World War II: When the Government Protected All Essential Workers

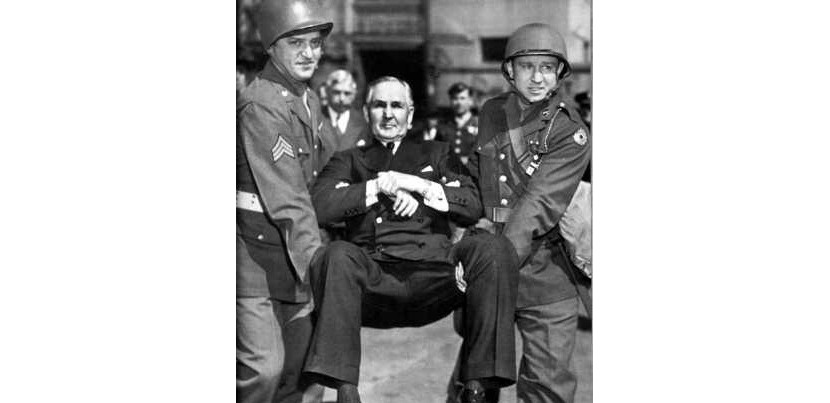

Soldiers removed the CEO of Montgomery Ward when he defied the government's orders to recognize his workers' union and FDR seized the company. Photo: Harry Hall, AP.

Strikes, work stoppages, and protests this week at Amazon, Instacart, Whole Foods, and other workplaces may not have done much to shut down the nation’s stores and warehouses, but they sent America a very loud and potent message none the less.

The thousands of men and women who pick and pack at hundreds of giant fulfillment centers, the millions who stand behind retail counters, and the legion of gig workers tasked with delivering food and medicine to your doorstep now stand at the vital heart of the world’s largest economy.

The fact that such work is now dangerous, that these low-wage workers are “first responders,” highlights the social and economic indispensability, as well as the insecurity and impoverishment, of this multimillion segment of the American working class.

If coal miners, mill hands, and auto workers once stood at the iconic heart of our 20th century industrial imagination, this crisis has finally, but decisively, put those who staff the nation’s retail/distribution complex in their stead. East Asia is now the “workshop of the world,” so world capitalism, and most certainly that in North American and Europe, could not run without a series of global supply chains. The connective tissue consists of all those seamen, longshore workers, truck drivers, distribution center workers, retail clerks, and delivery workers whose labor power holds it all together.

And yet they are getting the short end of the stick. For most pay is low, hours are erratic, benefits are skimpy, turnover is rapid, and in a further insult, the wizards of Silicon Valley have constructed a set of apps and legal scams designed to force millions into a spurious world of “independent contracting.” Except for some grocery chains, most retail/distribution employers—from Sam Walton to Jeff Bezos—are militantly anti-union.

It’s time for workers to organize and the government to protect their right to do so, at the same time that it mandates the safety protocols demanded by this pandemic.

WAR LABOR BOARD PROTECTED WORKER RIGHTS

It happened before, in World War II, another crisis that highlighted the centrality of once marginalized workers now recognized as essential to the larger national purpose.

During the war a higher proportion of Americans worked in factories than at any other time in history. But they had to eat, dress, and buy household goods. So grocery stores, gas stations, warehouses, and retail outlets were all deemed part of the war economy. The Office of Price Administration rationed—and set the price of—meat, candy, tires, and gasoline; dressmakers were required to limit their use of fabric; and the government determined when and if consumer goods manufacturers could get back in business.

Sewell Avery hated all of this. In 1944 he was the 70-year-old autocrat who ran Montgomery Ward, one of the great catalog sales and retail store empires headquartered in Chicago.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Avery was violently hostile to President Franklin Roosevelt, to the New Deal, and to the unions that were trying to organize his warehouses and stores. His lawyers argued that wartime regulations, including protections for the right to organize, should not apply to the civilian goods Montgomery Ward distributed across the country. But the work clothes, auto parts, and farm equipment the company shipped were deemed essential war goods by both the New Dealers and the dollar-a-year corporate executives who ran the wartime mobilization agencies.

The showdown came in April 1944, when Avery refused to comply with yet another order of the National War Labor Board mandating that his company fully recognize the United Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. The union went on strike and FDR promptly seized the company.

A FAMOUS PHOTO

Avery’s stubbornness soon became world-famous when Life magazine captured one of the most striking images of the World War II home front: two soldiers, in full battle dress, carrying a well-suited Sewell Avery out of his headquarters and onto the street. Attorney General Frances Biddle was on hand, to whom the Ward executive yelled, “To hell with the government, you…New Dealer.”

The photo was a sensation because to Avery’s like-minded business associates, it demonstrated just how powerful the wartime New Deal had become. To unionists and other workers, it seemed to assert that the power of a militarized federal government could be enlisted on their behalf.

Donald Trump is in the White House, but in our own moment of national peril, we again need a powerful, progressive state to stand with those on the front lines. The federal government’s failure will undoubtedly be responsible for many unnecessary deaths in the supply chain. Meanwhile, state and city governments, no matter how well led, simply lack the power and resources to insure that workplaces in their jurisdictions are safe.

Jeff Bezos has far more public relations savvy than a Sewell Avery, likewise executives at Instacart, Grub Hub, Walmart, Uber, and other service sector employers. A direct confrontation with the government, state or federal, seems unlikely. But these firms are just as recalcitrant as the Montgomery Ward chieftain. To weather the pandemic, executives at these firms have grudgingly conceded as little as possible when it comes to sick leave, safety standards, and worker voice. They want to get back to an autocratic normality once it is all over.

Our job, following the lead of this week’s heroic supply chain strikers, is to make sure we construct a new order post-pandemic, one where workers are valued and have the power to protect themselves.

Nelson Lichtenstein teaches history at the University of California, Santa Barbara where he directs the Center for the Study of Work, Labor, and Democracy.