Striking Alabama Coal Miners Want Their $1.1 Billion Back

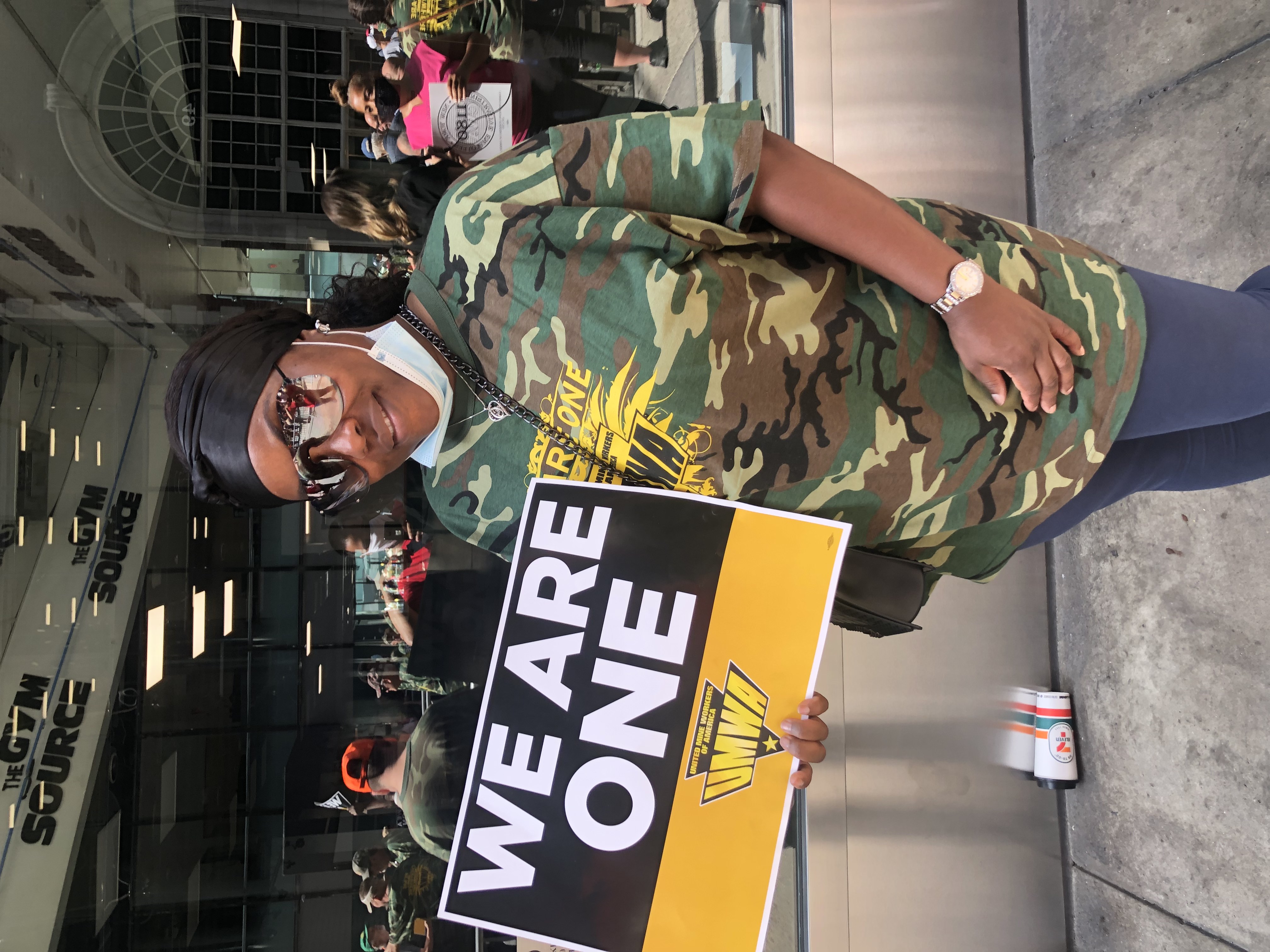

Eleven hundred miners have been on strike against Warrior Met since April 1. They made massive concessions in 2016 to keep their employer solvent. Photo: UMWA

History repeated itself as hundreds of miners spilled out of buses in June and July to leaflet the Manhattan offices of asset manager BlackRock, the largest shareholder in the mining company Warrior Met Coal.

Some had traveled from the pine woods of Brookwood, Alabama, where 1,100 coal miners have been on strike against Warrior Met since April 1. Others came in solidarity from the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania and the hollows of West Virginia and Ohio.

