‘Striking on the Job’: Joe Hill’s Living Message

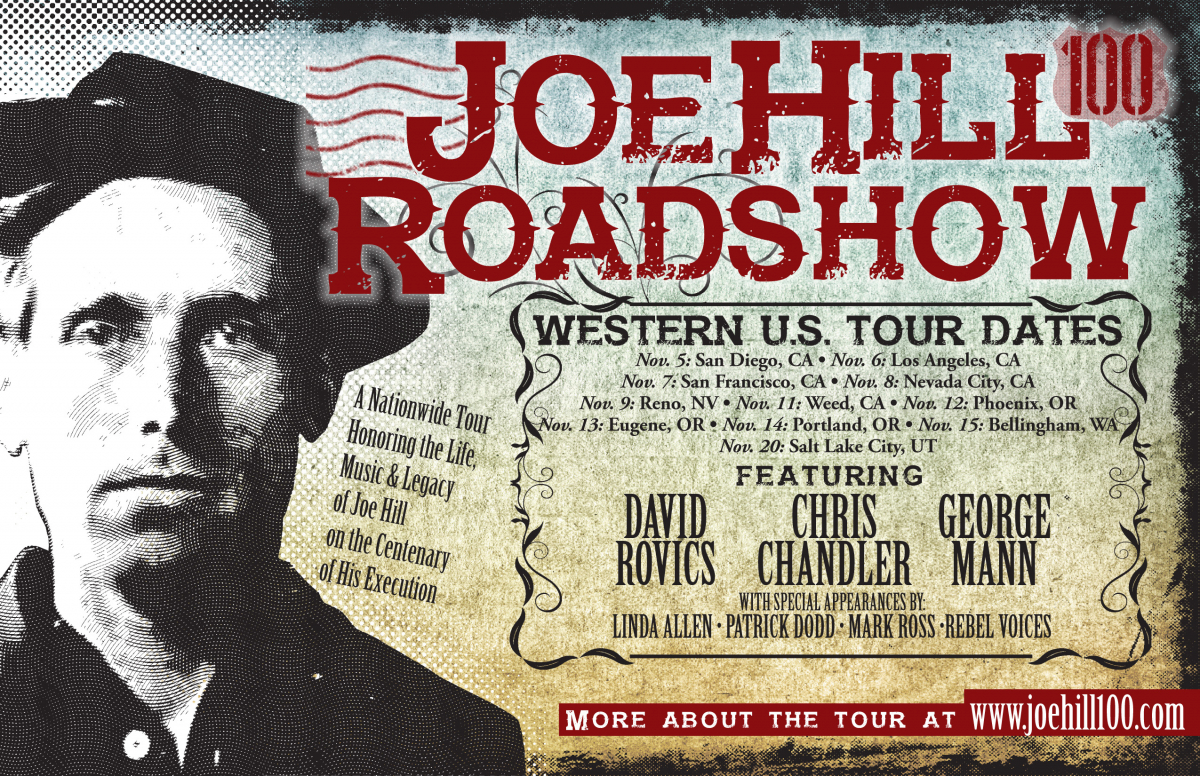

The Joe Hill 100 Roadshow’s Western Leg concludes tomorrow with a grand finale concert in Salt Lake City, where the iconic labor troubadour and troublemaker was killed a century ago.

Featuring Otis Gibbs, Duncan Phillips, Kate Macleod, Walter Parks and many special guests. $15.

When: November 20, 2015. Doors at 7 p.m., concert 8 p.m.

Where: The Stateroom, 638 South State Street, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the execution of Joe Hill, the iconic labor troubadour and troublemaker.

The anniversary is being marked with concerts and other events across the U.S. and with the release of an expanded edition of The Letters of Joe Hill, including all his surviving articles, letters, poems, and songs.

Like millions of immigrants today, Joe Hill lived much of his life in the shadows and on the road. He worked the odd jobs available to immigrants.

He was pressganged into rescue work after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, had to talk his way out of deportation when he returned to the U.S. after joining other Wobblies (members of the Industrial Workers of the World) who fought alongside the Magonistas in the Mexican Revolution, and was routinely harassed by police—as an agitator, but also because he was poor.

At age 36, Hill was convicted and executed in Salt Lake City on what are widely seen as trumped-up murder charges. Despite a near-complete lack of evidence, Utah’s governor—who had campaigned on the promise to crack down on unions in the mines, where Hill was working—refused to commute the sentence or grant Hill’s demand for a new trial.

Today, thanks to biographies by William Adler and Gibbs Smith, we know a great deal about Hill’s life and the sordid conspiracy that took it from him.

But even a century ago, his fellow workers recognized the crime. Hundreds of thousands joined protests, wrote letters, and passed resolutions demanding Hill’s release. Thirty thousand thronged his funeral in Chicago. His ashes were scattered the world over.

A Sampling of Joe Hill’s Songs

“The Rebel Girl,” performed by Alyeah Hansen

“The Preacher and the Slave,” performed by Utah Phillips and Ani DiFranco

“We Will Sing One Song,” performed by Six Feet in the Pine

“It’s a Long Way to the Soup Line,” performed by John McCutcheon

“Casey Jones the Union Scab,” performed by Mark Ross

…And One About Him

“I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night,” lyrics by Alfred Hayes, music by Earl Robinson, performed by Paul Robeson

LETTERS AND SONGS

During his five years as a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, Hill wrote dozens of songs and several articles and poems for the IWW press.

