After giving something up in a previous contract, is it possible to win it back? It took a massive effort, but hospital workers in Buffalo proved it can be done.

Catholic Health is one of the two local hospital chains that dominate western New York. Communications Workers (CWA) Locals 1133 and 1168 represent 6,900 of its employees in six bargaining units.

Four years ago, Catholic Health cried poverty at the bargaining table. Threatened with layoffs, our unions reluctantly agreed to eliminate daily overtime (after eight or 12 hours, depending on the job—of particular importance to part-timers), cost-of-living increases, bonus pay for nurses who came in on short notice, and seniority-based wage scales.

After all these losses, many workers jumped ship for the union hospitals of competitor Kaleida, which offered better conditions and paid $6 to $8 more per hour. Instead of hiring to replace them, Catholic Health filled the gaps with temporary, non-union nurses—who are unfamiliar with local policies and require a lot of help.

“The staffing levels are atrocious,” said St. Joe’s nurse Heather Lawrence, a Local 1168 steward. “We’d call for more staff and tell the administration we needed them, and they pretty much ignored us.” Catholic Health also cut back on nursing assistants, who work closely with nurses to care for patients. On Lawrence’s floor, four nursing assistants were reduced to two.

THE LAST STRAW

By 2015, union leaders were determined to build a contract campaign that could reverse the givebacks. Four of the six contracts would be expiring within a year, covering 2,500 workers—including 2,200 at the flagship Mercy Hospital of Buffalo.

