Maine Shipbuilders Bring the Hammer Down, Reject Concessions

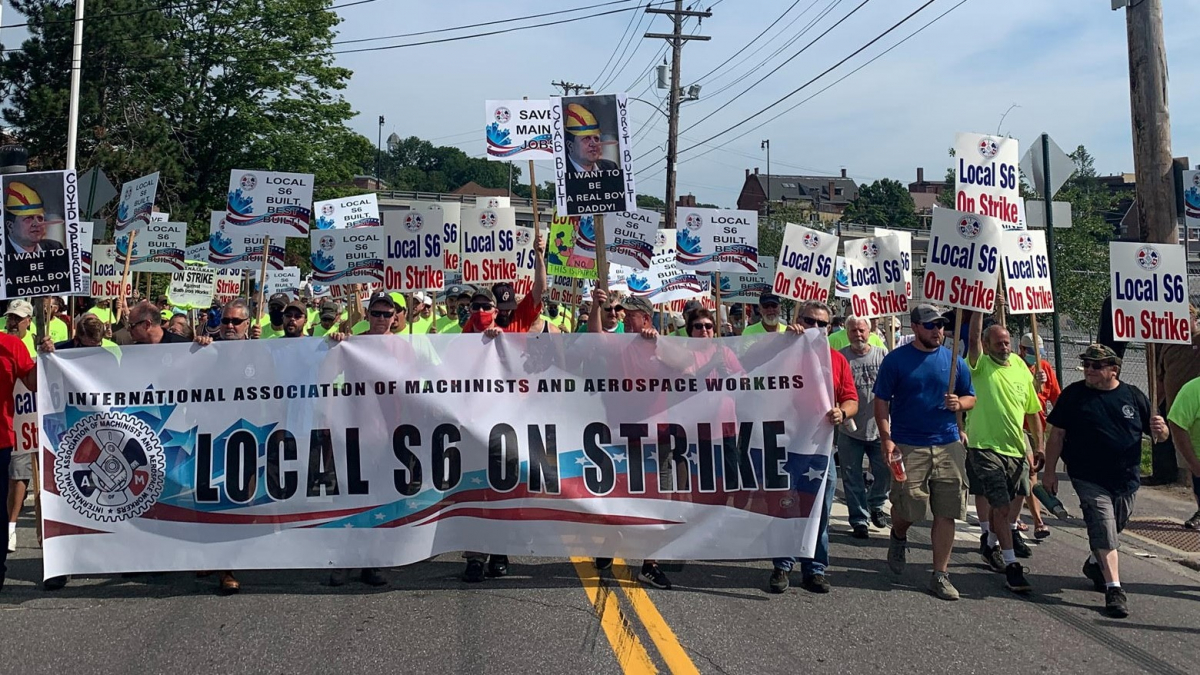

Shipyard workers in Bath, Maine, beat back concessions in a seven-week strike. The company president hailed from a union-busting family. Photo: Machinists

More than 4,300 shipbuilders at the Bath Iron Works shipyard in Maine struck for seven weeks from June to August in the largest private sector strike in the U.S. this year. On August 7 Machinists Local S6 reached a tentative agreement with BIW that keeps existing subcontracting language and protects seniority.

The company’s attempt to gut seniority, such as for overtime and changing shifts, and to massively increase subcontracting was the primary reason 87 percent of members rejected a previous offer. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they will receive the contract in the mail and vote online and via phone, with results expected in late August.

“What we were able to accomplish at the negotiating table is a testament to the strength and solidarity of our membership,” said Local S6 President Chris Wiers.

It wasn’t assured that the members would vote to strike in such a difficult economic climate. In previous years, BIW had pressured workers to accept concessionary contracts that froze wages and eroded job quality, ostensibly to stay competitive on bids for lucrative Navy and Coast Guard contracts.

Last time around, in 2015, workers voted narrowly to give up scheduled raises in favor of one-time bonuses, in order to help the company win a contract to build patrol boats for the Coast Guard. Ultimately, BIW failed to win that contract—despite the concessions.

But on June 13, when BIW made a “last, best, and final offer,” the bargaining team knew it could not accept such a rotten deal, and recommended that members vote it down.

RAKING IN PROFITS

Virginia-based General Dynamics, which bought the shipyard in 1995, is the fifth-largest U.S. defense contractor; it ranks number 83 on this year’s Fortune 500 list. In 2019, it raked in $3.5 billion in profits.

The company’s demands were especially egregious given that last year the Maine legislature granted BIW a $45 million tax break. Already the Trump tax cuts had reduced General Dynamics’ effective tax rate from 28.6 percent down to 17.8 percent in 2018.

Those tax cuts allowed General Dynamics to increase stock buybacks and dividend payments. In 2018 it gave nearly $2.9 billion to stockholders.