He served as strike committee secretary during a dockworkers strike in San Pedro, California. He traveled to British Columbia to lend a hand to railroad construction workers in the Fraser River strike, where his songs bolstered morale along the legendary 1,000-mile picket line.

The new edition of his letters restores the full text of two letters excerpted in the first edition, adding 16 letters and other writings discovered since then and all his surviving songs.

It’s far from complete—no letters survive from Hill’s first eight months in jail, and very few of his pre-arrest letters have been saved.

Four surviving postcards sent to a fellow Swedish immigrant turned up only decades after Hill’s execution. The cards were sent care of the Sailors Union hall, and evidently carried in a sea bag for years.

Much of Hill’s correspondence was surely lost by recipients who did not realize its historical significance—or was destroyed, like the transcripts of the judicial proceedings against him, by officials who did.

27 WAYS OF STRIKING

When the San Pedro dockworkers called off their strike in 1912, Hill wrote:

The I.W.W. has 27 different ways of striking and after we have tried the remaining 26 varieties the Stevedoring Companies may be willing to grant our demands.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

We pulled out about 600 men … and the tie-up would have been complete had it not been for 10 or 12 of my-country-‘tis-of-thee stiffs with sick wives, and lots to pay installments on, and other similar excuses. They are strongly in favor of an increase in wages, but when it comes to making a fight for it – Oh No! Nothing doing!

Striking on the job, Hill believed, was essential. In an article he wrote from prison for the International Socialist Review, he returned to this theme:

If every worker would devote ten or fifteen minutes every day to the interests of himself and his class, after devoting eight hours or more to the interests of his employer, it would not be long before the unemployed army would be a thing of the past and the profit of the bosses would melt away so fast that they would not be able to afford professional man-killers to murder the workers and their families in a case of strike.

The best way to strike, however, is to ‘strike on the job.’ First present your demands to the boss. If he should refuse to grant them, don’t walk out and give the scabs a chance to take your places. No, just go back to work as though nothing had happened and try the new method of warfare.

When things begin to happen be careful not to ‘fix the blame’ on any certain individual… The boss will soon find that the cheapest way out of it is to grant your demands.…

Striking on the job is a science and should be taught as such.… It develops mental keenness and inventive genius in the working class and is the only known antidote for the infamous ‘Taylor System.’

The aim of the ‘Taylor System’ seems to be to work one-half of the workers to death and starve the other half to death. The strike on the job will give every worker a chance to make an honest living.… It will stop the butchering of the workers in time of peace as well as in time of war.

WHAT WE WANT

True freedom, Hill believed, could only come from an organized working class recognizing its common humanity and acting together in its own behalf.

In “Scissor Bill” and other songs he ridiculed workers who thought they were better than others because of their craft, ethnicity, or race. He condemned police brutality in his very first Industrial Worker article, “Another Victim of the Uniformed Thugs,” and returned to the subject in several songs.

In many of his letters and songs, Hill urged women to organize. His 1913 song “What We Want” couples the organization of “the sailor and the tailor and the lumberjacks” with “all the cooks and laundry girls… the trucker and the mucker and the hired man, and all the factory girls and clerks. Yes, we want every one that works in one union grand.”

He wrote about the billions spent on guns and ammunition while millions lived in misery (indeed his very last song, written on the eve of his execution, condemned the human cost of the war raging in Europe), the homeless chased from town to town, sweatshops and temp jobs, and the plight of workers condemned to the scrap heap once the bosses had extracted every last bit of profit.

But he also wrote of hope, of the possibilities for a better world. Sitting in prison awaiting execution, Hill was asked to write a song about unemployed workers forced to turn to soup kitchens. In his song, “It’s a Long Way Down to the Soupline,” he wasn’t content to bemoan their plight:

Bill and sixteen million men responded to the call,

To force the hours of labor down and thus make jobs for all.

They picketed the industries and won the four-hour day…

This cheerful ditty about unemployment ends like this:

The workers own the factories now, where jobs were once destroyed

By big machines that filled the world with hungry unemployed.

They all own homes, they’re living well, they’re happy free and strong,

But millionaires wear overalls and sing this little song.

JOE HILL NEVER DIED

Joe Hill never died. So says the song written two decades after his execution, and sung since then the whole world over.

His legacy lives on not only in his songs, but also in his vision of a labor movement that organizes across borders, empowers workers to act on their own behalf, and stands for a better world:

If the workers take a notion, they can stop all speeding trains;

Every ship upon the ocean they can tie with mighty chains.

Every wheel in the creation, every mine and every mill,

Fleets and armies of the nation, will at their command stand still.…Workers of the world, awaken! Rise in all your splendid might;

Take the wealth that you are making, it belongs to you by right;

No one for bread will be crying, we’ll have freedom, love, and health;

When the grand red flag is flying in the Workers’ Commonwealth.—“Workers of the World Awaken,” written in the Salt Lake City prison in September 1914

Jon Bekken is co-author of The Industrial Workers of the World: Its First One Hundred Years, former editor of the IWW’s Industrial Worker newspaper, and associate professor of communications at Albright College.