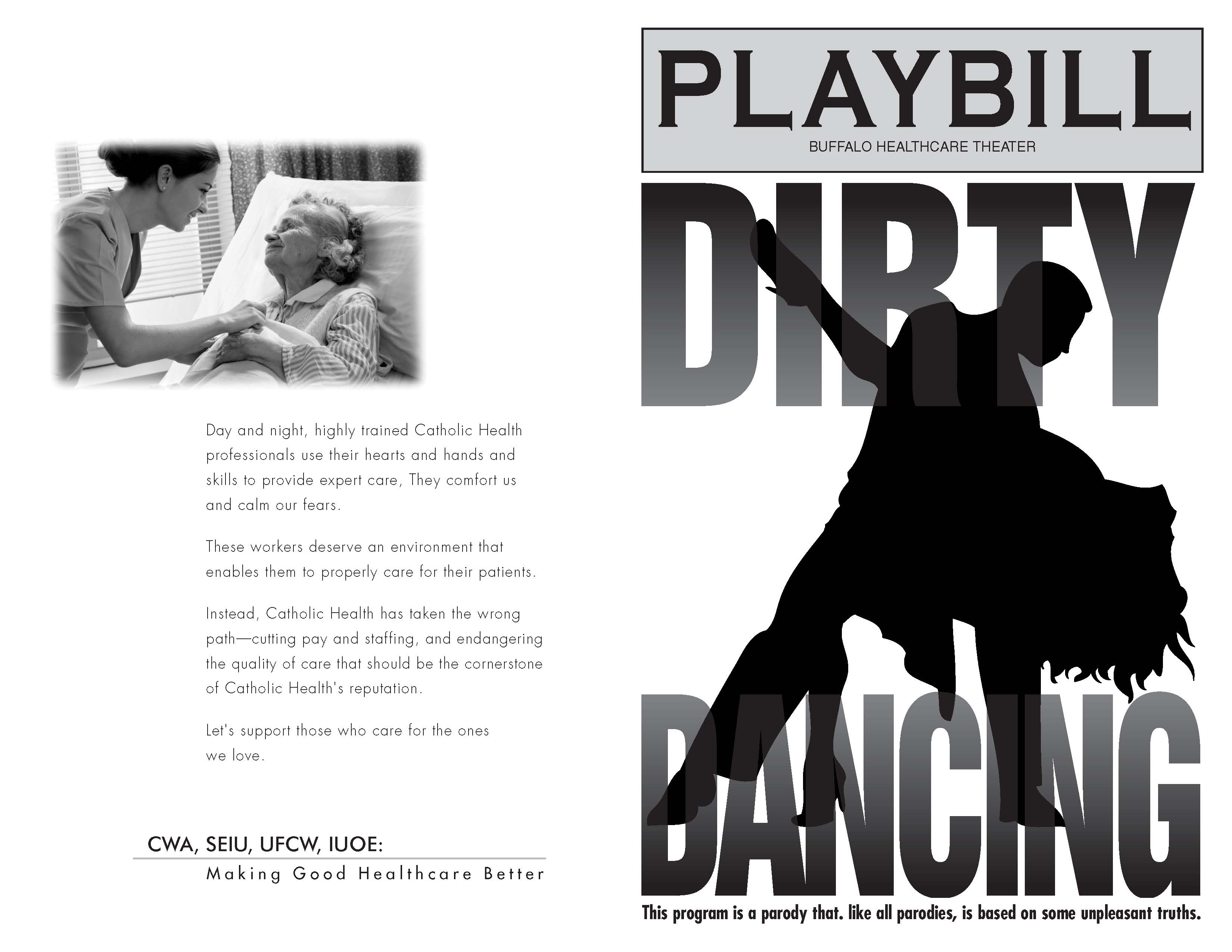

Teams of union members and staff distributed flyers at church events, art festivals, and performances, often using fake playbills (based on public source images), like this one for "Dirty Dancing," stuffed with information about our negotiations.

It helped that Local 1133 had elected a new executive board in 2014. Under the previous administration, “we weren’t even given a chance to be involved,” said Kevonna Neely, a steward and certified nursing assistant at the nursing home attached to Mercy. “I never even knew you were able to go to bargaining, or you were able to talk about real issues with your executive board.”

By now Catholic Health was doing much better, with record revenue and $340 million cash on hand—even more than the New York Presbyterian system, which is four times its size. But that didn’t stop management from demanding still more concessions, such as excluding spouses from family health plans.

Meanwhile union researchers discovered a bonus system that was rewarding upper administrators not for improving patient outcomes, but for cutting wages and benefits. Compensation for Human Resources head Michael Moley had doubled in five years, hitting $668,122—while employees were being told, “Tighten your belts.” That was the last straw.

MEMBERS WARM UP

For the first time, the unions set up a mobilizing team. Organizers set out to identify leaders in each department and shift. One on one, they asked questions like:

- Who do people go to when there’s a problem?

- Who’s the contract expert?

- Who isn’t afraid to share their opinions and ideas with co-workers?

- Who isn’t afraid to approach management with concerns?

Next the organizers met with these people, identified which were real leaders, recruited them as department mobilizers, and trained them in one-on-one conversations.

Each mobilizer took charge of communicating with 10 to 15 co-workers, distributing flyers and buttons, and setting up department meetings. Every two weeks the mobilizers met to debrief, hear the latest updates from bargaining, ask questions, and let each other know what rumors were going around.

After getting burned in 2012, many members wanted nothing to do with the union. “At first they weren’t receptive, because we had already lost so much,” Neely said. “They felt like it was going to be the same thing. But once we involved them, people saw—‘Oh no, this is nothing like last time around!’”

The mobilizers circulated a bargaining survey, asking members to identify their top concerns and evaluate the staffing and equipment in their areas. “We went to every department,” said Neely. “We started communicating with our top people who we wanted to get involved, and they helped get the surveys back.”

In another first, the union held open bargaining, welcoming any member to sit in. “They could see both sides,” Lawrence said. “They didn’t have to rely on, ‘This is what the hospital’s telling us, and this is what the union’s telling us.’”

