Retirees, Watch Out: Detroit May Become Blueprint for Other Cities

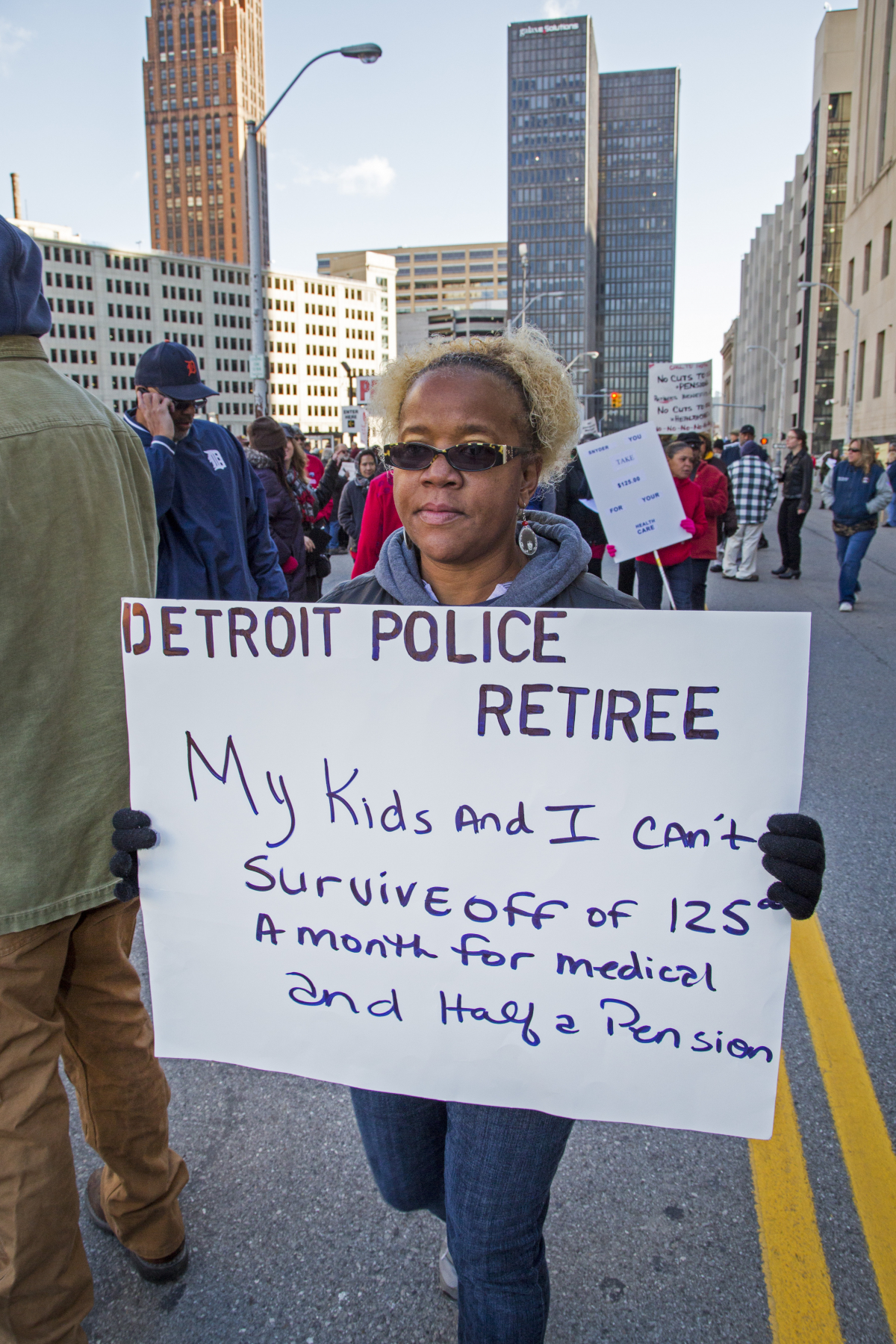

Detroit's court-approved "plan of adjustment” to exit bankruptcy includes a staggering cut to retiree benefits. Photo: Jim West/jimwestphoto.com.

Here’s what’s really being missed in most snapshot explanations of Detroit’s bankruptcy: the unprecedented hit being taken by retirees who believed that, after working throughout their lives, they would be secure in their old age.

And Detroit sets a dangerous precedent. Your city’s retirees may be next in the crosshairs.

U.S. Bankruptcy Court Judge Steven Rhodes’s ruling that public employee pensions could be reduced in Chapter 9 bankruptcy was a “landmark decision,” says John Pottow, a University of Michigan Law School professor who specializes in bankruptcy.

