Teacher Strikes Boost Fight for Racial Justice in Schools

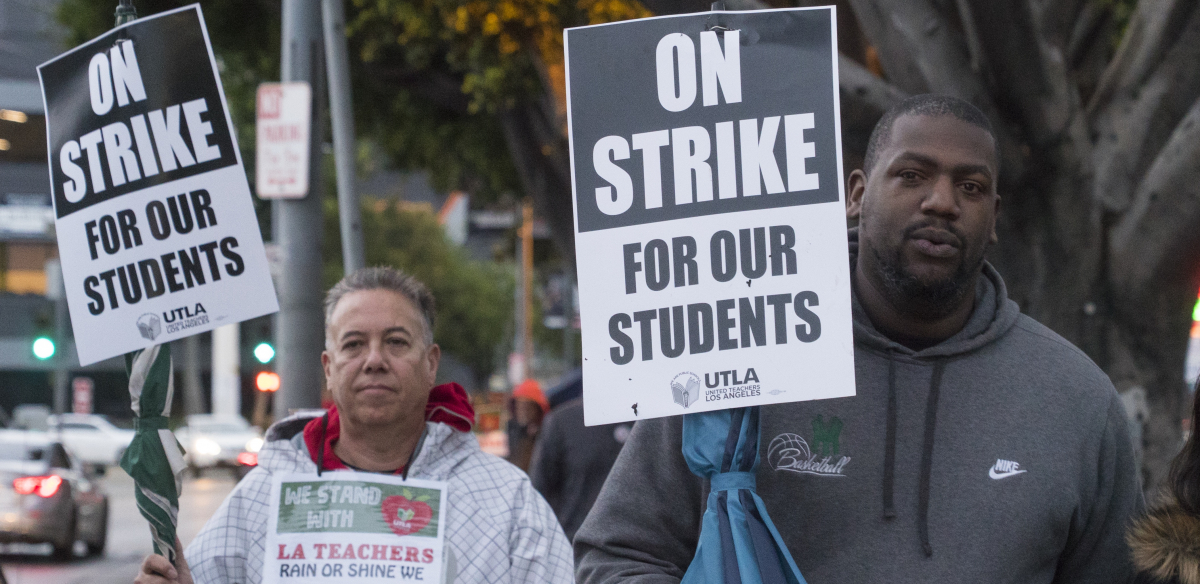

In the wake of last year's strike by Los Angeles teachers, random searches of students are coming to an end districtwide—landing a blow against racism in the schools. Photo: Joe Brusky, cropped from original.

One year ago, Los Angeles teachers on strike were demanding an end to random searches where students were yanked out of class to be frisked. By the time they walked back into work, they had won a partial victory.

Now these searches are coming to an end districtwide—landing a blow against racism in the schools.

L.A. teacher union activists, like their counterparts in Chicago, Seattle, St. Paul, and other cities, are making contract demands to confront segregation, underfunding, and the criminalization of the students they teach—problems that hit Black and Latino students hardest.

The L.A. strike elevated a wide range of demands, including smaller class sizes and more nurses and social workers. After listening to students about their top concerns, strikers highlighted the issue of random searches.

The district started this practice 30 years ago after a school shooting, with the stated goal of keeping weapons out. But as of 2019, L.A. was one of very few districts using random searches—only 4 percent do nationwide.

Students are pulled out of class while administrators and security officers search their bags and scan them with a metal detector. When these staff are short-handed, teachers and counselors are sometimes asked to do the wanding.

NOT SO RANDOM

A University of California Los Angeles report on two years of searches (2013-2015) found that they confiscated overwhelmingly ordinary items, not guns and weapons. Contraband included markers, highlighters, Wite-Out, lighters, and body spray.

And the “random” searches weren’t so random. The student-led group Students Deserve, which also includes parents and teachers, reported that students in magnet schools and advanced classes were rarely searched. Black students got searched most often.

Students said it made them feel like suspects at their own schools. Marshé Doss, a senior at Dorsey High School during the strike, had been searched and had her hand sanitizer confiscated; a school official accused her of bringing it to school to get high.

“As Black and Brown students, we have all of these things piled up against us,” said Doss. “I had so many questions after that experience.”

Teacher Sharonne Hapuarachy sponsors the Students Deserve chapter at Dorsey High. When the random search happened in her classroom, she was shocked. “It was really disturbing and scary for me, even as the teacher,” she said. She was taken aback by the way the students were spoken to. “It felt very serious; it creates a sense of anxiety.”

MADE THEM BARGAIN

Ending random searches was one on a long list of union demands that the district did not legally have to bargain over. The district ignored these—until the walkout.

“Because the strike brought out public opinion in support of our issues,” said United Teachers Los Angeles Secretary Arlene Inouye, “we were able to leverage that at the end to get things we would never get before.”

In the deal that ended the strike, the district committed to a pilot program, letting 14 schools apply to opt out of the searches right away; 14 more would become eligible two years later.

Other union wins were class-size caps, more staff, legal support for undocumented students, and green space on school campuses.

But the strike momentum led to a bigger win on the issue. In May, a school board seat opened up. With UTLA’s help, a union ally won the seat. And in June, the board voted to sunset the random searches with the end of the 2019-2020 school year.

JOINED STUDENT ACTIVISTS

Four years before the strike, teachers came to union leaders complaining about the searches, Inouye said.

