The Alligator and the Auto Worker

If the UAW hoped that in exchange for backing productivity increases and partnership it would be welcomed with open arms, it was sadly mistaken. Photo: Jim West

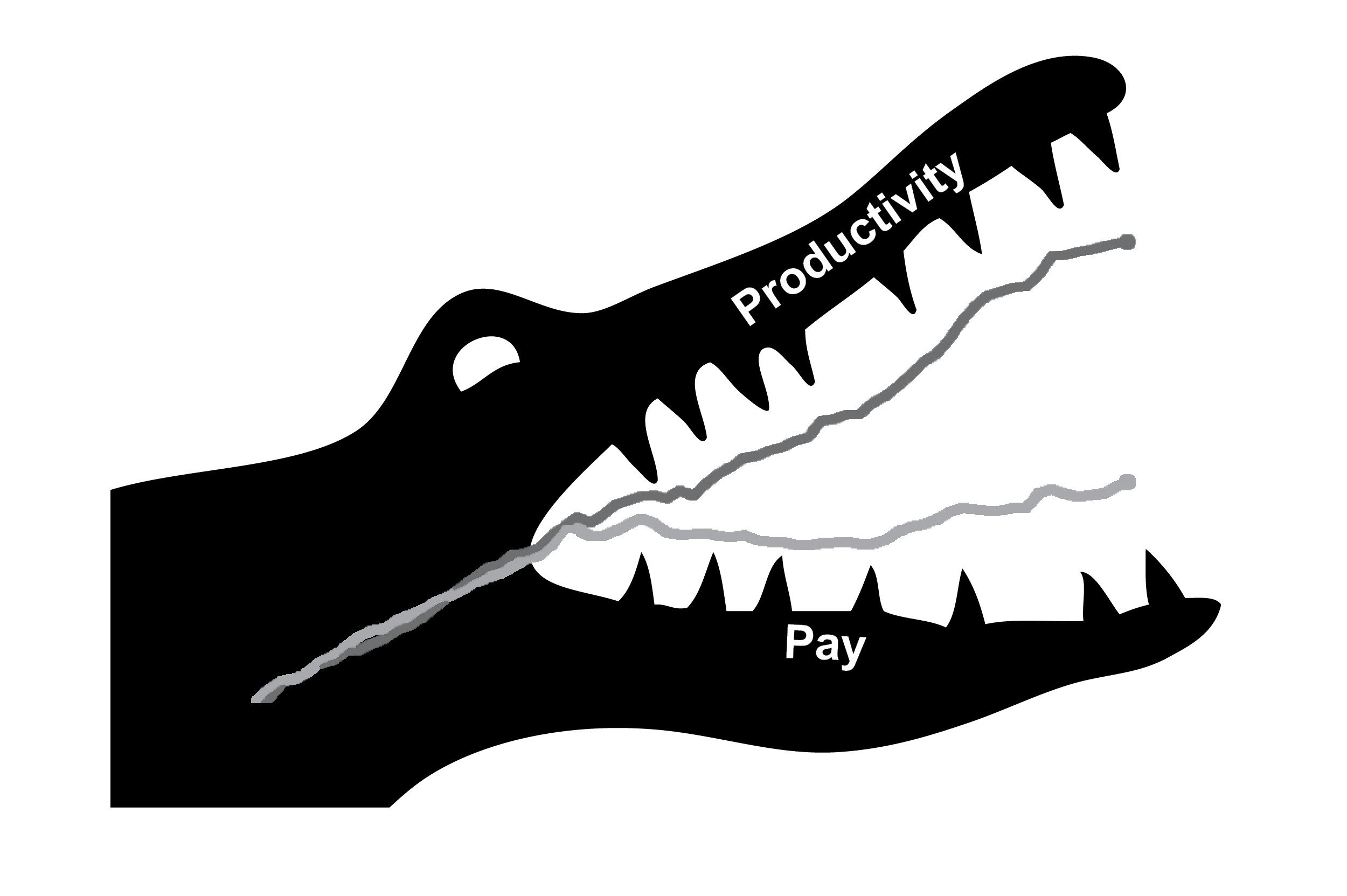

Income inequality is higher today than any time since the Great Depression. One reason why is the widening gap between pay and productivity—a graph that resembles an alligator’s mouth.

Rising productivity is due to more than just robots. Work has intensified through lean production, where fewer workers are pushed to perform more work in shorter times. Workers are electronically monitored so that companies can squeeze maximum profit from every second.

Since 1973, while productivity has climbed, wages have remained stagnant. Hard work does not pay—at least, it doesn’t pay the people who do the work. We are working harder and producing more than ever before, yet the value is going to employers.

Unions should be confronting this exploitation. Instead, the Auto Workers (UAW) signed on to collaborate with it, in a move that reflects the union’s weakness and contributes to its downward spiral.

UNION MADE NICE

The UAW, whose contracts once set the national standard for blue collar workers, lost two-thirds of its members in four decades, dropping from 1.5 million in 1979 to about 400,000 today.

In that time, the union oversaw the erosion of industry standards. It accepted concessions as the Big Three automakers came under competitive pressure from an influx of nonunion, foreign-owned auto manufacturers.

Bob King, then the UAW’s president, told members at a conference in 2011 that “if we don’t organize these transnationals, I don’t think there’s a long-term future for the UAW.”

Hoping to protect what remained, the union planned to spend millions of dollars on a multi-year campaign to organize the South. It set its sights on Volkswagen in Tennessee, Mercedes-Benz in Alabama, Nissan in Mississippi, and BMW in South Carolina.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

But right out of the garage the union was preaching partnership with the employer. According to its “Principles for Fair Union Elections,” a document that King crafted in hopes of wooing management at the transplants, the union “committed to innovation, flexibility, lean manufacturing, world best quality and continuous cost improvement.”

In other words, rather than slamming the alligator’s mouth shut, the union promised to work with the employer to prop it open even wider.

EMPLOYERS DIDN’T BITE

Putting millions of dollars into organizing the South is the kind of bold vision that labor needs. But if the UAW hoped that in exchange for backing productivity increases and partnership it would be welcomed with open arms, it was sadly mistaken.

Instead, the union met predictable hostility from employers. Nissan fought tooth and nail. And at Volkswagen, when just a small unit of skilled-trades workers won a union vote, the company refused to bargain.

Meanwhile the UAW’s strategy of kissing up to exploitative employers backfired, leaving pro-union workers like Wayne Cliett disillusioned.

Workers do not join unions to partner with management. They join because there are serious problems on the job that they want to fix—problems like speedup and surveillance—and because they believe a union can help. In the best campaigns, workers build that confidence through collective action on the job, but that isn’t part of the UAW playbook.

It’s a vicious cycle. Due to pressures from nonunion competitors, the union accepts concessions at the Big Three. Then nonunion employers point to those concessions as evidence the union has no power. Why would you risk your job to join a union that can’t or won’t stand up to the boss?

So the UAW has to organize the South in order to hold its ground at the Big Three—but it also has to hold its ground at the Big Three in order to organize the South. Unfortunately, it has not been able to do either.