‘Throwing The Heroes Away’: As Arkansas Tyson Plant Closes, Workers Strike over Treatment

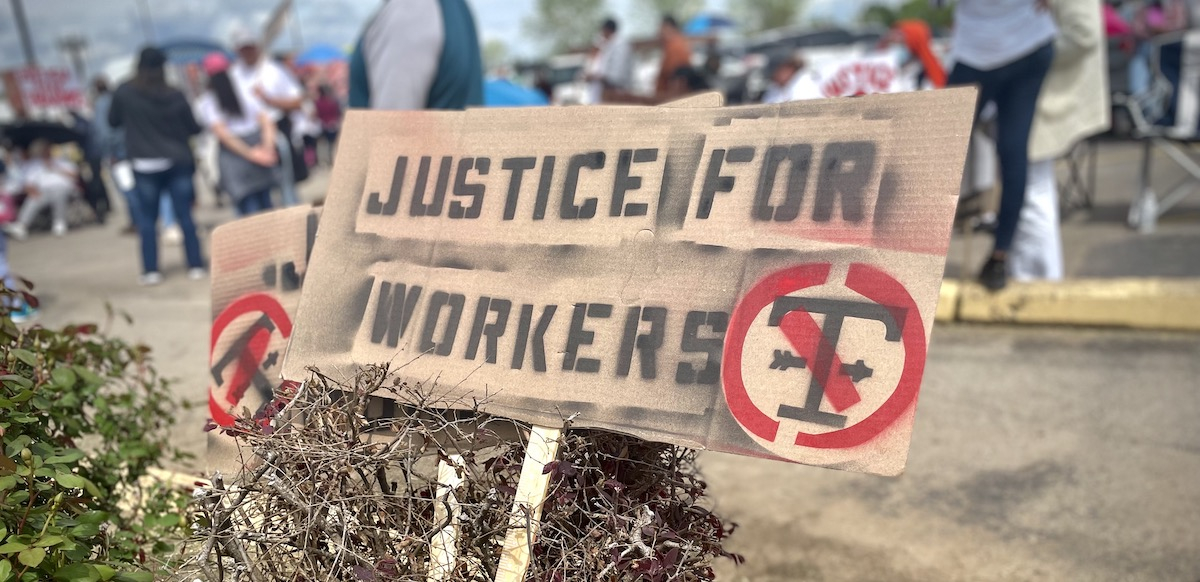

Workers at Tyson Foods’ Van Buren, Arkansas, poultry processing plant struck April 10 after they heard the plant was closing. They asked for equal treatment compared to supervisors and corporate employees, with full severance payouts based on years of service, payouts for unused vacation time, and better handling of workers’ compensation and injury claims. Photo: Rachell Sanchez-Smith.

Published in partnership with Facing South.

Striking workers gathered in front of a Tyson Foods poultry processing plant in Van Buren, Arkansas, earlier this month, holding protest signs reading “Justice for Workers” and chanting in Spanish “si se puede” (“yes we can”) and “juntos venceremos” (“together we’ll win”). A few weeks earlier, they received notice from Tyson—the multinational poultry and meat processing giant headquartered about an hour away in Springdale, Arkansas—that their plant would be shuttered on May 12. The Van Buren plant employs almost 1,000 workers, many of them immigrants from El Salvador, Mexico, and Laos, some of whom have worked there for decades.

The strike began on April 10. The next day, a workers’ delegation delivered a petition to plant management that was signed by more than 300 of the plant’s employees asking for equal treatment compared to supervisors and corporate employees, with full severance payouts based on years of service, payouts for unused vacation time, better handling of workers’ compensation and injury claims, and fairer working conditions. Three days later, workers caravanned by car to the company’s Springdale offices and delivered a letter detailing their grievances to Tyson CEO Donnie King.

About 100 workers participated in the first day of the strike, many joining the picket lines at the same time as they would have started their shifts. Over 60 continued to strike on the following days, taking pay cuts for the days of work missed—and facing intimidation from management. Yesenia Recinos, who has worked for the plant for 19 years, said higher-ups told employees on the strike’s first day that “if we didn’t go to work, we would be replaced by other workers.”

