‘Dirty Dozen’ Dangerous Employers Named for Workers Memorial Day

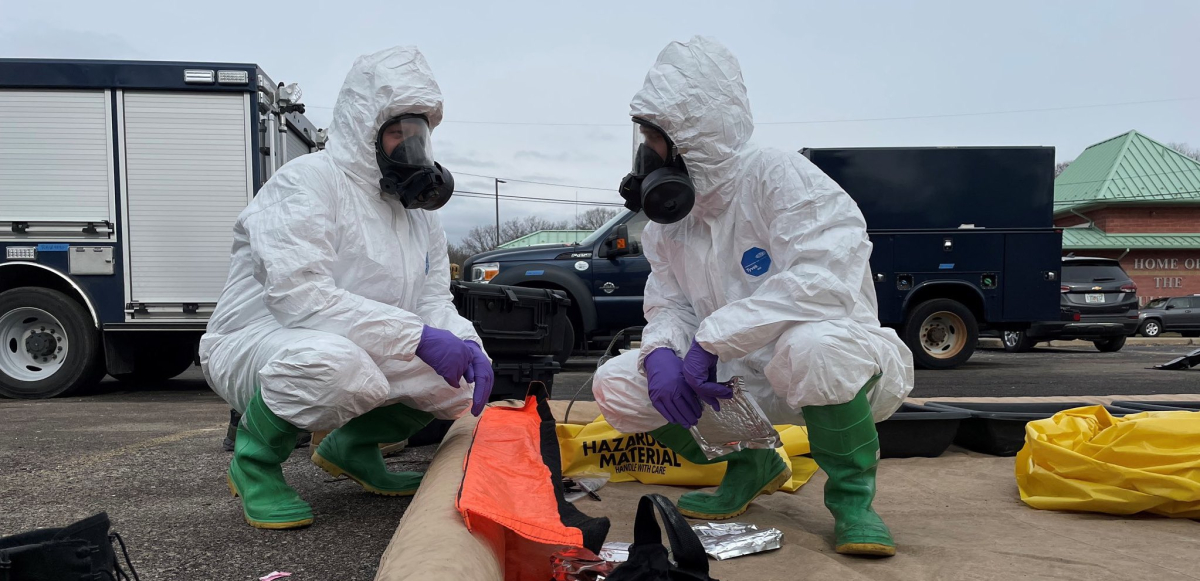

Members of the Ohio National Guard assess hazards in East Palestine, Ohio after a Norfolk Southern train derailed with tanks of hazardous chemicals. Derailments have become more frequent as the owners of big freight railroads cut back maintenance and run longer and heavier trains to pad profits. Photo: Capt. Jordyn Craft, U.S. Air National Guard (CC BY 2.0)

April 28 is Workers Memorial Day, commemorating those killed, sickened, or injured on the job. As part of a week of events, today the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health is releasing its “Dirty Dozen” report.

Here are four of the employers COSH has picked out for the “Dirty Dozen” distinction in 2023 because they run unsafe workplaces, endangering workers and the public: Swissport, Packers Sanitation, the Class I railroads, and FedEx. Some also have attempted to silence workers who speak up about hazards or are trying to organize a union to make the workplace safer.

Swissport International AG

“Being Sprayed with Poop Is Not in The Job Description,” read one worker’s hand-lettered sign at a February rally at New York’s La Guardia airport. Swissport workers at three U.S. airports walked out on December 8, protesting the company’s faulty equipment, unfair leave policies, understaffing, speedup, and resistance to the workers’ forming a union to address these problems.

Swissport International AG is a worldwide airport services and cargo handling company with 42,000 employees, half of whom work in the Americas. The company’s workers service airlines with baggage handling, refueling, deicing, emptying waste, and cleaning cabins. Swissport also operates 119 air cargo warehouses handling freight, mail, and specialty cargo like temperature-controlled medications and time-sensitive transplant organs.

But understaffing is leading to difficult working conditions and worse. Carl Rothenhaus, a cargo office agent at a Swissport warehouse at Boston’s Logan airport, said that sometimes they’re so understaffed and rushed that it endangers important cargo like lifesaving transplant organs that need to be shipped fast.

U.S. Swissport workers have been organizing a union with Service Employees (SEIU) Local 32BJ, but the company has been punishing union advocates, the workers say, despite the claim in its 2021 company report that it supports “freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining.”

