Farmworkers Taste the Fruits of Victory

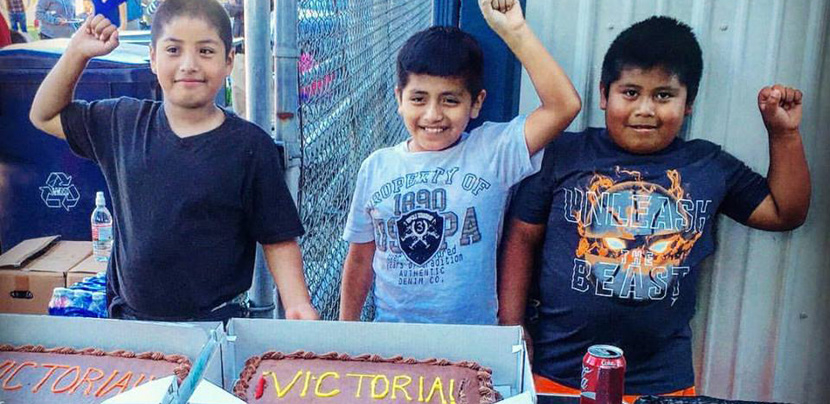

After waging countless work stoppages and an international boycott, 500 farmworkers at Sakuma Brothers Farms in Washington state have finally won union recognition. Photo: Edgar Franks

After three years of tireless organizing, 500 farmworkers at Sakuma Brothers Farms in Washington state have finally won union recognition.

The berry pickers, mainly indigenous migrants from Mexico, began their fight with a work stoppage in 2013 and never let up.

They formed an independent union, Familias Unidas por la Justicia, and launched boycotts against Sakuma and its major client, multinational berry distributor Driscoll’s, calling for the farm to recognize the union and negotiate.

This year the boycott went international, as the Washington workers joined in solidarity with berry pickers in San Quintín, Mexico, who have led massive strikes for higher wages and benefits and against sexual harassment on the job.

Pickets popped up outside grocery stores across the country. At least two food co-ops took Driscoll’s off their shelves. This growing pressure, along with ongoing direct action in the fields—workers organized four strikes this year alone—brought Sakuma to the table.

Farmworkers are excluded from the labor law that guarantees organizing rights to most private sector workers in the U.S. They can’t follow the usual route to unionize by filing with the National Labor Relations Board for an election. But that doesn’t mean farmworkers can’t build pressure on their employer to recognize a union.

Sakuma agreed to an election and on September 12, workers voted yes by an overwhelming 77 percent. It’s a rare win for an independent local farmworker union.

TURNING OUT THE VOTE

Work at Sakuma is seasonal. This year the season to pick strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries runs from June through October. (The season is shifting with climate change, says Ramon Torres, president of the union.)

In the off season, workers travel back to California to work on other crops. Most come back each year—but the low wages, uncertain hours, and difficult conditions keep turnover high, said Vice President Felimon Pineda.

This year, out of a workforce of 500, there were around 100 new workers, and the union had to reach them all. Workers mainly live in bunkhouses provided by the company.

“We organized 15 workers who could help do house meetings,” Torres said. “We went worker by worker, family by family, until people knew the truth about what we were fighting for.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Another group of 30, mostly union activists who’d been involved from the start, took charge of outreach in the town. “We did lots of training on how to organize, how to talk to other workers,” Torres said.

Because many workers speak Triqui or Mixteco, indigenous languages spoken in southern Mexico, the outreach teams divided up by language. Torres estimates the activists won over 70 percent of the newer workers.

FIRST CONTRACT

Workers gathered on September 12 to wait for the votes to be counted. Torres announced the results as workers cheered.

The next step is to bargain a first contract. Eight berry pickers make up the bargaining team.

“The first thing we want is a fair wage, a wage that our people can sustain themselves on,” said Torres. Under a complex system of piece rates, wages can range from $9.47 to $17 per hour, depending on weather, crop, and worker experience. Health benefits are another important demand.

“These are the most basic things we can fight for, but in the future, we’ll look at how to negotiate pensions, holidays, and overtime,” Torres said.

“We always have it in our minds that we are in a continuous fight,” said Pineda.

BOYCOTT STILL ON

When Sakuma agreed to an election, Familias Unidas officially called off its boycott of Sakuma clients. But the farmworkers in San Quintín are still asking consumers to boycott Driscoll’s berries.

Torres and Pineda expressed their gratitude to supporters who took up the boycott campaign across the country. The outside support helped sustain the campaign—as farmworkers went on taking risks in the fields.

“Workers lost their fear,” Pineda said. “They stopped being on their knees in front of the company, in front of the supervisors.”

“I’m really proud that our people now have the capacity to have benefits, to have another kind of life, not the life that I had,” said Torres. “Everyone is feeling really happy, but the biggest feeling is that, going forward, there is going to be a better future for their kids.”