Make Workplace Mental Health a Priority, Says Union President Who Survived San Jose Shooting

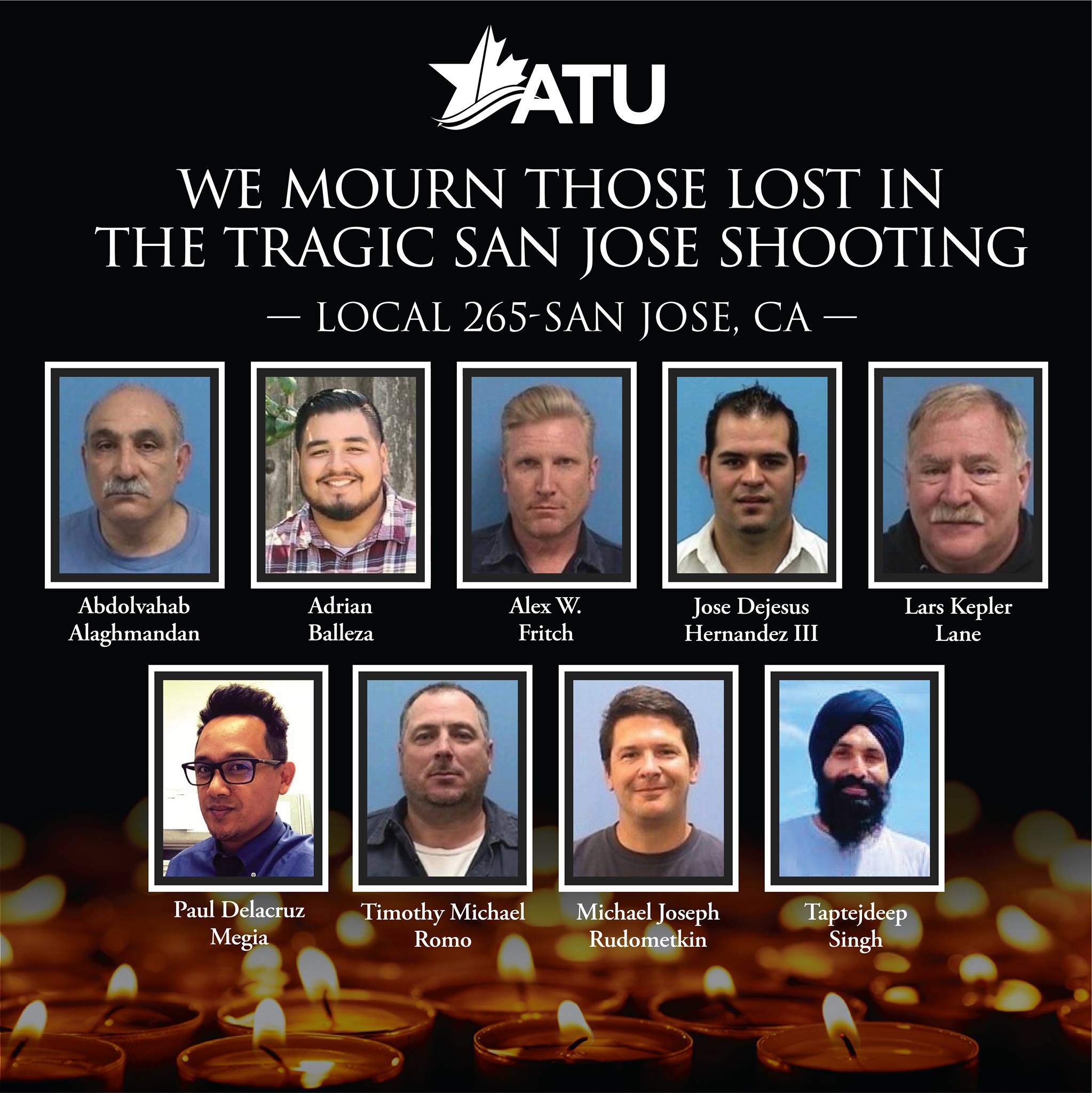

Mourners set up a vigil outside San Jose City Hall for the nine union members killed in the May 26 shooting at a Valley Transportation Authority light rail yard.