At La Guardia, the company services Air Canada and Spirit Airlines. Workers there report that Swissport contracts for more work than it can handle, leading to severe understaffing, which then leads to aircraft scheduling delays for which the workers are blamed.

Workers drain toilet waste from passenger planes, which involves attaching a hose to the waste port. But old and broken equipment cannot be securely attached—so workers get soiled and sometimes drenched with the waste. Then they’re not allowed to take the time to clean themselves and change clothes; instead they are hurried on to other jobs, including cleaning the plane’s interior.

The cabin cleaning job is also rushed, workers say, with only time to remove trash and check the bathrooms. Short staffing means that baggage handlers have to work alone, leading to injuries. When injured or sick, workers in New York said, they are prevented from taking sick leave that they had accumulated—or punished by having their pay docked after they took sick leave they were entitled to.

Workers who speak up about problems have experienced discipline in the form of suspensions. Ramp worker Omar Ramirez was told by his supervisor to look for another job after he spoke to the press about his working conditions at La Guardia. The union filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board on behalf of workers at Newark Airport in New Jersey, alleging that managers “coercively interrogated employees who supported forming a union.”

At Logan airport, Rothenhaus said, workers and their supervisors have complained for years about worn-out, unreliable forklifts and inadequate staffing. The forklift issue was recently resolved, he said, but “when you don’t have the proper equipment or the people to do what your job is supposed to do, things can get dangerous.”

–Jenny Brown

Packers Sanitation Services

The meatpacking and poultry industries employ half a million workers, disproportionately immigrants and people of color. Their crushing toil puts them at high rates of amputations, broken bones, illnesses, and fatalities. Yet they earn piteously low wages—almost half are living in poverty, and only 15.5 percent are covered by health insurance.

Recently the Wisconsin-based company Packers Sanitation Services paid a $1.5 million fine for illegally employing 102 children to clean 13 meatpacking plants in eight states, according to the Department of Labor.

The children, including some as young as 13, handled dangerous chemicals to clean saws and head-splitters at plants owned by meat-processing giants JBS Foods, Tyson Foods, and Cargill.

A 13-year-old Guatemalan girl worked the night shift at a JBS plant in Grand Island, Nebraska, where she scoured “blood and beef fat from the slippery kill floor, using high-pressure hoses, scalding water and industrial foams and acids,” according to The Washington Post. A middle school nurse learned of her night job after finding “chemical burns, blisters and open wounds on her hands and one knee.”

In October 2022, the Department of Labor found 27 underage children at the plant. JBS has faced neither fines nor criminal penalties. The girl’s father was sentenced to one month in jail for driving her to work at JBS and faces deportation, while her mother has pleaded guilty to child abuse and faces up to one year in jail and the prospect of losing her meatpacking job.

Packers Sanitation, one of the country’s largest food sanitation companies, is owned by Blackstone, the world’s largest private equity firm. The company employs 17,000 workers at 700 sites nationwide.

–Luis Feliz Leon

Billionaire Bill Ackman, Norfolk Southern and Class One Freight Railroads

When railroad workers threatened to strike for the right take emergency time off for an illness in fall of 2022, they exposed the dangerous business plan of the Class One freight railroads they work for.

The federal government blocked the strike. In a compromise brokered by Congress, the railroads were apparently willing to increase pay—but they were not willing to let workers take unplanned time off the job, because they are running the system so lean that it is on the verge of collapse.

Class One railroads (BNSF, CSX, Kansas City Southern, Union Pacific, Canadian Pacific, Canadian National Railway) are the six biggest operating in the U.S., with annual revenue over $500 million.

Under a system known as Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR), the big carriers have increased the length and weight of trains, and cut staff by 30 percent in the last six years, at the behest of activist shareholder Bill Ackman and other railroad company owners who demand maximum returns.

The result has been a tripling of profit margins for the railroad owners over the last two decades, but devastation for communities like East Palestine, Ohio, which experienced a train derailment on February 3, including 11 tank cars carrying toxic materials. Leaking tanks containing vinyl chorine had to be burned off to prevent a toxic explosion. Two thousand residents were evacuated, and many report continuing health problems.

Jason Doering, a locomotive engineer based in Nevada and general secretary of the cross-union rank-and-file group Railroad Workers United (RWU), said there has been a recent increase in derailments due to PSR, which “prioritizes short-term financial gains for Wall Street over the safety of communities and railroad workers.”

