A Strike against Squeezing Profits from Kidney Patients

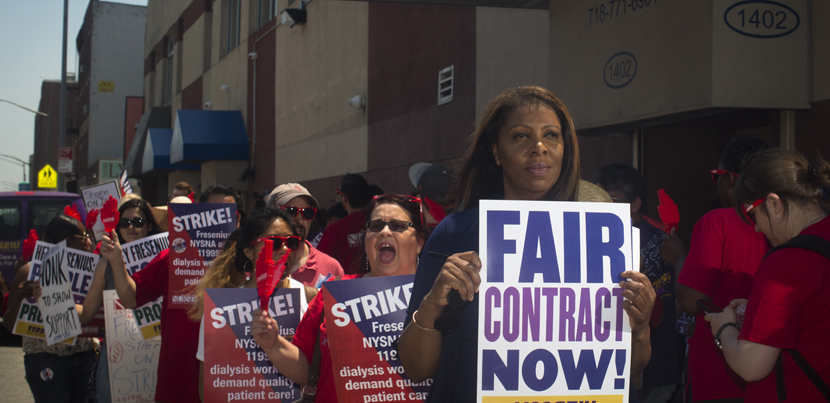

Kidney patients showed up to walk the picket lines with health care workers on a one-day strike. Photo: Dave Sanders

On June 12 Teresa Schloth, a Brooklyn dialysis nurse for 32 years, walked out on her first-ever strike. She and her co-workers are battling a billion-dollar corporation that’s trying to wring greater profits out of kidney patients by skimping on staffing and shifting jobs out of the unions.

People with chronic kidney failure—the technical name is end-stage renal disease—qualify for Medicare regardless of age. Three times a week they go in for dialysis, where they spend hours hooked up to a machine that cleans their blood.

Over the years patients develop a close bond with their caregivers. So despite 93-degree heat, kidney patients showed up to walk the picket lines with health care workers from the New York State Nurses (NYSNA) and 1199SEIU during the one-day strike at seven area dialysis clinics run by the German for-profit Fresenius.

Passing cars tooted their horns in support. And for the workers’ part, turnout at Schloth’s facility was 100 percent. The experience was “invigorating,” she said—and she hopes it sends a message to Fresenius “that we mean business,” especially about short-staffing.

PRIVATIZATION CREEP

Back when Schloth’s facility in Central Brooklyn was publicly run, the ratio was nine patients per hemodialysis nurse. Now it’s 12 patients apiece.

That means each nurse monitors 12 people who are simultaneously hooked up to dialysis machines; she cycles among them, checking their vital signs. “It’s almost like a factory, sad to say,” Schloth said. Many patients have other chronic health issues, and their condition can change quickly. While a nurse responds to one patient’s emergency, another nurse must pile the other 11 patients on top of her own caseload.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

NYSNA wants a Staffing and Professional Practice Committee, made up of half workers and half management, to hash out patient care concerns. This is a system it has won in every union hospital in the city—but Fresenius won’t even consider it.

New York state law bans for-profit hospitals. But although these dialysis clinics used to be run as part of nonprofit or public hospitals, they were spun off into private physician practices in the 1990s. Then Fresenius bought out the doctors for handsome sums. It was part of a national wave, as Fresenius and another company, DaVita, gobbled up the dialysis market. Between them they now control 3 out of 4 chronic dialysis facilities in the U.S. Almost all are nonunion.

IN BAD FAITH

The profits in this business come largely from public dollars, since Medicare and Medicaid pay most of the bills. But the most lucrative patients are those who have commercial insurance too—which doesn’t describe the low-income populations served by the striking clinics in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

Fresenius has closed some union clinics and made no secret of its plan to close more, transferring patients and workers to its new mega-clinic on DeGraw St. in Brooklyn’s ritzy Park Slope neighborhood. The nurses say they bargained for two years over the process; people bid for jobs and were offered shifts. But in October Fresenius abruptly went back on its word and opened the clinic nonunion.

By now NYSNA has been at the table for three years seeking a new contract, and 1199SEIU for two years. Until recently the employer was seeking to pull out of the union pension and benefits funds. The nurses say Fresenius recently indicated it would drop those concessions—but only if the union dropped its claims to the DeGraw jobs, a topic that wasn’t even on the table before. The unions have filed a raft of unfair labor practice charges alleging bad-faith, regressive bargaining.

Just before the strike, a union delegation traveled to Germany to seek support from dialysis workers there, members of the union ver.di—who have a formal voice on Fresenius’s board of directors through their works council. Schloth represented the nurses. She says German workers were instantly supportive, because they’re fighting short-staffing themselves. “Their issues are the same as ours,” she said.