only a few. Nevertheless, on election day four years ago, most military veterans ending up voting for a wealthy recipient of five draft deferments. Among former military personnel, Trump beat Clinton by a 26-point margin, a bigger percentage of the “vet vote” than McCain’s own share when he ran against Barack Obama in 2008.

A Pew Poll conducted in the fall of 2019 showed that Trump remained popular among veterans, even as his ratings began to sink among other constituencies. U.S. military intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan—which Trump criticized as a candidate in 2016 and, again at West Point this year—is now viewed unfavorably by a majority of the vets surveyed. In blue-collar communities in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin which suffered some of the highest post-9/11 combat-casualty rates, veterans and their neighbors helped Trump carry those decisive swing states four years ago.

To repeat that regional sweep in 2020 and give Trump a second term, the Republican Party has once again targeted the nation’s 20 million veterans as a key voting bloc. Among those trying to prevent the GOP from out-organizing the Democratic Party among veterans and military families were the Communications Workers (CWA) and Common Defense, a national organization of progressive veterans.

CWA and Common Defense unveiled their joint initiative last fall, when CWA President Chris Shelton, an Air Force veteran and former telephone worker, announced that his union was creating a “Veterans for Social Change” program. Its purpose is to “develop and organize a broad base of CWA activists who are veterans and/or currently serving in the military.” As the union notes, veterans, active-duty service members, and military families “are constantly exploited by politicians and others who seek to loot our economy, attack our communities, and divide our nation with racism and bigotry so they can consolidate more power amongst themselves.” CWA seeks to counter these Trump-era threats by encouraging veterans in its own ranks to engage in grassroots campaigns with community allies and increase awareness of veterans’ issues within CWA, like the need for a strong fully funded veterans’ health care system.

Last October, CWA local leaders who served in the military joined veterans from around the country at a Common Defense-sponsored Veterans Organizing Institute (VOI). Previous weekend sessions of the VOI had helped train a network of hundreds of younger veterans to organize more effectively in their own communities, counter the influence of big money in politics, and make politicians more accountable to poor and working-class people. At the training conference attended by CWA members, union activists from swing states like Ohio, Arizona, North Carolina, and Texas shared organizing experiences and learned new skills useful in electoral campaigning and day-to-day advocacy for fellow workers and veterans.

VETERANS ORGANIZATIONS, OLD AND NEW

“The VOI provides a great introduction to getting a grassroots movement started and getting veterans, labor, and the community all working together,” says Brick, New Jersey, Electrical Workers (IBEW) member John Blake, who attended the training. Blake chairs the veterans’ committee of the Monmouth and Ocean Counties Central Labor Council and a similar group within his own Local 400, which represents construction electricians. On the organization chart of the AFL-CIO, its national affiliates, and local CLCs, the dual identity of union members who served in the military has long been acknowledged via the existence of such bodies. But their level of activity may be low unless an activist like Blake takes the lead in “making our union brand more appealing to vets coming out of the service,” which Local 400 does by participating in local events like “Operation Ruck It,” an annual fundraising walk to raise awareness about veteran suicide.

Former military personnel are most heavily represented in the Government Employees (AFGE) and Postal Workers (APWU), where they have a strong collective identity and internal union presence. On an individual basis, union members who are veterans may also belong to local posts of the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, or AMVETS. But these old-line groups tend to be conservative on military and foreign policy issues and not much engaged with issues affecting veterans as workers. Common Defense, in contrast, proclaims its commitment to “progressive values” and seeks partnerships with like-minded unions working for social and economic justice.

Last year, Will Attig, who heads the AFL-CIO’s Union Veterans Council, invited both Common Defense and VoteVets, an advocacy group more closely aligned with the Democratic Party, to discuss their work at a meeting of national union political directors. Attig is a combat veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who joined a southern Illinois local of the Plumbers and Pipefitters after he left the military. He did legislative/political work for his own union and then the Illinois state fed before moving to AFL-CIO headquarters in Washington. After the presentations he helped arrange, both CWA and the IBEW contacted Common Defense about sending members to an upcoming VOI training.

Common Defense grew out of anti-Trump organizing in 2016. Co-founders of the group first met during protests over Trump’s failure to donate money to veterans’ charities, as promised during a campaign event in Iowa. One of the protestors was ex-Marine Alex McCoy, then attending Columbia University on the G.I. Bill. He and a group of like-minded vets “felt really strongly about Trump was constantly using veterans as props while running a campaign that was so founded in hate and division.” During Trump’s first term, Common Defense rallied its 20,000 supporters to call for his impeachment. The group endorsed Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren for president, during the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries, after both worked with its members to get more Congressional signers of a pledge to end “forever wars” in the Middle East.

One particular target of Common Defense lobbying is military veterans now serving on Capitol Hill after midterm election victories that gave Democrats control of the House in 2018.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Veterans Organizing Institute trainings, conducted by Common Defense staff members like McCoy, are designed to hone the political skills of veterans involved in unions, community organizations, and electoral campaigns. Four months after his VOI training, Frank J. Cota, a Marine Corps veteran and vice-president of CWA Local 7026 in Tucson, was in Washington, D.C., as part of a group of CWA veterans urging Congress to pass the PRO Act, legislation that would strengthen private sector organizing and bargaining rights. McCoy believes that Common Defense can play a key support role in workplace organizing, particularly at firms like Amazon and Walmart which brand themselves as “veteran-friendly” and hire tens of thousands of former military personnel while pursuing “anti-worker policies” which often violate federal labor law.

