First Contracts: How to Avoid Delay, Disappointment and Decertification

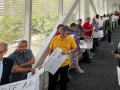

After Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital workers voted for a union, the boss managed to hold up certification for a year. After that, they didn't jump straight into negotiations, instead building up trust and even putting union opponents on the bargaining team. Photo: NUHW.

This time it wasn’t even close. After three years of struggle, exhausted and discouraged, workers at St. Charles Medical Center in central Oregon voted 334 to 212 November 1 to give up on being a union. In 40-some bargaining sessions, they never reached a first contract.

“We may have underestimated our administration,” said Joanne Kennedy, a pharmacy tech and bargaining team member. “For a short while they may have entertained an idea of us having a union. But then they decided there was not to be one. Ever. Period.”

Kennedy has worked at the hospital more than three decades. She is a veteran of three unsuccessful union drives, most recently a campaign with Service Employees Local 49, where I worked with her for two years as an organizer.

No one I met failed to adore Joanne Kennedy, except maybe the hospital execs. She held her department together through the tensest times by sheer force of personality. When she and her co-workers won a close election in January 2011, it marked the largest private-sector organizing victory Oregon had seen in decades.

Kennedy has reached an age when most people think about retirement. “I am looking at other options for my own survival now,” she wrote me after the defeat, since she can’t count on a pay raise.

“I still feel like something hanging in hunting camp.”

WORN DOWN

The day a new union is certified, the clock starts ticking. After one year, if there’s no contract, the company gets its next chance to bust the union: a minority of workers can file a petition to decertify, and the Labor Board will schedule another vote. If this is the boss’s game plan—as it was at St. Charles—bargaining is an exercise in delay.

“The companies are brilliant at negotiating without really negotiating,” says veteran organizer Gene Bruskin.

What makes getting a first contract so tough? As anyone who’s been through it knows, the boss’s tactics can work—people get scared and change their minds—so you have to keep asking supporters to confirm, reconfirm, and re-reconfirm where they stand.

People who don’t like conflict—which is most people—may start avoiding you. Turning out support, first for the vote and then for a contract campaign, requires calling a co-worker at home if you can’t track her down at work, and showing up on her doorstep if you can’t get her on the phone.

Cornell labor scholar Kate Bronfenbrenner’s research shows that multi-year contract delays are far from exceptional. When workers win a union vote, she found, half the time they don’t have a contract a year later. A third of the time, there’s still no contract after two years.

Labor law reform was supposed to fix this. The Employee Free Choice Act proposed that, if three months of bargaining didn’t produce a first contract, either party could bring in a federal mediator—and if a month of mediation didn’t work, binding arbitration would follow.

But EFCA isn’t in the cards anytime soon, since President Obama, who promised it in his 2008 campaign, abandoned it after being elected.

Legal scholar Ellen Dannin argues the laws already on the books are better than we think.

The trouble, she says, is in how judges have weakened them over the years with unfavorable interpretations—like weak penalties for employers who fire union activists, and allowing employers to implement their final offers when bargaining reaches impasse.

Rather than trying to amend the law, Dannin says, labor should file strategic suits to force the courts to reexamine these interpretations.

When you do finally talk to her, she may blame the union for the tension and fear she is feeling. Multiply this by months and months.

Workers I met who changed their minds about the union at St. Charles didn’t stop caring about patient safety, outsourcing, or fair pay. They just gave up hoping this wearying struggle would ever bear fruit.

But it’s not impossible. Plenty of workers win strong first contracts. I asked workers and organizers from four campaigns—three victorious, one still fighting it out—for their top strategic tips.

WEAR SUPPORT ON SLEEVE

A successful contract campaign starts early—long before the union is voted in, some organizers told me. The sooner you can get people to overcome their fears, the better.

Cablevision workers in Brooklyn established from the beginning a culture of accountability that has served them well.

Workers began the drive on their own steam, then walked into the Communications Workers office carrying 100 signed authorization cards—an unusually promising start.

But organizers, who knew what kind of bruising fight the workers were in for, felt the old-fashioned card the workers had used was too minimal, its language just the basic formula that triggers a yes-no vote on the union.

So the workers started over with a new card, this one asking for a deeper commitment.

“I will not sit back while my co-workers on the Organizing Committee stand up for a union on my behalf,” the card read. “They have my back—I have their back.” Workers were invited to check a box agreeing to make their names public as soon as the union reached majority support.

In the lead-up to their election, as they endured the tactics of a union-busting firm, workers wore red “CWA Solidarity” wristbands and stood up to management in captive-audience meetings.

Committee members told co-workers, “‘If you’re not going to wear this band, I don’t even want you to sign a card,’” said Tim Dubnau, organizing director for CWA District 1. “‘What you’re really saying is you want me to fight your battles for you.’