In addition to riskier, heavier, miles-long trains, maintenance has gotten less attention, rail workers say. The East Palestine derailment was likely due to an overheated bearing on one of the train’s 149 cars. The overheating was detected by sensors along the route, alerting the train crew, but it was too late. Preventive maintenance could have caught the issue.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

That derailment got a lot of press attention, but major train derailments are now common. RWU noted that in just the last week of March there were six significant wrecks: 55 cars and two Union Pacific locomotives were destroyed in a wreck in the Mojave desert, 31 cars of a Canadian Pacific train derailed in North Dakota, a BNSF train derailed in Minnesota with ethanol cars catching fire leading to a local evacuation; 15 cars filled with ore derailed in Pennsylvania; 19 cars of a Norfolk Southern train derailed in Alabama; and 24 cars plunged into the Clark Fork River in Montana.

“These companies siphon billions into share buybacks, dividends, and bonuses,” said RWU Steering Committee member Paul Lindsey, a locomotive engineer based in Idaho, but at the expense of “vital maintenance and infrastructure.”

–Jenny Brown

FedEx

If the combination of short staffing and the pandemic shipping boom has made life hell for union workers at UPS and US Postal Service, imagine how much worse it is at nonunion FedEx.

Workers in its hubs race through the night loading and unloading planes and trucks and feeding fast-moving conveyor belts to meet overnight shipping deadlines. Supervisors routinely push them to work unsafely—for instance, sending one worker into a trailer to shift around heavy packages rather than wait for a team of three.

A steady drumbeat of grisly deaths on the job—especially at the company’s giant hub in Memphis—tells the story of speedup and corners cut.

In 2015, a man died crushed under a trailer at the Memphis hub.

In 2016, a package handler broke eight ribs and an arm and lacerated her liver when she was caught between a catwalk and a dolly. An investigation by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism and ProPublica found that Tennessee OSHA accepted the company’s own proposed remedy for that incident as sufficient: FedEx said it would do safety trainings.

In 2017, a worker died there on Thanksgiving after she was hit by a cargo loader and dragged under a conveyor belt. This time Tennessee OSHA citied the company for a “serious” violation—and fined it a measly $7,000.

In 2019, a worker was killed when a container door swung open and slammed him into a metal pole. Again the fine was $7,000—later reduced to $5,950, MLK50 and ProPublica found.

And last year, a worker driving a forklift struck a damaged part of a ramp; she was ejected from the forklift and crushed to death under it. She had complained about the dangerous condition of the ramp, an uneven metal grating. “She told me that they had a meeting and said they could not afford to fix the ramp,” her mother told MLK50 and ProPublica. “I guess if they say all they got to pay if somebody dies is $20,000, they come out cheaper keeping the ramps.”

And that was only one of three deaths in workplace incidents at the Memphis hub last year. Across workplaces, FedEx’s latest available “Global Citizenship Report” shows seven to 10 fatalities on the job each year. Among them were a man crushed by a falling pallet in a trailer in North Dakota, a man who fell between two trucks during extreme cold weather in Illinois, and a worker repairing a plane who was crushed when a landing gear door automatically closed on him in Texas.

In all, the company has been dinged $9,185,224 for 235 safety-related offenses since 2000, Good Jobs Tracker reports, including $7,990,450 for 137 aviation safety violations.

This appalling record shows what kind of enforcement former president Donald Trump was going for when he tried to appoint FedEx Ground’s former safety head, Scott Mugno, to head the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Mugno had lobbied to increase the national weight limit on trucks, and allegedly retaliated against workplace safety whistleblowers at FedEx. Pressed by Sen. Patty Murray to name any rule proposed by OSHA that he had supported during his entire career, he couldn’t come up with an answer. The Senate never confirmed him.

FedEx has managed to keep its various workforces mostly nonunion so far, including by misclassifying delivery drivers as independent contractors and spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on anti-union consultants. An experienced FedEx Ground driver today is making less than half what an experienced UPS delivery driver makes, the Spokane Spokesman-Review found—it’s $20 an hour with no benefits at FedEx, compared to $42 plus health insurance and a pension at UPS.

Could a national UPS strike this summer, combined with the national attention to grassroots organizing drives at Amazon, inspire FedEx workers to renew their union efforts? They certainly need it.

–Alexandra Bradbury