Striking Over Grievances When the Contract's Up

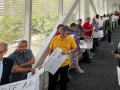

Unions that keep working after a contract expires can strike over grievances, as several CWA locals at AT&T did earlier this year. Photo: Prem Techs United.

When a contract expires, the no-strike and binding arbitration clauses are no longer in effect. That means unions that keep working without a contract can strike over grievances that happen after contract expiration, as several Communications Workers locals at AT&T have done this year.

CWA Local 4322 members in Dayton, Ohio, struck May 6 and 7 after a member was sent home for losing a $6 tool. “The company was obviously using this as a harassment technique,” said Chief Steward Jeff Mitchell, “because that kind of discipline for losing a tool had never been heard of before.”

“We thought that with the way that the contract seemed to be stalled, the membership was getting a little restless,” Mitchell said. “We wanted to show the company that we were serious about this grievance.”

One key was making sure they had a solid communication network ahead of time. Mitchell said activists had spent a month setting up a call tree as part of the mobilization around contract bargaining with AT&T (the contract expired April 11). They made sure to keep it updated as numbers changed or new people came on the job.

Mitchell said members used phone calls, rather than texts, to make sure everyone joined the strike: “I asked the mobilizers to call, and to keep calling that person until they get hold of them—I didn’t want a text to get twisted, or somebody to not get the text.”

Local leaders said the strike had 100 percent participation from 425 technicians, engineers, and service reps on the first day, though they sent the service reps back to work on day two as a good-faith gesture to the company.

Unfair Labor Practice Strikes at AT&T

Two CWA locals at AT&T Southeast have gone on unfair labor practice strikes since their contract expired August 8.

ULP strikes are more legally protected than grievance strikes, because the company cannot hire permanent replacements. Unions can convert grievance strikes into ULP strikes if, for example, the employer refuses to meet to discuss a grievance.

In New Orleans, members of Local 3410—primarily outside technicians—went on a two-day strike August 28. During earlier informational picketing, a supervisor had hit the local’s secretary-treasurer with his rearview mirror, knocking him to the ground. The union filed charges with the Labor Board for intimidation, while demanding that the supervisor be fired or resign.

“There was little to no work done on those two days,” according to President Steve Edler. He said fewer than 1 percent of the 450 members at AT&T crossed the picket line.

As of today, the supervisor has been replaced, but remains with the company on special assignment.

Edler emphasizes making sure your ULP charge is valid, as well as ensuring high participation. “If half the people cross the picket line,” he warned, “what does that say?”

In Pensacola, Florida, Local 3109 members pulled a ULP strike August 28 after a manager discriminated against a union member, threatening more severe discipline if he filed a grievance over a performance warning.

President Dan Frazier said, “You had service reps who jumped right off the phone—who told customers they had to hang up, that there was a labor dispute—folks who were doing installs, who were doing repairs, all those folks came back to the garage and turned their trucks in.” According to Frazier, “the company had no idea we were going out—as a matter of fact the local didn’t even know.”

The grievance was resolved by the end of the second day, including an agreement for no discipline.

According to Vice President Dave Murray, “the best part of it was that it opened up the eyes of the management team in this area—it was amazing the level of participation we got after that. [They said,] ‘Damn, these folks are unified, our tactics to try to split them up haven’t paid off.’”

The Dayton strike was covered by the Dayton Daily News and the local CBS affiliate.

Local 4900 in Indianapolis also organized a grievance strike at AT&T in May, after a member was suspended for three days over weakly documented “poor work.” The strike spread statewide, with 1,500 members participating.

Local officers did not call the strike, according to President Tim Strong. Instead, before the contract expired, officers “made sure our members were very educated on their rights—that they had the right to initiate a grievance strike.”

Nine hundred CWA members in Indiana had participated in a grievance strike during the 2012 negotiations.

RISKY STRATEGY

There are, however, serious risks in conducting multiple grievance strikes. The National Labor Relations Board and Supreme Court have generally held that up to two grievance strikes after contract expiration constitute protected activity, meaning grievance strikers cannot be fired.

The event that led to the grievance must have occurred after the contract expired. Binding arbitration remains in effect for earlier grievances.

However, a union can strike only once over each grievance. And if the union holds more than two grievance strikes, it runs the risk of being accused of an “intermittent strike” strategy, which is not protected by the law. NLRB rulings have decreed that unions are not permitted to strike on and off at will—presumably because the tactic would be too effective.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“Once you start doing three or four then you’re in dangerous territory,” says labor lawyer Robert Schwartz. “The employer’s going to go to the NLRB and say, ‘This is just an attempt to beat us down so they can get a contract. We have a lot of evidence that this is a coordinated campaign.’”