It was 6:30 a.m. and workers at a San Jose light rail maintenance yard were talking with their union president during shift change.

Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 265 President John Courtney was there to discuss the state of the union, including a campaign for hazard pay and management’s push to squeeze more passengers onto buses and trains despite Covid. “You can’t run a union from your office,” Courtney says. “You have to get out there amongst the people. You have to hear what they have to say. They have to hear what I have to say.”

Minutes into the impromptu May 26 meeting, six union members were gunned down before his eyes. Another three were killed elsewhere in the yard—victims of the deadliest mass shooting in Bay Area history.

PANDEMIC BATTLES

Santa Clara County, where San Jose is located, had been the site of the first Covid death in the U.S., on February 6, 2020. The local has spent the pandemic battling the Valley Transportation Authority over safety and scheduling.

One big fight was for rear-door boarding, which meant suspending fare collection. The VTA did it early in the pandemic, on March 19, after bus drivers reported that passengers were doffing their masks to talk or lingering up front while they paid. Courtney credits the policy with keeping Covid numbers low among Local 265 members, at first.

But last August, the VTA switched back to front-door boarding and collecting fares. “Social distancing was respected everywhere else—Walgreens, Rite-Aid, supermarkets,” says Courtney, “but when it came to our buses, they wanted to eke as much money as they could out of a worldwide pandemic.”

Another recurring fight was over how much social distance workers and passengers must maintain; VTA kept trying to reduce it from six feet to three. It rankled members that these decisions were being made by managers working from home. “There was this whole double standard of management making all these decisions about transit from the comfort of a couch,” says Courtney. “How easy is it to say you can cram 25 people into a bus? As long as you’re not on that bus, I guess it’s okay.”

CAUGHT COVID AT WORK

Soon, the Bay Area and the whole country saw an uptick in cases. Last August the local suffered its first death, a driver named Audrey Lopez.

“She was very cautious about Covid,” said Courtney. “She would wipe her bus down. She even had food ordered to her house because she was afraid of getting Covid in a supermarket.”

And yet when Lopez got sick, the company tried to deny her workers’ compensation: “They still continued to fight whether or not it was work-related, when all she ever did was work,” Courtney said. “That was the last straw.” Lopez’s death was eventually deemed a work-related injury.

The local also fought to make sure workers could stay home while sick or waiting for Covid test results, without getting hit with attendance “points” or burning through vacation time.

Of the local’s 1,500 active members, 185 had tested positive by February 2021, when the VTA finally restored rear-door boarding under pressure from the union and threats by rank-and-file members to stop front-door boarding on their own.

‘A LITTLE BIT OF BITE’

Courtney became president just before the pandemic started. He has been at VTA for a decade, and before that, honed his combative style as a steward and business agent with Transport Workers Local 234 at SEPTA in Philadelphia: “I like to say we have not just a bark, but a little bit of a bite.”

Courtney has fought to stop contractors from doing union work and to get safety barriers installed to protect drivers from assault by passengers (an ongoing battle, though one that's seen some progress). He emphasizes the organizing role of rank and filers and stewards, emphasizing the importance of empowering them by "making sure they know the leadership has their backs." He’s a familiar face among maintenance workers, and he’s pushed to make sure they are included in meetings with upper management, “so the maintenance workers have a voice in the way that things are done in their workplace.”

“The union movement is fighting for rights, and it doesn’t ever end—it’s every minute of every single day,” says Courtney. “We can’t just roll over—we have to question [VTA’s] authority at every single turn, because with a void of leadership, the company will fill that void with what they want, irregardless of our rights.”

Earlier in the pandemic, the union had pushed to put more buses on the road to avoid passing up riders when buses were at maximum capacity (reduced because of social distancing). To identify the routes where buses were needed, Courtney analyzed recordings of drivers’ calls alerting the control center of pass-ups—something management never thought to do.

“It was easy for me to do, so it should have been easy for them to do,” he said. “But they didn’t see it until the union presented it to them. And then they claimed, ‘We don’t have enough buses, we don’t have enough drivers,’ but the fact is they did.” Eventually the union won.

‘THINK THEY KNOW BETTER THAN WE DO’

In May, as the pandemic seemed to be ebbing, management announced it was reducing social distancing to three feet.

