Review: Cesar Chavez Remembered, Warts and All

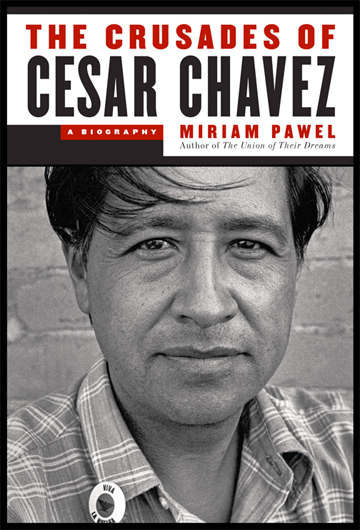

The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography, by Miriam Pawel, 2014. Our reviewer chooses the book over two recent Chavez films, one a biopic, one a documentary.

Movie: “Cesar’s Last Fast,” directed by Richard Perez, 2014.

Movie: “Cesar Chavez,” directed by Diego Luna, 2014.

Book: The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography, by Miriam Pawel, 2014.

“Cesar was not a humble man,” narrator Luis Valdez says at the conclusion of the new documentary “Cesar’s Last Fast,” about the late farm labor leader Cesar Chavez. “Nor was he a simple man.”

Indeed, Chavez was a controversial and complex figure. That’s the problem with Diego Luna’s feature film “Cesar Chavez,” whose release coincided with the charismatic leader’s March 31 birthday.

Chavez was, of course, a genius and a master organizer. His successes in the vineyards and lettuce fields of California came about as a result of enormous personal sacrifice and his ability to reach out to a wide audience: students, priests, nuns, ministers, labor leaders, and average housewives who made up their minds not to buy grapes.

He broke the back of the open shop in the fields and is credited as a founder of the Chicano movement. Just a decade after he began organizing grape pickers in Delano, California, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

But Chavez as portrayed by Michael Peña is a flat, one-dimensional character who does everything unassisted—from leading picket lines to negotiating with growers and signing contracts with them.

The organizers on whose shoulders he stood are ignored or reduced to bit players. And the Filipino farm workers who were the first to go on strike are nearly erased.

There is no mention of Chavez’s closest advisers, such as the Migrant Ministry’s Chris Hartmire or Marshall Ganz, the son of a rabbi, who served as director of organizing for the United Farm Workers (UFW)—and little acknowledgement of the critical role played by women such as the union’s co-founder Dolores Huerta or Jessica Govea, a key organizer.

There are no nuances in Chavez’s character, no references to his legendary fights with his own staff or to his cultic, authoritarian, and often abusive leadership style.

It’s no wonder, since the script was carefully vetted and approved by the Chavez family and their foundation. The result is a biopic that treats its subject with reverence rather than objectivity. We no more get to know Chavez in this film than we would understand who St. Francis was by gazing at his statue in a church, illuminated by flickering candles.

Yet I would not discourage anyone from seeing “Cesar Chavez.” Its pacing is good. The villains are fun to watch. Since I was there, I can testify that the sheriffs’ deputies and the goons beating the workers are real, not exaggerations.

John Malkovich does an excellent job as a conflicted and wily grower, and Rosario Dawson presents a credible—though understated—Dolores Huerta. Huerta in real life has never had a problem filling a room or a screen with her presence; her talents are often glossed over in the popular media.

His Last Fast

Richard Perez’s documentary, “Cesar’s Last Fast,” comes much closer than Luna’s feature film to explaining the struggle of the farm workers, including those who sacrificed their lives to win the grape and lettuce contracts.

In the late 1980s, with fewer contracts and limited successes with the grape boycott, Chavez decided to go on another lengthy fast, this one lasting 36 days. It took its toll on his health—yet did not bring growers to the bargaining table. Chavez had depleted all his resources, and attempts to revive the union had failed.