“I figured that they were going to give us points, that they could fire us or retaliate,” she said, referring to the company’s disciplinary points system. “But at the same time, we knew that this is a right that we have, that we can go on strike.”

According to several workers Facing South interviewed, Tyson did not give employees any points for their absence, but it would not allow them to use vacation time to cover the missed days. In an email to Facing South, Tyson spokesperson Derek Burleson said the company has remained in regular communication with the Van Buren workers, including meeting with them to hear their concerns and ensuring they have needed resources available. It’s also coordinating a job fair for the displaced workers.

The company said the closure of the Van Buren plant, which opened in 1975, was for efficiency. Tyson says that workers affected by the closure can relocate to plants in Northwest Arkansas or Texas, but those places are a drive of an hour or more from Van Buren.

“We want justice,” said Aurora Delgado, a deboning worker at the Van Buren plant who’s been with Tyson for 24 years. Delgado is one of 10 Tyson strikers who spoke with Facing South in Spanish about injuries they have sustained from the repetitive motion of poultry assembly lines, and about being undervalued and mistreated on the job.

For example, after months of repeated visits to Tyson’s infirmary, where she says she was treated with “cream” and “Tylenol” for searing pain in her left forearm, Delgado went to a doctor outside the Tyson insurance network. They recommended surgery.

Liliana Ledesma is another line worker who has been at the Van Buren plant for 18 years. She also spent months complaining to management and infirmary staff about the constant pain in her arm, worsened by her position on the processing line. Ledesma was told to keep working through the pain, which has impaired her life significantly.

“I can’t even comb my own hair,” she said. “I can’t lift my arm because of the pain.”

All of the striking workers Facing South interviewed cited concerns about working on a floor that is constantly slippery, flooded with chicken grease, oil, and water. Three employees also cited concerns about trench foot—a debilitating condition caused by prolonged exposure to wet conditions that can lead to serious infections and even amputation.

Tyson did not respond to specific questions about its practices around workplace injuries. Workers across the country have cited Tyson’s in-house medical teams as obstacles to proper care, and as a way to hinder reports and investigations by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

The strikers are frustrated because the company that lauded their essential work during the COVID-19 pandemic now appears to be turning its back on them. As Facing South reported in 2020 and 2021, Tyson plants in Arkansas were ravaged by COVID due to factors including poor safety standards, close quarters within processing plants, and companies’ refusal to shut down production to curb the virus’s spread. At least three workers at the Van Buren facility died of COVID during the pandemic, according to OSHA reports. The family of one worker who succumbed to COVID is part of a group suing Tyson for emotional damages.

“During the pandemic they supposedly recognized our work by putting a plaque on the front door saying ‘we are heroes,’“ said Maria Ruvalcaba, who has deboned chicken at the plant for over 16 years. “But now they are throwing the heroes away.”

Ruvalcaba and other workers at the Van Buren plant report that Tyson offered them a payment of $1,000 to stay at the plant until the day it closes, a 60% buyout of accrued vacation days, and an option to relocate to another Tyson facility. According to workers, the strike ended when Tyson made verbal commitments to the workers’ delegation to pay out all their vacation time, not increase employees’ workload before the plant closes, and address workers’ injury claims. Workers will still not receive the six-month severance packages they demanded.

Burleson said in an email that workers “with unused vacation or holiday time earned prior to the plant’s closing will be paid in full,” and that the company is offering “relocation assistance with financial incentives up to $15,000,” though he gave no further details. Workers at a Tyson plant in Glen Allen, Virginia, that’s also closing on May 12 were offered $15,000 in financial incentives over two years of continuous work for relocating to a Mississippi plant, and lesser financial incentives to relocate to plants in Virginia and North Carolina. However, the Van Buren workers Facing South spoke to said they were not made aware of any relocation incentives.

“We know clearly that Tyson has made a very considerable amount of money during the pandemic, many billions,” Ruvalcaba said. “And now they are using us again with even more pressure this time around.”

‘That’s all they know’

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The strike came together over the course of about two weeks, according to Magaly Licolli, the executive director of Venceremos, a labor justice organization in Northwest Arkansas that organizes poultry workers. Workers from the Van Buren plant got in touch with her to say they were thinking about direct action and wanted Venceremos’ help. Licolli met with the initial group of strike planners and then held two mass meetings, each attended by about 100 workers, by her estimate.