Courtney’s response, in a May 21 statement, highlighted how workers and riders had won safety gains throughout the pandemic, and how they were still fighting to restore service to pre-pandemic levels.

“One thing we have learned is that a small group of political elites and technocrats—people who have weathered the pandemic in the safety of their homes—think that they know better than we do when it comes to the transit we need and deserve,” Courtney said in the statement. He also noted that VTA’s “lip service to the heroism of our frontline transit workers still has not translated into any kind of hazard or hero compensation”—an issue the union has raised since the start. (See box.)

FATAL MORNING

Five days later Courtney woke up early, determined to talk with members about these issues.

“I knew I wanted to go out to the property. I didn’t know where I wanted to go.” But after 18 years working on subways and trains in Philly, light rail maintenance was where he felt at home—so that’s where he headed.

Courtney parked his car and walked into the yard. He chatted with a couple of track workers. As he headed into the building, he saw maintenance worker Sam Cassidy, a 20-year union member, fidgeting with something in his hand.

Courtney thought it might be a radio. “I said, ‘Hey Sam,’ and he acknowledged me, but I couldn’t see what was in his hand.”

Courtney headed for a small room where substation maintainers and overhead line workers often gather. “It wasn’t even a union meeting,” he said. “Just communicating to the members. If they saw me they would come by—nothing out of the ordinary, something I always do.

”I sit down and I start talking to some of the guys that are in the room already. And then some more people join us. Then the killer appears in the doorway. It was kind of unusual—he had his mask on really tight.

“He says, ‘What’s up with this whole management working from home, making all these decisions, and we’re out here on the front line? What are you gonna do about that, John?’”

“That’s always been my thing,” Courtney said. “It just so happened that the day before, I had a conversation with the general manager. They wanted to increase capacity on buses, they kept testing the waters to see if they could get me to bend on that or even test the county’s regulations. I told the general manager how there’s no respect for management when you’re making these decisions from your couches.”

Cassidy shook his head: “He kinda was like, ‘OK, good answer.’ It’s a truthful answer.” Courtney then started talking about some local politicians. Seconds later, the shooting started.

The gunman fired more than two dozen rounds in that room alone. In the end he fired 39 bullets, using the last one to take his own life. Eight members of Local 265 were killed, along with a member of AFSCME Local 1101. They ranged in age from 29 to 63.

Courtney was spared. In the midst of his shooting spree, Cassidy told him, “I’m not going to kill you.”

‘WORDS DO NOTHING’

