Interview: Can a Labor-Backed Candidate in Nebraska Inspire More Working-Class Independents?

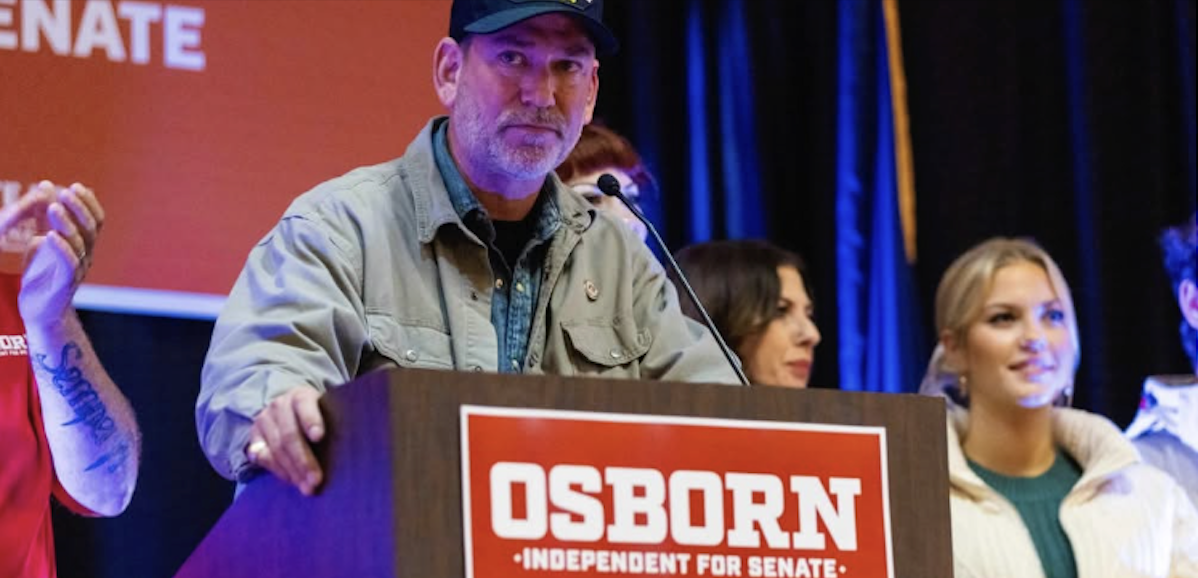

Dan Osborn’s independent U.S. Senate run in Nebraska came closer to winning than anyone expected.

While running for U.S. Senate in Nebraska, working class candidate Dan Osborn characterized the Senate as “a country club of millionaires that work for billionaires.”

In November, he almost crashed their party.

Osborn, a 49-year old former local union president who helped lead a multi-state strike against Kellogg’s cereal company, was recruited by railroad workers to challenge two-term incumbent Senator Deb Fischer, a Republican. Rail is a major industry in Nebraska, and Fischer had voted to break the 2022 national railroad strike. She also opposed the Railway Safety Act.

Osborn’s labor-backed independent campaign was, for many months, ignored by the mainstream press and even progressive media outlets (though we covered it).

The Nebraska Democratic Party, which ended up not fielding a candidate, was miffed by Osborn’s decision not to participate in its primary or seek the party’s endorsement. Still, by October, the Senate Majority PAC had shifted $3.8 million to an independent expenditure committee supporting him.

Osborn’s candidacy was initially given little chance of success by national and local experts because he was, in their view, a complete unknown. Union political directors in Washington, D.C., were skeptical as well.

But Osborn’s campaign clearly hit a chord among working people. Last fall, the New York Times reported, Republican Super PACs and national party operatives were forced to launch a $15 million advertising blitz to blunt Osborn’s homestretch momentum against Fischer. On election day, Osborn’s 47 percent showing against Fischer—in a state Kamala Harris lost by 59 to 39 percent—confirmed the crossover appeal of Osborn’s blue-collar agenda among voters in Nebraska.

This unexpectedly strong showing drew post-election praise from Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and others. As Sanders told The Nation, Osborn ran as a strong trade unionist who “took on the corporate world’ in an “extraordinary campaign” that reached working class people all over Nebraska and proved that many want real change.

In late November, when Osborn was preparing to return to work as a rank-and-file member of Steamfitters Local 664, he and his supporters formed a Working Class Heroes Fund. The goal of this new political action committee, which has already raised $200,000, is to recruit, train, and support more blue-collar candidates for public office.

Osborn also hopes to persuade more working-class people to vote in their own economic self-interest, rather than for parties and politicians backed by “special interests and billionaires.”

Osborn’s call echoes that of union activists in the late 1990s, who launched a ten-year effort to build a Labor Party as a political vehicle for the working class. One of its goals—unfortunately, never achieved—was to help more working-class leaders run for office themselves, as challengers to business-backed candidates from the two major parties.

In this interview, longtime Labor Notes contributor Steve Early asked Osborn about his experience as a first-time political candidate, how he outperformed Harris against a MAGA Republican, and his hopes for the Working Class Heroes Fund.

Based on your recent campaign experience, what advice do you have for other labor activists similarly disenchanted with both major parties and thinking about running for office?

Hopefully, our campaign will pave the way for more truck drivers, nurses, teachers, plumbers, carpenters, and other working-class people to run for office, challenge the system, and win by uniting the working class across party lines.

People are hungry for anything outside the two parties. They know that you shouldn’t have to be a self-funding crypto billionaire to get elected to public office. They’re hungry for working-class candidates. It’s a huge opportunity for all of us, and we need to seize it.

Your best bet for a labor candidate is someone who needs to be actively recruited and did not look in the mirror one day and decide they should be a state legislator or member of Congress. If there hadn’t been people in the Nebraska labor movement who came to me and asked me to run, it would probably never have occurred to me.