Among them was 90-year-old retired Ohio miner Jay Kolenc, in a wheelchair at the picket line—retracing his own steps from five decades ago. It was 1974 when Kentucky miners and their supporters came to fight Wall Street in the strike behind the film Harlan County USA.

“Coal miners have always had to fight for everything they’ve ever had,” Kolenc said. “Since 1890, when we first started, nobody’s ever handed us anything. So we’re not about to lay our tools down now.”

The longest that miners ever went on strike was for 10 months in 1989 against the Pittston Coal Company in West Virginia, defending hard-won health care benefits and pension rights. Some 3,000 miners got arrested in that strike. AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, who passed away on August 5, was president of the Mine Workers (UMWA) at the time.

In Manhattan, mixed in the sea of camouflage T-shirts outside BlackRock was a smattering of red and blue shirts—retail, grocery, stage, and telecom workers. The miners and supporters circled the inner perimeter of four police barricades, chanting “Warrior Met Coal ain’t got no soul!” and whooping it up.

Postal and sanitation trucks honked in solidarity. “You’re in New York City,” Mine Workers President Cecil Roberts told the crowd. “When somebody comes by driving a trash truck, they’re in a union. Chances are, somebody comes along with a broom in their hand, they’re in a union.”

‘WHERE’S OUR MONEY?’

The strikers are fighting to reverse concessions that were foisted on them in 2016 when newly formed Warrior Met Coal bought two mines and one preparation plant from Jim Walter Resources during bankruptcy proceedings. BlackRock became one of the three majority shareholders in the new company.

Since then, the union calculates that workers have forked over $1.1 billion in pay, overtime, vacation, safety, health care, and other benefits to help the company regain solvency. Today 26 hedge funds have investments in Warrior Met stock, signaling their confidence in its profitability.

“We want everything back. And then some. That’s the message we’re trying to send to BlackRock,” said Michael Wright, a miner for 16 years.

Warrior Met produces coal used in steel production in Asia, Europe, and South America. In response to the strike it has scaled back production, left one mine idle, and stopped stock buybacks, Bloomberg reported. The strike has cost the company $17.9 million, according to its second-quarter earnings report.

Shortly after the miners walked out, management returned to the table with an offer that would have recouped just $1.50 of the $6 cut in wages from the 2016 contract and left intact punitive disciplinary policies and benefits concessions. The miners voted it down, 1,006 to 45.

“We come back to the table and they’re offering less what we were making originally,” said Brian Seabolt, another 16-year coal miner.

“We go underground to sacrifice our lives for our families,” said Wright. “They’re making billions of dollars. Where’s our money?”

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink has burnished his public image as a benevolent capitalist concerned about climate change and social justice. The strikers hope to gain leverage by tarnishing that image.

BlackRock has a shield that makes that harder: two-thirds of its investments are in index funds, passively managed portfolios that bundle together investments regardless of social impact.

But it’s even harder to hit it hard enough in the pocketbook to have an impact: Warrior Met makes up just a tiny fraction of BlackRock’s portfolio. The asset manager had a record $9.5 trillion in assets under management at the end of June.

Nonetheless, to hurt profits, strikers were blocking scabs from entering the mines—until the company obtained an injunction to stop them. Despite that, the mines produced only 1.2 million tons of coal during the second quarter—a million less than the same period last year.

A GRUELING JOB

Another striker on the Manhattan picket line was Tammie Owens, a former steelworker. She switched to mining because it had better pay and benefits, though the job was grueling. “And then a few years later, I ended up with worse benefits than what I had at the steel plant,” she said.

Since the strike, she has picked up a side job to provide for her family. The union has also distributed $4.3 million to miners to cover health care.

Besides pay and benefits, the 2016 concessions included a punitive attendance policy that one miner’s wife described to journalist Kim Kelly as “four strikes and you’re out.”

“If I had a heart attack, they can give me a strike,” Owens said. “They don’t accept a doctor’s excuse. Even if I have something contagious that I can give to other people—pneumonia, the flu, strep throat, you name it—you have to come to work.”

Excessive overtime is another flashpoint (shades of Frito-Lay and Amazon). Miners have been forced into 12-hour shifts stretching into weekends—without the double pay on Saturday and triple pay on Sunday that they used to get.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

And health care looms large. Costs shot up; the company now covers only 80 percent of the premium. “We need 100 percent,” said miner Dedrick Gardner. “Considering the work conditions in a coal mine, health care is vital. You’re dealing with silicosis, black lung, diesel, smoke.”

Black lung is caused by breathing in coal dust. The dust silts up the lungs, scarring and destroying them.