This was not the first time workers at Tyson’s Van Buren plant had tried to take collective action.

“They tried to organize before, during the pandemic,” Licolli said. “They thought that it was against the law, even, to have strikes.” Such misconceptions are not uncommon among workers in states like Arkansas that have anti-union right-to-work laws.

Many Tyson workers said they didn’t know about their rights until they started organizing and had meetings with Venceremos. For example, Edgar Cardenas said that in the 16 years he’s been with the company he didn’t know where or how he could report hazardous working conditions.

“In the time that I have worked for Tyson, I saw so many things that I didn’t know were against the law,” he said. “They were always hiding things from us by using different words.”

While there are supervisors there who speak Spanish, Edgar said he and many of his colleagues didn’t know about the existence of OSHA until they started organizing. Employers are required by law to post posters informing workers about their rights and responsibilities in the workplace, but they are merely encouraged—not required—to post Spanish-language signs in workplaces with Spanish-speaking workers.

Licolli said that once workers were assured direct action was not illegal, they decided they wanted to strike. “And I said, OK, if that is what you want, then I will support you in the process. We will bring resources, and we will form a legal team,” she said. “They were ready to hold Tyson accountable.”

The Van Buren strike follows another groundbreaking labor action by poultry workers on the industry’s home turf in Arkansas, the nation’s second-largest broiler-producing state. In December 2020, dozens of workers at a George’s processing plant in Springdale walked out of work to protest the company’s unsafe labor practices during the pandemic. Labor advocates said at the time that was the first such action they could recall by poultry workers in this part of Arkansas, one of the first states to pass a right-to-work law.

“Why aren’t there more protections in the South? Why aren’t there laws, policies, or someone to help us?” Recinos wondered. “There are protections for companies to keep their money. Why can’t we have the same rights in this state?”

The plant Tyson is planning to close in Glen Allen, Virginia, near Richmond, employs almost 700 workers. That plant is unionized with United Food and Commercial Workers Local 400, which released a statement calling the closure a “deep disappointment.” The union did not receive advance notice—just the minimum 60-day notice that federal law requires Tyson to give.

Despite the Glen Allen plant’s pending closure, Tyson is receiving more than $6 million in state incentives from Virginia to open a new plant about 150 miles away in Pittsylvania County, where some of the processing work will be automated.

“There’s a lot of people that have been there 30 or 40 years, and that’s all they know,” said Qiana Wilson, who has worked in a variety of positions over her 22 years at the Glen Allen plant.

Tyson offered the unionized Glen Allen workers an extra $1,000 to stay until the plant closes and a vacation-day buyout. It’s also offering them a relocation stipend if they transfer to another Tyson facility. Tyson has offered workers jobs at plants in Mississippi, North Carolina, and Virginia. If workers relocate to the Forest, Mississippi, plant—which is unionized with the Mid-South Council of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, an affiliate of the UFCW—they are eligible for a $5,000 initial transfer bonus after two months of work, a second $5,000 bonus after a year, and a third $5,000 bonus after two years of “continuous employment” at the location.

“Those are hours away,” Wilson said. “You literally have to go either stay for the whole week and come back on the weekend, or move.”

Like their counterparts in Van Buren, many of the Glen Allen employees have lived in the community for decades if not their entire lives, and moving would force them to leave their safety nets. But many lack skills easily transferable to other jobs, while others have chronic injuries from decades working in an unforgiving environment.

“The pain in my arms has become unbearable,” said Delgado, who is applying for disability rather than new jobs because of the injuries she sustained at Tyson. “They won’t employ me with both hands hurt. So I’m going to wait and see. Hopefully, with God’s help, something will be fixed.”

The Tyson workers have a strike fund, donate here.

Rachell Sanchez-Smith is a student journalist at the University of Arkansas and a producer/reporter at KUAF 91.3 Public Radio in Fayetteville. She formerly worked as a reporter and translator for Arkansascovid.com.

Olivia Paschal is the archives editor with Facing South and spearheaded Poultry and Pandemic, Facing South’s year-long investigation into conditions for Southern poultry workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.