A Second Disaster Coming to the Gulf? Hazards Abound for Cleanup Workers

Jason Anderson, one of 11 workers killed during April’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, had warned his family that BP was pushing speed-up and straying from safety protocols.

Without a union to take his concerns to, Jason turned to his wife, Shelly. “Everything seemed to be pressing to Jason, about getting things in order, in case something happened,” Shelly confessed during an NBC interview.

Today, 27,000 workers in the BP-run Gulf cleanup effort may still be in danger. Some are falling sick, and the long-term effects of chemical exposure for workers and residents are yet unknown.

Workers lack power on the job to demand better safety enforcement. They fear company retaliation if they speak out and are wary of government regulators who have kept BP in the driver’s seat.

BP carries a history of putting profit before worker safety. A 2005 refinery explosion in Texas City, Texas, killed 15 and injured another 108 workers. The Chemical Safety Board investigation resulted in a 341-page report stating that BP knew of “significant safety problems at the Texas City refinery and at 34 other BP business units around the world” months before the explosion.

One internal BP memo made a cost-benefit analysis of types of housing construction on site in terms of the children’s story “The Three Little Pigs.” “Brick” houses—blast-resistant ones—might save a few “piggies,” but was it worth the initial investment?

BP decided not, costing several workers’ lives. Federal officials found more than 700 safety violations at Texas City and fined BP more than $87 million in 2009, but the corporation has refused to pay.

BP NO EXCEPTION

According to the Steelworkers union, the oil industry saw 13 fires that caused 19 deaths and 25 injuries during April and May alone, including Deepwater Horizon. Oil refineries across the U.S. averaged a fire each week.

Jim Savage, local president at a south Philadelphia refinery, sits on the USW’s national refinery bargaining council. Savage said BP is no exception. Safety violations are rampant in the industry, especially in the hectic final 12 hours before production starts up—the same period when the Deepwater disaster took place.

The Steelworkers requested in early July that the oil giants reopen bargaining over health and safety, after they turned aside the union’s proposals in negotiations last year. The oil firms have refused.

CLEANUP RISKS

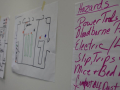

Now workers in the cleanup effort face similar challenges to those Jason Anderson and his 10 slain co-workers woke up to each morning. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) policy analyst Hugh Kaufman says workers are being exposed to a “toxic soup,” and face dangers like those in the Exxon Valdez, Love Canal, and 9/11 cleanups.

The 1989 Exxon Valdez experience should have taught us about the health fallouts of working with oil and chemical cleaners, but tests to determine long-term effects on those workers were never done, by either the company or OSHA. It appears they have faced health problems far beyond any warnings given by company or government officials while the work was going on.

Veterans of that cleanup, such as supervisor Merle Savage, reported coming down with the same flu-like symptoms during their work that Gulf cleanup workers are now experiencing. Savage, along with an estimated 3,000 cleanup workers, has lived 20 years with chronic respiratory illness and neurological damage.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

A 2002 study from a Spanish oil spill showed that cleanup workers and community members have increased risk of cancer and that workers with long-term exposure to crude oil can face permanent DNA damage.

So far, Louisiana has records of 128 cleanup workers becoming sick with flu-like symptoms, including dizziness, nausea, and headaches, after exposure to chemicals on the job. BP recorded 21 short hospitalizations. When seven workers from different boats were hospitalized with chemical exposure symptoms, BP executives dismissed the illnesses as food poisoning.

BP bosses have told workers to report to BP clinics only and not to visit public hospitals, where their numbers can be recorded by the state.

Surgeon General Regina Benjamin has said that without the benefit of studies, or even knowing the chemical makeup of the Corexit 9500 dispersant (which its manufacturer calls a “trade secret”), scientific opinion is divided on long-term health impacts to the region.

Workers in the Gulf are not receiving proper training or equipment, says Mark Catlin, an occupational hygienist who was sent to the Exxon Valdez site by the Laborers union.

EQUIPMENT LACKING

BP has said it will provide workers with respirators and proper training if necessary, but the company has yet to deem the situation a health risk for workers. The Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) provided respirators to some workers directly, but BP forbade them to use them.

One rationale behind banning respirators is that they could increase the likelihood of heat-related illnesses, but Kindra Arnsen, an outspoken wife of a sick fisherman turned cleanup worker, points out that many workers are fishermen accustomed to the Gulf heat who can work safely given enough hydration and time for breaks.

Workers who question the safety of their assignments, choose to wear their own safety equipment, or speak out about the risks are threatened with losing their jobs, according to Arnsen and LEAN’s executive director Marylee Orr.

Arnsen has also spoken out in fear for her community of Venice, Louisiana. She describes illnesses and rashes her young children and husband have suffered since the explosion and cleanup and says there are days when officials tell residents to stay indoors.

PR POWER

The Center for Research on Globalization has speculated that banning respirators and other protective gear for workers is part of BP’s public relations campaign to control how bad the disaster looks. This follows a pattern of threatening reporters who get too close to the hardest-hit areas, blocking media access to workers, exaggerating claims of mitigation of the spill’s impact, and using dispersants that make much of the oil invisible.

Both the EPA and OSHA have criticized BP’s safety plan, which allows workers without respirators to stay in an area when air pollutants are high, doesn’t evacuate workers when conditions become unsafe, and contains no upper limits of exposure to carcinogenic gases found in crude oil.

Catlin, the occupational hygienist, says the protocol seems to be written in a way that allows BP to continue operating under conditions that, in other settings, would halt work.

Fishery industry organizations have joined with environmental groups to demand respirators and other safety equipment and training for workers. The coalition has launched bpmakesmesick.com, aimed at pressuring the Obama administration to better enforce health codes during the cleanup.