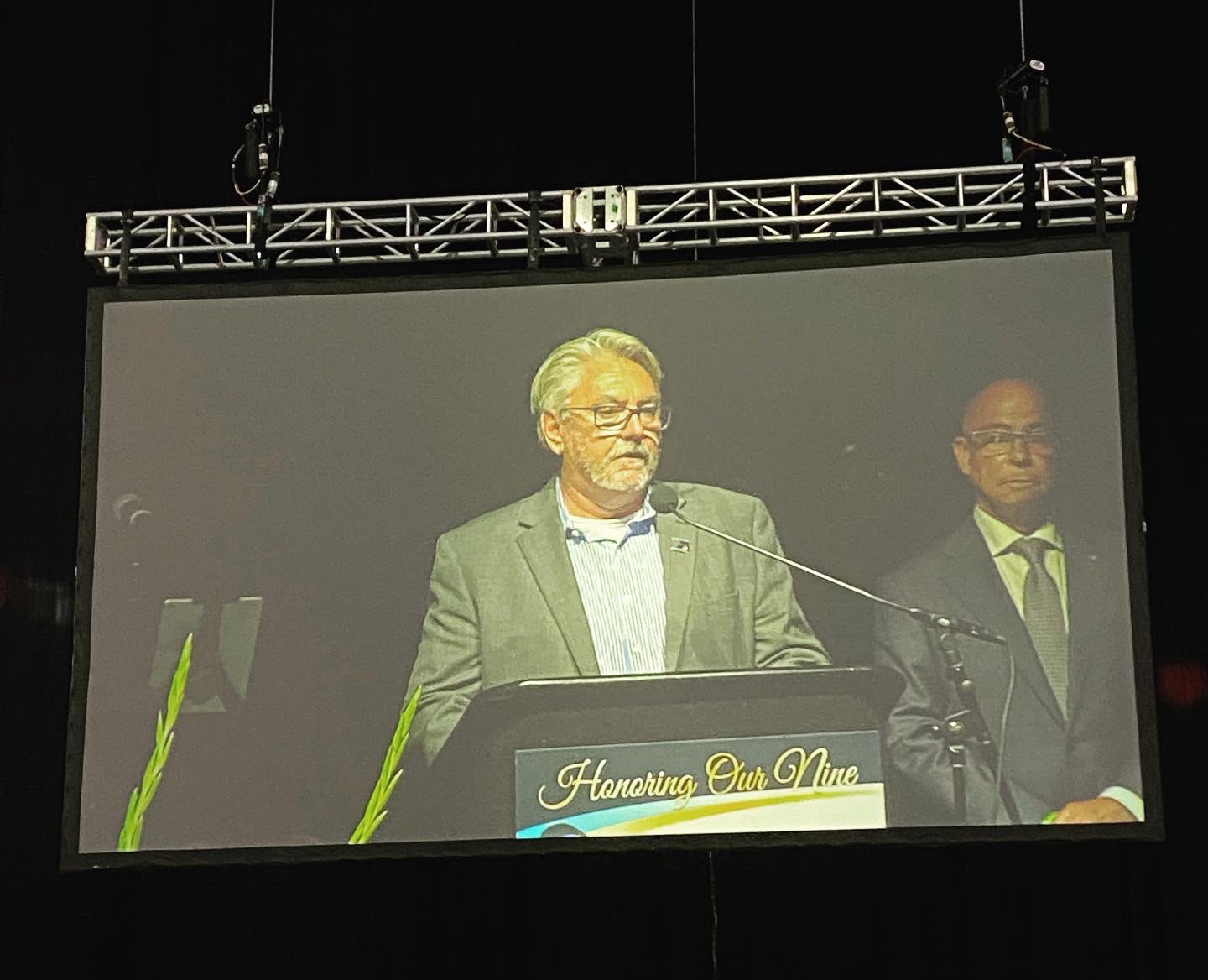

At a July 18 memorial the VTA held for the nine fallen union members, Courtney told the crowd, “If we don’t do something about the way VTA management handles our people, nothing will change.” That line drew applause in an otherwise somber event. (See a video of the event compiled by ATU here.)

Courtney—whose name had been left off the program until the night before (“Who here thinks that was an accident?,” he asked the crowd)—was frustrated that the authority had refused to remove light rail management, pending an investigation into the work culture there.

“What I meant by that was that the same folks were gonna run the show when they brought light rail back,” Courtney told Labor Notes. “The managers knew that there were problems. I don’t mean problems about the killer—just general problems that could lead to a mentality in the workplace where the workers feel that no one cares about them, that they don’t care about our safety.

“A simple example: we had a dump truck that needed a seat, because the springs were so bad that if you drove it, you felt like you were gonna break your back. The guys requested a seat or a new truck for almost a year, and they got nothing.”

He was furious with VTA’s callous response to the shooting, and that they had immediately cut off benefits for the nine murdered members. When union officers met with the agency’s interim manager about time off for traumatized members, Courtney was “flabbergasted” at management’s seeming eagerness to rush people back to work.

Another Tragic Loss

Today (August 17) ATU reported that Local 265 executive board member and paint and body worker Henry Gonzales tragically took his own life. Gonzales also worked in the VTA light rail yard and survived the May 26 shooting.

In a statement, ATU International President John Costa said, “This tragedy once again underscores the need to make mental health a priority in the workplace. Unfortunately the VTA has taken no action to address the grief, the mental health, and the safety of employees who have been under unfathomable, extreme stress after this tragic shooting. The VTA’s inaction is shameful and threatens the well-being of our Local 265 members. VTA workers must have immediate access to the full spectrum of mental health services, including in-patient care. They must also have access without having to get through the thicket of bureaucratic hurdles that currently restrict access to needed care.

“Now more than ever, the ATU is committed to advocating for the mental health care of our members. We must make mental health a priority in the workplace, not just after a tragedy. We have to end the stigma around asking for help. We vow to continue to do what the VTA has failed to do in memory of Brother Gonzales and our nine brothers killed that day.