“If someone took their wristband off, the committee would go to them and say, ‘Why is your band off? Put it back on. That’s not right.’”

Since workers won that vote, “Cablevision is doing everything they can to delay,” audit technician Jerome Thompson told me.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The company even tried firing Thompson, a main leader of the drive. But his co-workers sprang into action: 200 wore a sticker that read simply “Jerome,” and 40 stewards jammed into the vice president’s office, demanding Thompson’s job back.

“The very next day, the boss rehired Jerome with back pay and said it was a misunderstanding,” Dubnau said. “We didn’t file an unfair labor practice. It was shop-floor militancy.”

At the one-year mark, workers showed off their union spirit with a chilly Martin Luther King Day action outside one of the company's garages. A recent petition demonstrated more workers support the union now than voted for it last January.

“Once they realize there’s no way the union is going to leave," said five-year employee Eric Ocasio, "they’ll have to settle down and agree to a contract with us.”

SWEAT THE SMALL STUFF

Organizers also reminded me you don’t have to wait till a contract is in place to start acting like a union—and getting some victories under your belt can only help.

After workers at an IKEA furniture factory in Danville, Virginia, organized with the Machinists (IAM), they wasted no time, quickly training up a corps of stewards and asserting their rights. Soon nervous supervisors would fetch a steward before daring to discipline a worker.

“It was just fun,” said Bill Street, director of the IAM’s woodworkers department. “My perfect job is, you send me in the day they’re certified and we get to play until they bargain the first contract.”

Street sees this period as the height of a union’s power, because you have the legal right to insist management bargain over every change in working conditions (see this Steward's Corner on working without a contract). The union will likely sign some of this power away in the eventual contract, with a “management’s rights” clause that covers matters like scheduling shifts, hiring, and assigning work—and generally a “no-strike/no-slowdown” clause too.

But before the contract, it’s all up for grabs—so the more you make every rule change into a battle, the more incentive you create for the boss to stop stalling and get a deal.

At the Danville factory, the union spent hours negotiating over items the plant manager was used to deciding unilaterally. It drove him crazy, Street said.

As important, fighting out issues on the shop floor will build workers’ confidence in their new union.

Street described how stewards led an impromptu strike over safety. Two workers had sliced their hands on the machinery one day, because everyone was working an unfamiliar line, without training.

After the second accident, two stewards confronted the supervisor, demanding that workers be sent back to their usual positions.

“The stewards shouted down the line, ‘Everybody step away from your machines.’ Everybody took a step back,” Street said.

The supervisor gave in.

PREEMPT THE BOSS FIGHT

Of course, at the same time you are preparing workers to survive a protracted fight, you’d like to discourage management from starting down that road.

Gene Bruskin, former strategic campaigns director for the Teachers union (AFT), described how careful preparation helped preempt a decert at a Chicago charter school chain. During the organizing drive, the union identified and quietly approached influential community leaders with connections to the CEO and board members.

The same day the educators went public, marching on their principals to demand a union, the CEO and board started getting phone calls from these leaders, offering advice: Be reasonable. Don’t go to war with Chicago labor. You can talk to these people.

“We assumed the worst,” Bruskin said. “We tried to be ready in every way.”

It worked. The CEO hesitated a few days while the calls and other public support continued to escalate, then dismissed the anti-union attorney he had hired. It was a decisive moment, Bruskin said, in a campaign that would produce a good first contract.

HEAL DIVISIONS

Organizers say the time right after the election can be pivotal—a crucial window to reach out to “no” voters before their positions harden.

The boss at Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital in California managed to hold up certification for an entire year after the vote, while a divided workforce waited in limbo. The slim margin of victory and momentum-killing delay were almost “a recipe for running a decert,” said organizer Peter Tappeiner.

So when the board finally made it official, the National Union of Healthcare Workers (NUHW) didn’t jump straight into negotiations.

Instead, said Tappeiner, the union held meetings open to all—including people who hadn’t supported the union. “We didn’t allow the polarization that happens in an election to just stay,” he said. “We gave ourselves the time for people to get to know each other and build a relationship of trust.”

A small but outspoken group opposed union shop, the requirement that everyone join the union. On my ill-fated campaign at St. Charles, a couple of workers hostile to the union effort even tried to run for the bargaining team just to flog this issue. But they balked when we told them they would have to sign membership cards to show their good-faith commitment to the negotiations.

At Santa Rosa, where organizers judged a membership drive would have been divisive, they took an opposite approach.

In fact, some still-wary workers were elected to the 25-member bargaining team, which chose most proposals by consensus. Any employee could attend negotiations and ask questions. The transparent process showed workers the horror stories they’d heard about unions weren’t true—and management’s behavior at the table was an eye-opener too.

“Many times the people who were the strongest advocates against the union can become your strongest union supporters,” said John Borsos of NUHW.