If you’re running independent, you should be independent. Changing your party registration overnight can be a liability, and I would discourage people who are thinking of being “tactically” independent from doing this.

We will always start out under-resourced and outgunned. So we have to pick our spots. A lot has to go right. It definitely helps to end up in a one-on-one general election contest with an out-of-touch Republican incumbent, rather than a three-way race in which a labor independent might be regarded as a “spoiler.”

How were you able to convince local and national unions that your independent candidacy was viable?

Well, it took a while. We didn’t see our first union donation check until about five months after I announced. The United Association (UA) people [Plumbers and Pipefitters] believed in and fought for us from very early on. The railroaders of Central Nebraska were very strong for us. But they were exceptions. It took most labor people a long, long time to come around.

Union resources are limited, and decision makers want to see you’re for real. Those early days when you have to prove yourself, that’s what really tests you as a candidate. We had some dark days early on, believe me.

I wish there was a little more willingness on the part of the people who hold the purse strings to lift up candidates earlier in an election cycle. But eventually, unions saw us raising money. They saw the polling about Deb Fischer’s unpopularity and electoral vulnerability. And that’s what it took to convince them.

When you got more labor endorsements, how did you work with Nebraska unions to involve their rank-and-file members as signature gatherers during your nomination petition drive or as phone bank and door-to-door canvassing volunteers in the homestretch?

It’s interesting. Even at the end, we didn’t see huge organized labor turnout efforts. There were unions who did great work on the ground, for sure. The UA turned out their apprentices in bulk. Insulators Local 39 in Omaha punched way above their weight. The railroad unions were with us from the start.

But mostly—and I think this is true in other states—our unions don’t generally have some great ground game, ready to go, even on behalf of someone who is one of their own. We definitely tried to get every local to release staff for election work and set up their own canvassing operations and phone banks to involve more members.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

We had some successes. We had individuals who went hard during petitioning. People like a big event. We had big turnout for our rallies with [UAW President] Shawn Fain in Lincoln and Omaha where people went out and canvassed beforehand.

Mostly, I think the lesson is you can’t count on unions to just show up in force at your door, if they don’t normally organize themselves for elections. For that, you really have to push and, until the very end, we didn’t really get there.

Were there some labor and consumer issues that you stressed that resonated with voters better than others?

I had 180 publicly-advertised campaign events. A lot of people at them were just like me, people who live paycheck to paycheck, working for a living. Whether it was a group of five or 80, we would sit down and focus on issues.

“Right to Repair” was one issue that really resonated across the board. Cutting taxes on overtime pay was another—and we were out in front of Trump on that one. Inflation, of course. People don’t always know quite what they want done about inflation, but they want to know that you share their concern about it.

It’s a big advantage, when you’re going up against a millionaire or a billionaire, if you feel the impact of inflation personally. It gives you some credibility if you’re hit with it on every trip to the grocery store too. So I just spoke to people about this and other problems, like a normal person, not a politician. And that was the secret to my almost success.

Was your experience dealing with the press as a local union leader, during the Kellogg strike, helpful preparation for becoming a political candidate and explaining your platform to newspaper, TV, and radio reporters?

Extremely. In a lot of ways, an electoral campaign is like a long strike. The key is keeping people together and fired up, raising money, and yes, working the media. The press relationships we developed during the strike carried forward, and it was definitely helpful not to go into all those candidate interviews cold. When the lights go on, you have to sound okay.

Your campaign produced a funny video about big money in politics, that depicted your opponent as a NASCAR driver in a jacket festooned with corporate logos—Goldman Sachs, Northrup Grumman, Google. Should others try this same humorous approach to a very serious topic?

I sure hope so. We had great ads—due to us having a strong message and bringing in really good people to help make them. There are a lot of consultants making political ads that just aren’t great. We saw the results on TV about fifty times a day last October in battleground states. Don’t hire those people.

Donald Trump urged his Nebraska fans to choose Fischer over you because, in his words, you’re part of an anti-American cabal of “Marxists, Communists, and Lunatics on the Radical Left.” Did your response, in the form of a video testimonial from fellow veterans, help counter this attack?

Definitely. People like a veteran. They like the service background. Especially when you’re trying to run without a party label, it helps to have that background.

How can the Working Class Heroes Fund–with the mailing lists, donor network, and volunteers you assembled—aid other candidates in your state or elsewhere?

It’s definitely a valuable list if you’re a new candidate looking for some ready-made support. We started with nothing, and I’ll do what I can to make sure that independent working-class candidates entering races in ’26 don’t have it quite so tough.

There’s a lot we’re still figuring out. We’ll be keeping people posted about what we’re up to. And we’ll be opening the door for anyone anywhere who wants to run these kinds of campaigns.

Labor Notes readers who have thoughts and ideas should not hesitate to reach out—on your own behalf or someone else’s at: www.workingclassheroes.fund/nominations.

We’ll definitely be letting people on our campaign list know about workers on strike who need their financial support.

What are you own personal post-election plans?

I’m going back to work as a steamfitter because, after the election, I tried to call all my bill collectors, and they didn’t care that I just ran a “close Senate race.” They wanted their money—for my mortgage, car payments, insurance, and electrical bills.

But if I have to go around the country on my weekends to help other working-class people get a seat at the table—in their city council, county board, state legislature, or Congress—that’s how I want to help.

Steve Early is a NewsGuild/CWA member who was a co-founder of Labor for Bernie. His most recent book, co-authored with Suzanne Gordon and Jasper Craven, is Our Veterans: Winners, Losers, Friends and Enemies on the New Terrain of Veterans Affairs.