Peter Winkels, the former business agent for Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local P-9—which gained worldwide fame for its 1980s strike against the highly profitable Hormel Co.—died on April 23. Winkels, who had suffered from diabetes and other illnesses, was 69.

“Petey” was a second-generation Hormel worker, employed during the early 1980s in the boning room at the company’s state-of-the-art Austin, Minnesota, pork-packing plant. He rose to a position of leadership along with other militant young rank and filers, including local President Jim Guyette and Vice President Lynn Huston, in a wave of membership rejection of company demands for wage and benefit cuts.

Key to the strike were the energy and intelligence of younger workers now employed in an unforgiving, dangerous, high-speed workplace—and the historical memory of older workers and retirees who recalled a time when workers, not supervisors, had dictated the pace of work. Local P-9 had a proud history as a 1930s outgrowth of the radical Industrial Workers of the World.

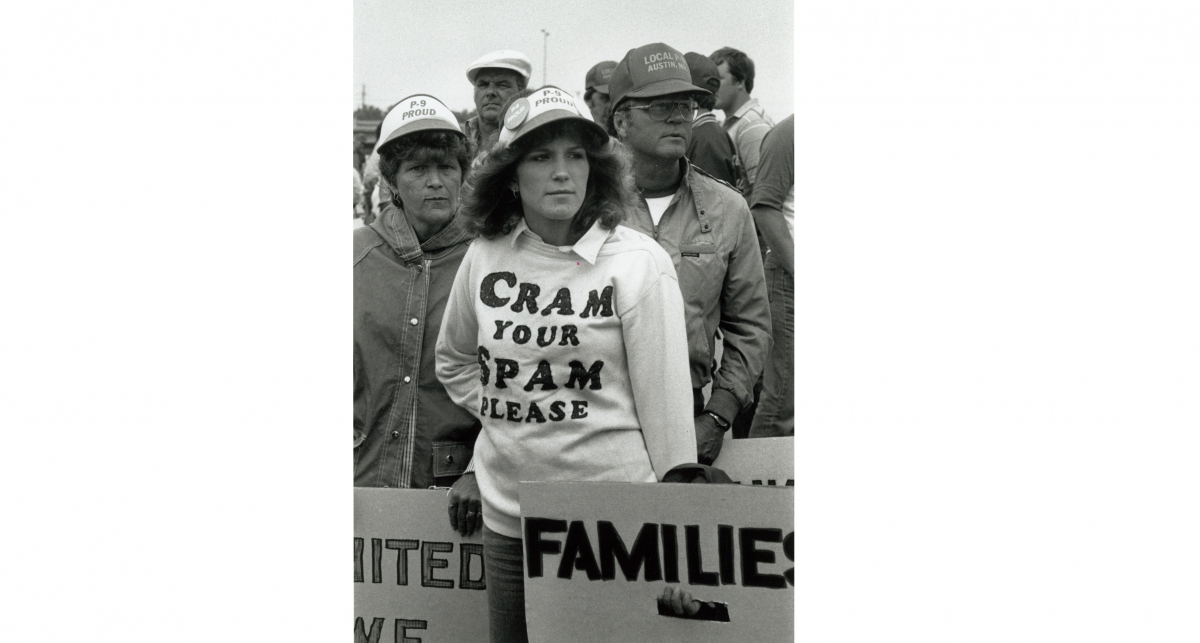

The 1985-86 Hormel strike drew global attention for its creativity, member participation, and militancy during the Reagan era of labor losses. Local P-9 was bucking its national union, which encouraged givebacks and collaboration with the company in what it dubbed a “controlled retreat.” UFCW misrepresented and bad-mouthed the local, and in 1986 placed it in receivership—removing local control—in order to end the strike and turn the union over to those who had crossed the picket line. The scabs became the new union. But many strike supporters will never again purchase a Hormel product.

All this is a matter of public record. But Winkels will be remembered not only for his staunch support of the union campaign, but also for his outrageous and often ribald sense of humor.

In a 1985 meeting with workers from Hormel’s plant in Ottumwa, Iowa, Winkels delivered one of his legendary stories to illuminate the concessions trend. On the drive down from Austin, he said, he’d stopped at a farmer’s house to use the facilities. While he was in the outhouse, a UFCW representative also came in. Somehow, the UFCW man accidentally dropped a dollar down the hole into the excrement below. Then, as an astonished Winkels looked on, the rep proceeded to throw in his wallet, a gold watch, and his gold rings. (The national reps, and particularly its officers such as President William Wynn, were notorious for their ostentatious jewelry.) “What on earth are you doing?” Winkels asked. The rep replied: “You don’t think I’m going down there just for a lousy dollar, do you?”

The Ottumwa meeting reflected the local’s outreach to other unions and communities far beyond Austin. Early in the strike, a number of committees formed, including a food bank and an emergency hotline; so did a United Support Group, which gave spouses and other family members a way to participate. The local leafleted thousands of homes in Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. In Minneapolis and other cities, members demonstrated en masse in front of locations of Hormel’s ally, First Bank. They distributed special editions of their union newspaper describing the strike issues and workers’ horrific injuries from knives, meat grinders, sausage stuffers, and repeated motions. And particularly once Ray Rogers’ consultancy Corporate Campaign came on board, the local initiated a massive fundraising effort to supplement the union’s paltry $40-a-week strike pay. The results included the Adopt-a-Family Fund, which drew donations from around the globe to the tune of $1 million—some of which the national union later diverted to itself.

Strikers traveled singly and in large multi-auto “caravans.” They spoke before union gatherings from coast to coast; in response, P-9 support committees sprang up, from the Bay Area to Boston. Backers from as far away as Ireland and Angola flocked to Austin to witness standing-room-only union meetings and participate in union marches. The strike drew coverage from national TV outlets, The New York Times, and virtually every sort of publication—including, of course, Labor Notes.

But this article is supposed to be about Pete! Winkels was of Native American ancestry and was adopted by Casper and Blanche Winkels in 1949. As a youth, he enjoyed fishing, swimming, Boy Scout activities, and, later, driving in drag races. Once the strike was broken, some workers were recalled, but many, including Pete, were not. He found employment at the Sheriff’s Boys Ranch and Espeland Van Service. And he remained a rebel, blisteringly scornful of those whose anger over deindustrialization and job outsourcing led them to support now-President Donald Trump.

Farewell, Petey—and wherever you are “Cram Your Spam, Please!”

Hardy Green is the author of On Strike at Hormel (Temple University Press, 1990)

![A group of serious-faced people stands indoors. Some are wearing matching red EW4D T-shirts, including Iris Scott, a white woman speaking from notes while others listen and someone in front of them holds up a phone camera to livestream the event. Some in the group wear other union shirts. Handwritten signs on the table in front of the group say "We need true reprsentation," "Vote for worker power," and "UFCW 3000, UAW, TDU" [with hand-drawn logos].](https://labornotes.org./sites/default/files/styles/related_crop/public/main/articles/Iris%20Scott%20speaks%20at%20EWD%20press%20conf%20april%20photo%20TDU%20cropped.jpg?itok=_KmoC2lJ)