She recalled one teacher in particular who brought the issue to her attention. “He never thought that the union would be interested in the issue,” Inouye said. “Of course we would,” was the leaders’ response, she said, “but we have to build and organize around it.”

Teachers and counselors said when they were asked to conduct the searches, it broke the trust they were trying to build with students. They also argued the searches were a waste of time that could be spent learning.

So UTLA teamed up with Students Deserve and the American Civil Liberties Union to launch the Students Not Suspects campaign. They organized forums and protested at school board meetings. High school students designed and handed out 18,000 #studentsnotsuspects buttons. Students and parents spoke up about why searches weren’t making schools safe.

“We fear it [being stopped and searched] outside of school,” said Amee Monroy, a Students Deserve activist who is a Dorsey senior this year. “We shouldn’t have to fear it in school.”

Students had been organizing on this issue since 2016. But “having UTLA on our side added way more people to the movement,” Monroy said. And the strike added big leverage.

COUNSELORS NOT COPS

L.A. teachers aren’t alone. The Chicago Teachers Union has been outspoken about the racism of that city’s school system.

Schools with many students of color are disproportionately deprived of funding and staffing. And before their 2012 strike, Chicago teachers battled a wave of school closings in parts of the city where the district should have been adding resources, not subtracting them.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

When Seattle teachers struck in 2015, they demanded funds and training for every school to form an equity team, which would identify and change racist discipline policies. They won these teams in 30 schools.

A central demand in St. Paul teachers’ near-strike in 2016 was alternatives to harsh discipline practices that disproportionately affected students of color. They won it.

In 2017, teacher activists in Philadelphia and Seattle first organized a week of action on the theme Black Lives Matter at School. Since then, a growing number of unions and grassroots education activists around the country has participated every February. One united demand is to end “zero-tolerance” discipline policies that impose mandatory suspensions or push students into the criminal system for certain infractions.

Students on Strike

Dorsey High School students who were active in the Students Not Suspects campaign supported UTLA’s six-day strike in 2019.

The district was trying to keep schools open during the strike, but student activists encouraged their peers to increase the pressure by not attending school.

Instead, 150 students attended a block party nearby. They made art and played music, then headed over to the school board for a protest and sit-in to show their support for striking UTLA members.

Students from different schools joined candlelight vigils and protests at the superintendent’s Malibu mansion and at school board members’ houses, demanding that the board meet the teachers’ demands and end the strike.

For Amee Monroy, an 11th grader at the time, a standout moment was joining 40,000 UTLA members and supporters in an enormous march through downtown L.A. despite pouring rain.

“I will always think about holding my umbrella and being in a sea of red,” she said. “It was so fun, and we were making change at the same time.”

Many school districts have moved to limit suspensions. But unions assert in bargaining that it’s not enough just to change the rules. What students need instead is more time and attention from trained adults; districts have to put money into staffing.

Last fall, teachers in Chicago made racial justice demands again when they walked out for 11 days. On top of guaranteed nurses, counselors, and librarians in every school, they proposed that the district allow high schools to reduce the number of police officers stationed inside and redirect that funding to hire staffers trained to counsel students.

They also demanded that the district stop cooperating with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and with the city’s police database of gang members.

A LEARNING PROCESS

CTU has protested the decline of Black teachers in the district—from 40 to 20 percent in two decades. It calls for the district to create pipelines to train and recruit teachers of color.

The union works in coalition with police accountability groups. When the city says there’s no more money for schools, teachers point to its creation of a $95 million cop academy.

All this action for racial justice didn’t crystallize overnight. It has taken discussion for members to build a consensus that school climate is a union issue. And those discussions aren’t over.

“There’s a lot more work to do to help people think about this differently, how racism presents itself economically [in terms of allocation of resources],” said CTU’s chief of staff, former social studies teacher Jennifer Johnson. “Our students don’t need punitive systems, but support systems.”

In Chicago and L.A. last year, district negotiators spent months dismissing demands that went beyond legally sanctioned topics like wages and benefits.

“Of course the district said no at first,” Inouye said. “They weren’t going to hear any ‘common good’ demands.” It took strikes to make the districts move.

CTU did not win its demand to swap out school police for support staff. But it did win increased staffing for nurses, social workers, and therapists, and new contract language about restorative justice, an alternative approach to student discipline that emphasizes solving problems and making amends rather than punishing infractions.

NEXT, PEPPER SPRAY

In L.A., the Students Deserve coalition has now set its sights on ending the use of pepper spray against students. In one incident at Dorsey High, school police used pepper spray on students who were fighting—but also ended up spraying other students who were trying to break up the fight or just walking by.

Since the random searches are coming to an end, Students Deserve presented the school board with its list of proposed school-safety alternatives. The students recommended adding more staff to offer help and guidance. They also recommended that the district involve the community, rather than the police, in a “safe passage” program to provide adult supervision on routes where kids and teens walk home from school.

Student activists will organize this campaign the same way they organized the last one, Doss said: “talking to students, doing direct action, doing things bigger.”

For the union, taking on the issue of random searches has uncovered new leaders like Hapuarachy. She said campaigns like this one have gotten her more active in the union. For her, UTLA’s mission includes “fighting for racial justice in schools, making sure there aren’t pockets of schools where students are being treated differently in other parts of the city.”