Can I Get Fired for Talking about Virus Risks?

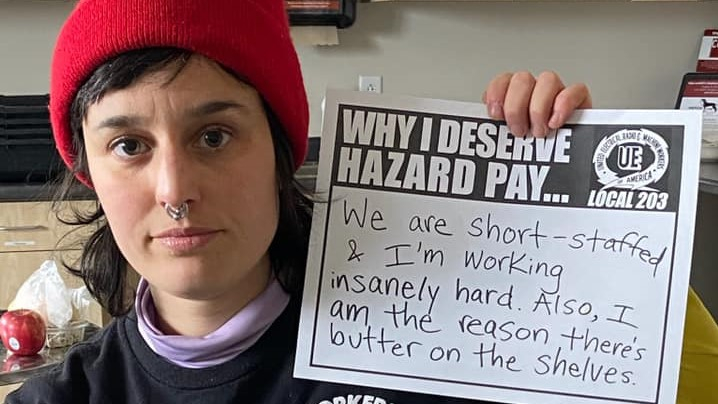

Your employer may not want you speaking out about your pay and working conditions, but you have a right to do it anyway. These grocery workers won a temporary $3-an-hour raise, effective through May 2. Photo: UE Local 203

Many workers still on the job during this pandemic are upset about their working conditions. But can you get in trouble for talking about your concerns—to your co-workers, on social media, or to the newspaper?

In a word: no. Not legally, anyway.

Below is a short run-down of your legal right to organize around wages, hours, and working conditions, even if you don’t have a union—and if you do have a union, your additional protection under your contract.

Let’s be real—employers have been known to break laws and contracts, and the bureaucratic remedies (court cases, grievances) are slow. But often threats are just meant to silence you. Showing that you know your rights may be enough to get management to back off its threats.

Stronger than the law is your strength in numbers. Depending how understaffed your facility is, maybe the bosses could get by if they fired one person—but they certainly can’t afford to fire a whole group. So organize! Get together with your co-workers (at a six-foot distance) and raise concerns together.

Remember, your employer needs you, especially now. They even labeled you “essential.” Now is a time when workers can talk and act more boldly than usual.

Public pressure helps too. A hospital in Washington state recently fired an Emergency Department doctor for raising safety concerns—and it made national news. Most employers don’t want that kind of press.

This article covers your basic legal protections; it’s meant to confirm that you’re absolutely within your rights to start organizing with your co-workers. For more on how to put power behind your demands and get results, check out the advice and latest stories from other workplaces on our “Organizing in a Pandemic” page.

WHAT THE LAW SAYS

For most workers, the federal and state labor relations laws guarantee your right to organize with your co-workers to improve your wages, hours, and working conditions. The technical language is “concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.”

National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decisions over the years have established that this includes conversations on social media—and it includes talking to the news media, no matter what your employer’s policies say.

Legally, it’s important that you’re talking about working conditions, not just disparaging the employer. They might get away with firing a worker for saying, “Don’t come to this hospital, it’s unsafe for patients,” or “Don’t buy our product, it might be contagious.” But workers can say, if it’s true, “Conditions at this hospital/store/factory are unsafe for us workers—and for patients/customers/the public too.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Employers are legally forbidden to discipline you, harass you, spy on you, or fire you for exercising your rights to speak or organize. If they break the law, your formal remedy is to file an unfair labor practice charge at the NLRB or, if you’re a public employee, at your state labor relations board.

The NRLB covers postal workers (yes, despite the Postal Service’s bluster about not talking to the press!) and most private sector workers, union and nonunion. It does not cover agricultural workers, domestic workers, independent contractors, or supervisors. Airline and railroad workers are covered instead by the National Mediation Board.

JUST CAUSE

If you have a union contract, you almost certainly have a second layer of protection: a provision in your contract requiring “just cause” for discipline, meaning you can’t be warned, suspended, or fired without a justifiable reason.

What counts as just cause has been established through arbitrators’ decisions over the years; you can find a good run-down in this article by labor attorney Robert Schwartz.

Bottom line: an arbitrator is not going to say it’s OK to discipline you for talking with co-workers or the news media about how your employer is not keeping workers safe from the coronavirus.

GOING FURTHER

To win demands, of course, will require more than conversations; you and your co-workers will have to take group action. Your legal right to organize includes the right to:

- file grievances

- hold rank-and-file meetings

- visit the boss in a group on non-work time

- distribute leaflets at work on non-work time, in non-work areas—such as the parking lot, time clock, cafeteria, or break room—and use company-provided, general-use bulletin boards

- solicit signatures on a petition on non-work time, even in working areas

- wear buttons

- pressure the boss in other ways

One of the most effective tactics that union and nonunion workers have used to win urgent demands over the last couple of weeks is the impromptu strike. It’s also one of the riskiest.

In a nonunion workplace, you have the legal right to strike at will. But again, legal remedies are slow—now more than ever. What’s more important is your strength in numbers, the power of public pressure, and your leverage to bring work to a halt.

Just this week, Instacart, Amazon, Whole Foods, and meatpacking plant workers are among the nonunion workers who have walked out on strikes over pandemic conditions. For more on organizing without a union right now, tune into a webinar tonight (March 31, 7 p.m. Eastern time, bilingual in English and Spanish): “Organizing without a Union During the Coronavirus.” Details here.

In a union workplace, your contract probably bars you from striking until the contract is up. But despite this lack of protection, bus drivers, sanitation workers, library workers, factory workers, pharmacy technicians, and shipyard workers are among the union members who have pulled quickie strikes to make pandemic demands. None of them got fired, and some of them won immediate gains. The same principles hold for union and nonunion workers alike—root your power in your numbers, unity, and publicity.