“It opened a lot of people’s eyes to see the demeanor of our employer,” said Lisa Boettcher, another St. Joe’s nurse and the area vice president for Local 1168. “I was shocked, the ways the lawyers from Catholic Health spoke to us. They were rude, and they were not nurses. They were making decisions about running a hospital without knowing what we do.”

Members also got the chance to speak at the table, such as to describe how short-staffed their units were.

‘WE WERE EVERYWHERE’

To win, union leaders knew they would need public pressure. They had gotten a taste of the hospital system’s vulnerability during service workers’ 2014 fight for a new contract at St. Joe’s, when neighborhood door-knocking helped stave off concessions.

Though Catholic Health hospitals have grown into massive operations that take in hundreds of millions of dollars annually, local people still think of them as small community hospitals. Their children are born there; they go there for any major procedure. Many employees also live nearby.

The issue of short staffing resonated with the community, Neely said. “They knew it could have been them, or one of their family members or loved ones, in the hospital being taken care of without enough staff. For some patients, just talking to them helps—but when you’re short-staffed, you can’t do that. You get in, you do what you’ve got to do, and you go.”

To educate local residents, small teams of union members and staff distributed flyers all over the area—at church events, art festivals, and concerts by the Buffalo Philharmonic and Bruce Springsteen. Often at performances we handed out fake playbills stuffed with information about our negotiations.

Particular targets were events sponsored by Catholic Health, such as a series of talks on women in leadership, held at an art gallery. The gallery directors came out to ask leafleters, “Why are you guys out here?” We hoped that institutions like this gallery would contact Catholic Health to say, “They’re out here again! What are you guys doing to settle this?”

Members met with elected officials too. In one bargaining session, the three top lawmakers in South Buffalo (a state assembly member, a state senator, and a county legislator) spoke on our side. And our local Jobs with Justice affiliate convened a Workers’ Rights Board of experts from finance, labor relations, and the religious community. Workers testified about how Catholic Health had changed for the worse, and the board issued two scathing reports on the harms done to employees and patients.

The unions' strongest weapon was member-to-member mobilizing. But their 15-foot inflatable "Fat Cat" also gave management fits. Photo: CWA Local 1168.

Members also helped distribute 1,800 lawn signs with the slogan “We ♥ Mercy Hospital Workers.” We made sure Catholic Health felt like we were everywhere.

OUR SECRET WEAPON

In July, members at Mercy voted by 96 percent to authorize a strike. In the weeks after the vote, we organized rallies outside the hospitals. The largest drew more than 1,000 people, lining both sides of the busiest street in South Buffalo during rush hour. One of our signs read, “Just Practicing!”

And we unveiled a new secret weapon that helped push us over the top—an inflatable “Fat Cat,” 15 feet tall, wearing a large ring, pleated suit, and suspenders. It held a cigar in one hand and strangled a nurse with the other.

We debuted the Fat Cat during rush hour on the front lawn of Catholic Health headquarters, where thousands of commuters saw it. It made the rounds to each hospital and to summer festivals where community members got to see it up close and chat with workers.

As our Labor Day strike deadline drew near—with members mobilized like never before, and community pressure growing—Catholic Health finally presented an agreement on all four contracts that we could accept.

The new contracts revive wage scales that reward years of service. Over four years, pay increases of 11.75 to 17.75 percent will bring Catholic Health workers closer to their Kaleida counterparts. We kept spouses on our health plans. All these gains will help recruit and retain staff.

On staffing, we won more input on the joint labor-management staffing committee, and a commitment to add 65 new fulltime positions—on top of hiring another 70 nursing assistants and 100 nurses to fill the current staffing shortage. Most importantly, we lined up all our Catholic Health contracts so that they will expire on a common date—June 20, 2020—giving us more power in the next round of negotiations.

Ann Converso is a registered nurse, CWA organizer, and past president of United American Nurses. Patrick Weisansal is a radiologic technologist for Kaleida Health and the director of mobilizing and organizing for CWA Local 1168. Dan DiMaggio helped with reporting.