The film tells the story of Chavez’s life and organizing career from the 1950s until his death in 1993. In-depth interviews with UFW co-founders Huerta and Gilbert Padilla, and with Chavez aides LeRoy Chatfield, Ganz, and Hartmire, present not only the events—the fasts, marches, and sit-ins—but also the motivations and brilliant strategies behind them.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Perez also gives us a glimpse, though fleeting, of Chavez’s dark side, with his insistence that his staff play the Synanon “game.” This consisted of rather ugly encounter sessions where individuals were “gamed” by heaping insults and obscenities on each other.

Charles Dederich, director of Synanon (a cult that had grown out of a drug rehab program), persuaded Chavez that the game was helpful in consolidating his control over his followers. Chavez agreed, but the results were disastrous for the union and a prelude to its eventual breakdown.

Truth Is in the Writing

“Cesar’s Last Fast” opens the Pandora’s Box just a crack—but a recent spate of books on Chavez and the UFW really tells the sad story of the union’s decline from the late 1970s to the present.

Frank Bardacke filled in the details of the union’s decline in Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers (2011). Matt Garcia provided further analysis of these events in From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement (2012).

Miriam Pawel offers the most comprehensive look at Chavez and his movement in her new book, The Crusades of Cesar Chavez. Pawel already broke new ground on Chavez and the UFW in her previous book, The Union of Their Dreams (2009), a study of key figures in the union’s 40-year struggle.

In The Crusades, Pawel offers a smooth, well-written, and well-researched narrative of Chavez’s life. She traces his roots from a Depression-era farm near Yuma, Arizona, through his early years as an organizer, through his endless campaigns with the UFW.

If there’s a theme to the book, it’s the constant tension between building a broader movement and sustaining a union—with all the prosaic and demanding tasks that must be done to fulfill the stipulations of contracts.

Pawel documents the fact Chavez and his organizers could never really accomplish the union part. And at the end of the day, Chavez never wanted to do it. The fasts, marches, and boycotts worked magically—but once the contracts were signed, the union couldn’t competently administer the hiring halls. This generated a backlash from both workers and growers.

“Cesar turned away from the union around 1977,” Padilla told me. “He no longer wanted to deal with workers. He just wanted to build a cult. After the 1980s, nothing was done. Nothing. Zip.”

An Empty Bag

In the summer of 1977 Chavez disregarded the cautions of his closest advisers and visited the Philippines as a guest of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos—drawing the ire of Filipino farm workers, progressive supporters, and church people. When the Rev. Hartmire, Chavez’s closest adviser, defended the visit, Pawel quotes Monsignor George Higgins of the U. S. Bishops Committee on Farm Labor telling him, “You’ve become so enmeshed in the union that you don’t own your soul anymore.”

Another blunder was the free rein Cesar gave his cousin Manuel Chavez to conduct sabotage operations against growers and beatings of undocumented strikebreakers. Pawel quotes Chavez from a tape recording he made at a New York boycott office: “Manuel does my fucking dirty work.”

By 1990, all of Chavez’s closest people had resigned or been purged from the union, including Huerta. Father Ken Irgang, the UFW’s Catholic chaplain, also left the union’s headquarters. Pawel quotes from a letter he wrote to Hartmire: “I can’t shake my loyalty to the UFW, but Cesar’s behavior is heartbreaking, especially how far he is in reality from the image people have of him.”

Suppose Chavez had stepped aside and put the union in the hands of competent administrators. Would the UFW today be a vibrant, militant union? Maybe. Maybe not.

Pawel ends her book on an upbeat note, suggesting that on balance, Chavez and the UFW left a positive legacy—and one that is still imitated, especially by today’s immigrant rights movement.

California farm workers, though, are worse off now than they were in the 1960s. The UFW has become a family-run business, focused on direct-mail fundraising and its foundation. It has only 5,000 workers under contract. The union has not conducted a large-scale campaign against any major growers since the late 1990s.

What does the UFW plan to do about the low wages that now match those when the union started? What about deteriorating farm worker housing? Where is the strategy?

It appears the farm workers have been left holding an empty bag. They deserve much better. The question is: who will organize them?

Mark R. Day served as a Catholic chaplain and organizer with the United Farm Workers in the late 1960s. He is the author of Forty Acres: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers, Praeger, 1971.