“Health insurance went from $12 for seeing any doctor in the world to $1,500 family deductible and co-pays up to $250,” said Local 2245 President Brian Michael Kelly.

TOXIC AND DANGEROUS

Safety is a perennial concern. “I work 2,200 feet underground in one of the most gaseous mines in the world,” Owens said. “If something goes wrong, it could blow the top off the ground.”

In 2001, 13 workers died at one of the mines now owned by Warrior Met after a slab of rock fell and set off a methane gas explosion, burning and pounding miners to death with chunks of rock.

Despite that tragedy, the 2016 contract eroded safety standards. And the situation is presumably even worse for the scabs inside now.

“Nonunion mines are continuously known for cutting corners and creating unsafe working environments in order to increase production,” said union spokesperson Erin E. Bates via email. “Warrior Met Coal is currently mining and processing coal with unskilled workers. We are concerned it is only a matter of time until someone gets seriously hurt.”

Without the union watchdog, apparently the company’s environmental practices slipped too. Shortly after the strike began, wastewater from one of the mines suddenly turned local creeks black with pollution.

What’s the Future of Coal Mining?

The UMWA has seen the writing on the wall and has outlined energy transition goals intended to preserve coal jobs and communities, while also creating new jobs.

The first part includes trade policy and steel production. The union calls for “creating incentives to bring basic steel and other metals industries back to U.S. shores to enhance metallurgical-grade coal production and energy demand.” In 2018, President Donald Trump imposed tariffs of 25 percent on imports of steel and 10 percent on aluminum. True to form, Trump exaggerated the impact of the tariffs: domestic prices shot up at first, then fell back down.

While a revival of the metallurgical coal used in steel production could offer leverage to the miners in Alabama—Birmingham’s steel industry once earned it the nickname “the Pittsburgh of the South”—it would be insufficient to save the jobs of miners elsewhere in the U.S., since the biggest use of coal is to generate electricity.

Since 2011, as calls have grown more urgent to reduce the greenhouse emissions that cause climate change, the industry has hemorrhaged 41,000 jobs—the product of bankruptcies and of emissions-heavy coal losing out to fracking and other energy sources.

A CARBON-CAPTURE FIX?

The Mine Workers’ proposal, launched alongside the Congressional debate over an enormous infrastructure package, calls for research into carbon-capture technologies that store carbon dioxide underground. Coal is the single largest source of energy-related carbon emissions.

Carbon-capture has the backing of some of the world’s largest oil and gas companies, and of politicians who view it as a painless panacea. But the science of whether it will work is hotly contested even among climate scientists and unions.

Trade Unions for Energy Democracy characterizes carbon-capture technology as providing “cover for new coal infrastructure” and worsening “the environmental damage associated with extracting, transporting, and burning.” TUED proposes public ownership to reclaim energy sources instead of market-based solutions.

The UMWA proposal also calls for good jobs and tax credits to incubate the production of solar panels and wind turbines, key components of the clean energy portions of the infrastructure bill.

At the New York picket line, UMWA President Cecil Roberts said the union is working with the government to bring two-thirds of the solar panels and turbines currently produced in China to the U.S.

But he declined to call these efforts a just transition, since they would still fall far short of replacing the jobs lost. “Most people in the coalfields believe that they’ll see the second coming of the Lord before they see a just transition,” Roberts said.

TEMP JOBS WON’T CUT IT

The skepticism is warranted. President Joe Biden has put up a $16 billion proposal to clean up abandoned oil and gas wells—mine reclamation, the UMWA’s proposal calls it. The U.S. Department of Commerce has committed an additional $300 million in funds, according to a Reuters article.

But what does that amount to in workers’ wallets? Reuters interviewed a 68-year-old in Virginia who was getting just $17.50 an hour to clean up an abandoned mine—significantly less than he made over decades as a miner.

These lower-paid, temporary cleanup jobs won’t bridge the chasm dividing mining communities from a green energy future.

“The only way to fully replace jobs that are at risk is to establish major manufacturing centers in coalfield areas that will employ hundreds at a time for decades, not dozens at a time for four to five years,” UMWA press secretary Phil Smith told Reuters.

Of all the picketers I met in New York, one had the biggest stake in those future jobs: 12-year-old Marco Mijangos. He travelled from West Virginia with his grandfather to support the striking miners.

Working in the bowels of the Earth “is one of the most dangerous jobs in the world,” Mijangos said. “And not getting the fair wage you deserve, it’s just sad. Some people can get a better job sitting in an office all day than mining coal.”

Which job does he envision for himself someday? “I sure want to be in one of those offices,” he said. “But if I must, I will be down there.”