“You know you’re getting the short end of the stick as a worker, but you don’t really know why,” says Joe Tarulli, a Staten Island Verizon tech who’s put in 17 years with the company. “They make it seem like these rich people are just lucky they got the right chances, and these poor old working folks, nothing ever goes right for them. No! These corporations are doing it on purpose.”

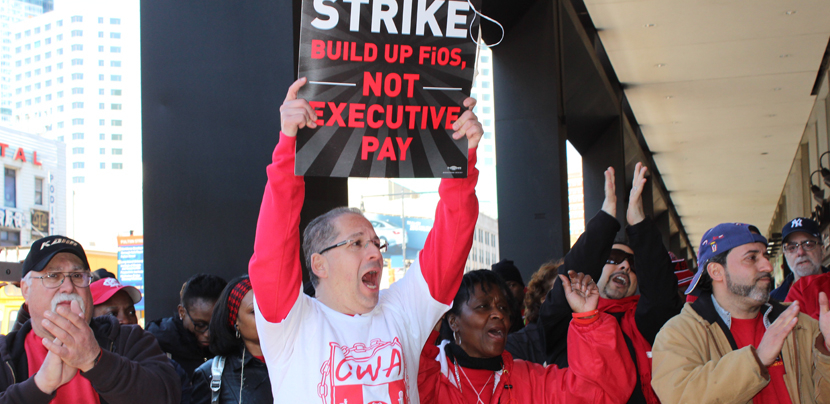

Last spring, Tarulli and 39,000 Verizon workers were forced out on a 49-day strike to fend off outsourcing and other concessions demanded by the company, even as it raked in billions in profits. Democratic primary candidate Bernie Sanders walked the picket line with them to draw media attention to their battle against corporate greed.

But in the general election, Tarulli says many of his co-workers went on to vote for Donald Trump, who spoke to the anger that had motivated them to strike in the first place. “Trump’s a great communicator,” says Tarulli. “For a long time people felt ignored, even by their own unions, because these companies take advantage of them so badly.”

Trump’s win highlighted a rank and file that feels alienated from politics as usual. While most major unions backed Hillary Clinton, 43 percent of voters in union households cast their ballots for Trump. The swing in votes was less a bump for Trump (who outperformed Mitt Romney by 3 points in union households) than a shortfall for Clinton (7 points below Obama in 2012)—and that’s not counting those who simply stayed home.

“I did believe in him trying to get more jobs back to the United States,” says Trump voter Jack Findley of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Findley worked for four years on a Volkswagen assembly line, backing the unsuccessful union drive at the plant in 2014 before an injury put him out of commission. He has two kids, ages 4 and 7, and worries as he watches power companies and retailers in his area shut down. “When my kids get old enough, I don’t know where they’re going to be working,” he says.

It’s difficult to fathom that workers who risked their livelihoods to take on a corporate behemoth like Verizon, or back a long-shot union campaign at Volkswagen, went on to vote for a poster child of corporate greed. But after decades of bipartisan fervor for privatization, budget cuts and so-called free trade deals, many workers are disillusioned with both parties.

“Let’s be honest—one party is directly against us, and one party helps us every now and then,” says Scott Hoffman, president of the Postal Workers (APWU) Boston Metro Area Local. “I think so many union members, and union leadership for that matter, strayed this time because they felt that when they did put people in, the effort didn’t come back.”

From the outset of election season, labor should have been better in touch with this sentiment than anyone; its members were canaries in the coal mines that Trump has sworn to reopen. In January 2016, for example, the group Working America warned that the candidate’s fiery denunciations of free trade agreements were winning over white union members in the Rust Belt.

Yet just a handful of national unions—including APWU, the Communications Workers, and National Nurses United—were willing to throw in their lot with Sanders’ campaign, which channeled the anger and despair of working people toward the real culprit, corporate America.

The lesson of 2016 is clear for labor: Working-class people are angry at the degree of American inequality, desperate for an explanation of how we got here, and ready to take drastic action, if presented to them. Whether they opt for Trump and Steve Bannon’s racism or take to the streets against the 1% depends largely on how unions decide to fight back.