“If you need help, please don’t hesitate to reach out. We urge our members who are dealing with mental health concerns or substance abuse to contact our trusted partner, FHE Health, at 1-866-276-1610.”

“Our folks are driving around a 40-foot or a 60-foot bus,” Courtney said. “If you’re grieving and you don’t have the proper time to grieve, then you’re driving a missile—because you’re in your head, you’re not thinking about how this is unsafe.”

“Words do nothing,” Courtney said at the July 18 memorial. “The actions speak volumes. To this point from that tragic day there have been no real substantive changes. That is not how you honor nine brothers who gave their lives to the company. It takes courage to make real change. We expect courageous actions from the Board, from supervisors.”

MENTAL HEALTH BREAKS

What can we learn from this tragedy? Courtney wants mental health to become a priority in the workplace.

That means something other than the Employee Assistance Programs that the VTA and many other companies have, where the employer sponsors free counseling.

“Most of our employees don’t want to go there because it’s company-oriented,” Courtney said. “We don’t know how much information’s getting shared—probably none, but we’re suspicious.”

Instead, he wants a resource that the agencies work with the unions to set up, so the unions can vouch for its confidentiality. “Maybe once in everybody’s career you can have a 30-day reset and go into a place that deals with your mental health and get it right before you come back,” he said.

“I also want to have a place where we can safely take a member who we may or may not think is having problems, to develop tools where we can approach these members—without insulting them, without disrespecting them—where we as shop stewards can walk up to them and say, ‘Hey, I noticed your day’s a little off today. Can you talk?’

“We just need mechanisms in place that recognize the need for mental health. Especially in our industry—people stay on the job for 30 or 40 years, they want that pension. In a lot of cases they’re driving for 12 hours a day. So unless they’re machines, they need some mental health breaks.”

That goes for Courtney himself. He’s been diagnosed with severe post-traumatic stress disorder and is now in Florida receiving inpatient treatment.

“I thought I could carry the weight of my family, ATU Local 265 members, friends, and many others affected by this disgusting act of violence,” he wrote on Facebook. “I was wrong… It is ok to not be ok, and there is nothing wrong with admitting you need help.”

CORRECTION: This article has been updated to reflect that one of the nine workers killed, Paul Megia, was a member of AFSCME Local 1101.

HAZARD PAY PUSH

Transit workers—like other workers deemed essential—put their lives on the line by working through the pandemic. Bus drivers took on the high-stakes new responsibility of enforcing county and federal mask-wearing ordinances.

Concerns about the virus followed them home. “In a lot of cases our folks were coming home, undressing, throwing their clothes right into the washing machine before they even got into their house, taking a shower,” Courtney said. And even so, “the whole time you’re wondering if you had brought Covid to your family.

“Some of our folks, their parents or elders have passed away because of Covid, and to this day in the back of some of our drivers’ minds is ‘Did I kill my father?’ Those are the types of things we had to deal with.”

These are among the reasons why the union is still pushing for hazard pay. “They have the money,” Courtney says: VTA just got $55 million released from the American Rescue Plan Act (money the union and transit advocates had been pushing to unlock for months) and expects millions more in the future.

Other transit locals in the area share the same demand, and the pandemic has bred greater collaboration among them. Leaders of California ATU locals meet weekly (virtually) and so does a Bay Area Blue-Collar Task Force that adds Transport Workers and Teamsters.

Members of sister ATU locals have been backing each other up by turning out to public meetings and bargaining sessions of the various transit agencies. On July 28 half a dozen Local 265 members came to an AC Transit board meeting to support dozens of ATU Local 192 members in a push for hazard pay there. AC Transit negotiators are set to meet with Local 192 about the issue.

Then Local 192 members turned out in solidarity to the VTA board meeting on August 5, where 20 members of Locals 265 and 192 raised hazard pay in the public comment session before VTA's board chair cut off comment.

In addition to recognizing the role of transit workers, Courtney hopes the importance of public transit as a whole will be recognized more widely after the pandemic: “What I hope for is to reestablish transit as it should be—a way to help with the environment, to help with congestion on the highways.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.