Rhodes in November approved the “plan of adjustment” for Detroit to exit bankruptcy. A formal end to the bankruptcy is expected to occur later this month, after the city produces a two-year budget that adheres to the provisions laid out in the plan of adjustment that includes a staggering cut to retiree benefits.

That plan, says Pottow, “could well be a blueprint for other pension-choked cities.”

PENSIONERS TARGETED

From the start, it was clear that Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr saw it as his mission to go after—rather than protect—pensioners.

In fact, it was lawyers from Orr’s former firm, Jones Day, who laid out the legal framework for using Chapter 9 bankruptcy as a way for cities and other units of government to shed pension obligations.

Now, with Jones Day playing the lead role in representing the city during bankruptcy, Detroit turned out to be the place where the theory of pension vulnerability was put to the test.

This is the result: Despite having the protection of public pensions etched into the Michigan Constitution, it is retirees who, by far, are the ones bearing the financial burden of Detroit’s bankruptcy.

From the start, the figure for debt and liabilities owed by the city, $18 billion, has been a fiction, pumped up by Orr and crew to help ensure Detroit was declared eligible for bankruptcy. About $7 billion of the $18 billion will be trimmed in bankruptcy, according to the most recent news accounts.

Of that $7 billion, it appears as if nearly 80 percent is being taken from retirees.

BIGGEST HIT: HEALTH CARE

Because the numbers are slippery, it’s not possible to put an exact figure on how much is going to come out of the pockets of retirees. It is possible, however, to get some idea.

The biggest hit comes in the form of health care cuts, already instituted as a result of actions taken by Orr.

Instead of being enrolled in health insurance plans where they pay 20 percent of the cost and the city picks up the rest, the vast majority of retirees are now receiving $125 monthly stipends. (Some, such as police and firefighters injured on the job, receive as much as $400.)

That reduction is the single largest “debt” the city will be shedding—about $4 billion.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

As a result, retirees have seen their insurance costs skyrocket. Cecily McClellan, who spent 18 of her 23 years with the city working at the health department, says her health care costs have jumped to about $500 a month.

“Many people who thought they had a decent nest egg are going to find themselves living in poverty,” she says.

PENSIONS AND SAVINGS CUT TOO

On top of the health care cuts, general retirees, whose pensions average around $19,000 a year, will also suffer a 4.5 percent reduction in their pensions. Police and firefighters, because they aren’t eligible for Social Security, will see no cuts to their current pensions. Both groups, however, will be hit hard by reductions to annual cost of living (COLA) increases.

Though this fact tends to receive little coverage in the media, the consequence is significant.

According to a report produced by Kim Nicholl, an actuary who advised the Retirees’ Committee appointed by Judge Rhodes, the COLA cuts will reduce future payments to general retirees by about $616 million, and to police and firefighters by some $688 million, for a total of more than $1.3 billion.

Finally, there’s the recoupment of alleged interest overpayments into annuity savings accounts that many city workers contributed to as part of their retirement planning. That so-called “claw back” will take more than $190 million from retirees who participated in the program from 2003 to 2013. The money will be deducted from future pension payments.

“The way I see it, I’m getting hit four different ways,” says Belinda Myers-Florence, who worked for the city more than 35 years. “They’ve taken my medical care; there’s the annuity savings recoupment; they’re taking away the cost of living increases; and there’s the 4.5 percent reduction to my pension.

“When I take the time to talk to people and tell them what’s really happening, they say they had no idea.”

HELP FROM RETIREES ELSEWHERE?

One person who has been trying to raise awareness of the bankruptcy’s real impact is William M. Davis, president of a group known as the Detroit Active and Retired Employee Association. Davis has been peppering the bankruptcy court with objections to the plan.

Davis, who spent 34 years working for the city’s Water and Sewerage Department, knows the deck is stacked against him at this point. Nonetheless, he and members of his group continue to meet weekly and strategize about what their next steps might be.

A lawsuit challenging the bankruptcy court’s decisions is a possibility, he says. But doing so will be difficult because potential allies—ones with pockets deep enough to pay the massive legal bills that would accompany a legal challenge, such as unions representing city employees—agreed not to pursue an appeal as part of settlement agreements.

As bad as this deal is, they figured, it might have been worse. Orr threatened that pension cuts could be as high as 27 percent if a settlement—one that included more than $800 million from the state, private foundations, and the Detroit Institute of Arts to cushion the blow to retirees—wasn’t agreed to.

One possibility, says Davis, is that retiree organizations from elsewhere in the country might come to their aid, in an act of enlightened self-interest, to help provide the funds for an appeal suit.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Metro Times newspaper. Curt Guyette is an investigative reporter for the ACLU of Michigan. His work, which focuses on Michigan’s emergency management law and open government, is funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation. Contact him at cguyette[at]aclumich[dot]org.