Edging toward International Solidarity

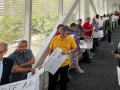

The fruit of years of struggle. In China, visitors said, workers sign a one-page individual contract. Photo: Chun-Yi Lee.

When I was asked to join a labor tour in New York, I didn’t expect American workers to be so curious about Chinese workers.

Even at the Labor Notes conference in Chicago last year, in some panels I faced questions like, “Why have Chinese workers taken away our jobs?”

But on this labor tour in the Big Apple, I saw the possibility of international solidarity blossoming. I realized that it’s a slow process, built on mutual understanding.

Curious

I was part of a group of scholars and students who do research on Chinese labor. To learn about the labor movement in the U.S., and share our own knowledge about China, we spent a week in meetings with rank-and-file activists who’d been on strike (CWA Local 1101 at Verizon); stewards in a Teamsters local at UPS; newly elected reform leaders from the New York State Nurses Association; and fast food workers doing non-majority organizing (Brandworkers).

In almost every meeting, we were asked about how Chinese workers organize strikes without unions and without legal protection. The actual number of these strikes is difficult to gauge, but you can get some idea of their intensity and frequency from the website China Strike.

Although American workers have quite a comprehensive labor law and established unions, they told us, companies hire smart lawyers to undermine workers’ interests and use every possible dirty trick to destroy solidarity.

The American workers we met wanted to make their unions more democratic and less bureaucratic. It is workers themselves who give strength to the union, they said, not union officials.

In China, we told them, workers don’t have unions. They have to rely on themselves to organize strikes. In a certain sense, the scenario that Chinese workers are facing now is similar to what these American workers wish for.

In fact, workers in China have the biggest union in the world, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions. But it does not act on behalf of workers’ rights. All the strikes in China that American workers have heard about are so-called wildcat strikes, not organized by unions.

The truth is that both American and Chinese workers have to stand up to fight for themselves.

Thick as a Book

Members of the Communications Workers (CWA) showed us the contract they have negotiated with several companies in the Northeast. It is as thick as a book.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

This detailed contract—the result of strikes, struggles, and bargaining by more than 55,000 workers—is their pride and joy. They fought for every clause to defend their rights.

The contract keeps growing. Whenever there is a small grey area, workers demand that the boss agree to clarify it.

I am totally amazed by this. The individual labor contract in China is only a piece of paper—sometimes even a piece of blank paper, because workers don’t know they have to the right to sign a contract.

Moreover, the labor contract in China was designed by the government and employer. Workers, ironically, were left out of the process.

More than Wages

Another striking point arose when we asked workers who had been fired for trying to organize a union at Cablevision, “How do you form solidarity among your colleagues?” They told us their vision has to go beyond increased wages. As I understood it, solidarity to them meant building up their co-workers’ trust, support, and care for each other. (The workers did get their jobs back.)

It is not easy to organize collective action. Everybody, whether American or Chinese, fights for his or her own interests. The way to turn human nature to solidarity is to tell co-workers how the injustice will affect not only a small group but the workers as a whole.

After the meeting I casually asked one worker, “How does your family feel about you spending your time on your co-workers?”

He told me, “My son and little daughter are always with me when I go to talk with our co-workers. They live with our movement.”

After hearing that, I wished the participants in these exchanges with American workers were not only scholars and students, but Chinese workers themselves. The beginning of international solidarity is to understand each other.

Chun-Yi Lee is an Economic and Social Research Council research fellow in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She studies the role of Chinese labor in the global economy.