AGAINST VA PRIVATIZATION

Another labor alumnus of the VOI is Army veteran Skip Delano, who returned from Vietnam to become a unionized postal worker, coal miner, and high school teacher. Delano has worked with Common Defense and Veterans for Peace on efforts to support AFGE members at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in their fight against out-sourcing of veterans’ health care by the Trump administration. This community-labor campaign against VA privatization also involves VA nurses who belong to National Nurses United. The NNU is not only trying to save its own members’ jobs and improve the quality of VA services; it also wants to preserve the nation’s largest public hospital system as an important working model of single-payer care.

Based on his own experience as a VA patient, Delano agrees that “the private sector health care system does not have the capability or the capacity to meet the needs of veterans. They will be sent to providers who may know little or nothing about their special problems and may fail to diagnose critical conditions like PTSD, Agent Orange, burn-pit exposure, or military sexual trauma, to name only a few.” Now a union retiree, Delano has decades of experience with good job-based medical coverage. Nevertheless, he believes that “private sector care will be less veteran-centric, of lower quality, require longer wait times, and end up with many veterans getting lost in the system because of poor care coordination and lack of accountability.”

Delano spends a lot of time reminding other veterans about their need to be strong allies of VA caregivers, a third of whom served in the military themselves. He has encouraged veteran participation in “Save Our VA” lobbying activity in Washington, DC and local public forums and informational picketing by patients and providers at VA medical centers. Under Trump, the Republicans in Congress, along with some Democrats, have tried to strip VA staff of the workplace rights and protections they need to act as patient advocates and foes of privatization. “Without that collective voice, doctors, nurses, and other health care professional will have far less ability to speak out on behalf of veterans,” Delano warns.

To keep Trump from getting reelected and doing further damage to federal employee unions and veterans’ health care, Common Defense intervened in multiple election-year controversies over other issues. As COVID-19 infections spread within the ranks of active-duty military personnel, Afghan war veteran Perry O’Brien blasted the Trump administration for putting all Americans at greater risk by dismantling the federal government’s pandemic response team, cutting the budgets of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other public health agencies, and, in the early months of 2020, “downplaying the severity of the crisis.”

FOR RACIAL JUSTICE

When nationwide protests developed last June, after the Minneapolis police killing of George Floyd, Common Defense leaders vigorously opposed military deployments in Washington, D.C., and other cities. Kyle Bibby, a former Marine Corps infantry officer and graduate of Annapolis, urged fellow veterans to stand against “Trump’s authoritarian plan to use the military as his personal storm troopers to suppress dissent.” A co-founder of the Black Veterans Project, Bibby condemned the “use of force by uniformed police and a culture of violence that seeks to dominate communities rather than serve and heal them.” Recalling his own past interactions with law enforcement, in and out of uniform, Bibby declared that “the police don’t care that I’ve gone to war to protect this country—I could be the next George Floyd solely due to the color of my skin.”

Common Defense activists, including Bibby, launched a new campaign, called “No War on Our Streets,” against police department use of $7 billion worth of hardware obtained from the Pentagon. “It was our equipment first,” says Bibby, who served in Afghanistan. “We understand it better than the police do … It’s important that we have veterans ready to stand up and say: ‘These weapons need to go.’” (For more information on this and other CD projects, see here.) When the Trump administration filled the streets of Portland with heavily armed federal agents, Common Defense began working with local veterans there. Among them is a now nationally known Naval Academy graduate named Chris David, who was pepper sprayed and beaten in an unprovoked assault viewed 7 million times on YouTube. In solidarity with David and other peaceful protestors, a “Wall of Vets,” including some active and retired union members, joined the nightly demonstrations against militarized policing.

By mid-summer, with the presidential election still three months away, the efforts of veterans’ organizations allied with labor, like Common Defense and VoteVets, appeared to be paying off. Not only was the Republican incumbent in the White House faring poorly in presidential preference polls conducted among all likely voters, but Donald Trump’s stock was also dropping among those who had helped him gain office in 2016. About half of all active-duty military personnel surveyed by the Military Times had developed an unfavorable view of the president, opposed to just 37 percent when he was first elected. Among officers, his disapproval rating was even higher. Meanwhile, Black Lives Matter protests resonated among the 40 percent of all active-duty military personnel who are people of color—and Trump’s denigration of that movement and his defense of military bases named after Confederate generals definitely did not.

Progressives wooing the “vet vote” saw a similar shift in political sentiment in veteran circles. As November 3 neared, the Biden campaign was clearly making inroads among post-9/11 veterans who are younger, female, and nonwhite, while ex-soldiers who are older white males living in longtime Republican strongholds remained a harder bloc to crack. With a pandemic still raging, the economy cratering, and millions of workers, including veterans, finding their jobs, unions, or health care at risk, there were many reasons for voters who served in the military to choose a new commander in chief.

Steve Early has been a rank-and-file member or national staffer of the Communications Workers of America for 40 years. Suzanne Gordon is also a CWA member via the NewsGuild. She is the author, most recently, of Wounds of War: How the VA Delivers Health, Healing, and Hope to the Nation’s Veterans. They are collaborating on a book for Duke University Press about veterans’ affairs. They can be reached at Lsupport[at]aol[dot]com.

This article first appeared in the journal Social Policy.