General Dynamics also has a long history of anti-union activity, including an attempt to permanently replace 4,000 striking Machinists at its Convair Division facility in San Diego in 1987. Last year, the company settled charges with the Communications Workers that its technology division engaged in unlawful union-busting and failed to pay overtime at its call centers.

A 12-SHIP BACKLOG

Local S6 member Jami Bellefleur said she knew it wasn’t right for workers to sacrifice because of the company's gross mismanagement of the yard.

In April, BIW lost out on a $5.5 billion contract to build Navy frigates to the smaller Marinette Marine shipyard in Wisconsin. Union officials pointed out that the rival shipyard had submitted a superior design and was in a better position to begin work on the ships, as BIW already had a 12-ship backlog of the DDG-51 class destroyer.

However, Bellefleur, a 34-year-old painter, worried that some of the younger members might be lured by the company’s offer of a $1,200 signing bonus and 3 percent annual raises over the life of the three-year contract.

“After the last contract they hired so many new people and they weren’t informed on what was going on and what they were voting on,” said Bellefleur, who comes from a shipbuilding family. “So we tried to reach as many new people as we could.”

BEST BUILT

Located 35 miles north of Portland where the Kennebec River runs into the Gulf of Maine, Bath Iron Works has built more than 425 naval and commercial ships since its founding in 1884. In World War II the shipyard was famous for its Liberty ships, including one of two that are still operational, the S.S. John W. Brown, named after a BIW joiner who organized the first local of the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America at the shipyard in 1935. A sign in front of the yard says “Bath Built Is Best Built”—a reference to praise from Navy officials during World War II.

Bath also has a proud history of collective struggle. Its shipbuilders are believed to have formed the first union in Maine, way back in the 1830s. According to Maine labor historian Charlie Scontras, shipyard workers in Bath also led the state’s first general strike in 1847, bringing all the shipyards in the city to a standstill to demand a 10-hour day. Generations of Bath shipbuilders have used periodic strikes to make BIW a desirable place to work.

But union-busting is a family tradition for BIW President Dirk Lesko. His father Newland Lesko, a former executive at International Paper, oversaw the firing and permanent replacement of striking papermakers in Jay, Maine, in 1987. During the strike, the younger Lesko enlisted scab recruiters in Alabama and Mississippi to hire hundreds of strikebreakers to take jobs in the yard.

The “Bath Built Is Best Built” sign disappeared shortly after the strike began.

THE HAMMER-DOWN

Bellefleur had heard that right before the union’s last strike—55 days in 2000—workers hammered pieces of scrap metal to show their displeasure. She thought a similar action could help raise awareness about the bad contract offer.

“I decided to post about the idea on social media and said ‘let’s start bringing the hammer down to show our solidarity,’” she said. “I wanted to show the company that we recognize what they are trying to do to us and we were not going to stand for it.”

The hammering first started at a satellite BIW shop and then spread to the main yard on June 4. Every hour on the hour, workers grabbed scrap steel from the dumpsters and began hammering away. As cacophony filled the air, managers frantically tried to quell the protest; they started pulling workers into the office without union representation and threatening to fire them.

“They really tried to intimidate the mechanics, especially the younger ones. They tried to squash it as quickly as they could, but that just made it worse,” said sandblaster Tim Suitter. “Everybody joined in and they just wouldn’t stop. They couldn’t walk everybody out fast enough.”

Soon the office was overflowing, so managers had to set up a large tent in the yard to place the unruly shipbuilders; workers dubbed it “the Big Top.” On the first day, more than 100 workers were corralled into the Big Top and about 20 of them, including Bellefleur, were walked out of the yard and suspended.

When news of the action reached union leaders, the bargaining team left the table and came out to the yard to support the workers. Eventually, the team returned to the table and with the help of the union’s lawyer the company agreed to reinstate Bellefleur and the others with back pay.

From then on, the hammering continued every hour on the hour until June 19, when voting on the contract offer started. On June 21 the union announced that 87 percent of members had voted to reject. At midnight, second-shift members walked out the gate and hit the picket lines.

“I really do think the hammer-down kind of unified everybody and got people asking more questions and trying to figure out what we were voting on,” said Bellefleur.

Strikers were joined on the picket lines by Firefighters, Ironworkers, state employees, postal workers, electricians (IBEW), papermakers, stage employees, workers from the neighboring Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, and many others.

IN IT FOR THE LONG HAUL

The company cut off the shipbuilders’ health insurance in the midst of the strike, forcing them to scramble to find coverage elsewhere. Nevertheless, workers stayed out for the long haul.

For John Portela, a 46-year veteran sandblaster, this was his fourth strike. He tells younger workers that being an S6 member means there is always going to be struggle and sacrifice, but it is critical to protect jobs for future generations of shipbuilders.

“As Frederick Douglass said, ‘Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will,’” said Portela. “We don’t gain because of the generosity of the company, we gain because of the demands that we make of the company. There is no progress without the struggle.”

Andy O’Brien is the Maine AFL-CIO communications director.