Grievance strikes should not be aimed at influencing bargaining—they should be called around immediate grievances or safety issues, or else they run the risk of losing their protected status. “Sometimes,” Schwartz warns, “unions make mistakes on leaflets or in newspaper articles, or the employer has spies at meetings.”

To avoid this danger, the union should refrain from linking the strike to bargaining in any way, and make clear that the strike is over a particular grievance.

Richard de Vries, a union representative for Teamsters Local 705 in Chicago, suggests a petition asking the employer to resolve the grievance. “But if it’s only 10 people who signed that petition,” he warns, “you’re going to have a hard time telling the Labor Board you went on strike because of that grievance.”

Even organizing one grievance strike can be risky. As Schwartz notes, “the grievance strike is an economic strike and it doesn’t have the super-protection of an unfair labor practice strike.” In an economic strike, the employer can hire permanent replacements.

To reduce the risk of replacements, grievance strikes should be short—generally one to two days. The union should also announce shortly after the strike begins when members will return to work unconditionally, even if the grievance isn’t resolved. Strikers are generally protected against permanent replacement once they have submitted an unconditional offer to return to work.

Unions must also be prepared for the risk of an employer lockout in response to a grievance strike.

ELEMENT OF SURPRISE

The union should try to catch the company off guard, so that managers are not prepared to hire replacements and so the strike has the biggest economic impact.

CWA members at AT&T in Minneapolis were able to surprise the company with a half-day grievance strike, a week after the ones in Indianapolis and Dayton. While they had initially planned to strike on Friday, they went out early, at 1 p.m. on a Tuesday.

Their grievance was over AT&T’s refusal to allow certain workers to use sick time to care for family members, which the union said violated Minnesota state law. Of 280 workers in the building, 220 participated. Although their grievance remains unresolved, according to Chief Steward Kieran Knutson, “several managers said grudgingly that they’d never seen a union so strong, and gave us some respect that we were actually able to pull the trigger.”

Knutson said the strike forced AT&T to transfer calls to other call centers, “where they don’t have workers necessarily trained to take the calls or assist on whatever issue it is.”

He said the element of surprise is especially key in telecom: “With the telecom technology, if they have notice and time to plan, they really can outmaneuver us. It does take us being creative and trying to shut down bigger chunks of it, too, so it’s not just one little piece that can be routed around.”

Though it might make surprising the company more difficult, de Vries suggests that unions exhaust the grievance procedure before launching a grievance strike. “You want the strike to be combined with a certain degree of righteous indignation” on the part of members, he said, so you don’t want members questioning why management wasn’t given a chance to settle.

From a legal point of view, a union can pull a grievance strike after contract expiration even if the grievance has not gone through all the steps of the procedure. But the union should make clear to the employer what the strike is about and how the issue can be resolved.

TEST OF STRENGTH

De Vries argues, “The principal reason for [a grievance strike] is to test out the members’ strike-readiness. Can you organize successfully to have a 95 percent turnout for a one-hour strike activity?”

“This is truly a solidarity-building tool,” says de Vries, “but it doesn’t happen without taking all the other baby steps that lead up to it. Have you had a t-shirt day? Have you had a one-hour practice picket? Unless all of those other kinds of activities are also going on, it’s hard to have a successful grievance strike.”

Knutson agrees: “Don’t just assume you can call a strike—it has to be built for. The membership has to be part of the strategizing, part of the decision-making, and that means building an organization ahead of time, with stewards’ committees, mobilizing committees.” He suggests a survey to assess workers’ willingness to participate.

While grievance strikes cannot be aimed at bargaining, Frazier of Local 4322 said he thinks his local’s strike did “cause the company to come to some resolution on bargaining.” He was at the bargaining table when he got word of the strike. “The company’d get a phone call, we’d get a phone call, so it made it difficult to have good dialogue… They wanted to resolve the issue so we could go on.”

A well-organized grievance strike can show the company the union’s strength, and give members a taste of their own power. “Now the company knows we have the ability to pull people out,” says Knutson, “and people know that we can do it. So the next time there’s a contract, or there’s a serious issue, people will know that’s a tactic that’s available to us.”

For Strong, the grievance strike “is a very, very important tool in today’s environment—a full strike is very difficult.” In his experience, “the members seem to really enjoy the event—the participation rate has been 99 percent. It’s a low economic impact for the member and high chaos for the employer.”

Knutson says his local made sure to preserve the memory of their strike, as preparation for the future. “We made commemorative posters,” he said, “and handed out pizzas and posters a week later—and the posters are still up in many people’s cubicles.”