Southern Service Workers Launch a New Union

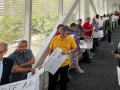

Hundreds of service workers from across the South gathered in Columbia, South Carolina, November 17-19 to launch the Union of Southern Service Workers, backed by SEIU's Fight for 15 and a Union. “This feels amazing,” said restaurant worker Jamila Allen. “Just saying I’m in an official union gives me more power. I’m going to spread it everywhere: if you’re struggling on the job and you need help, join USSW.” Photo: Raise Up

Hundreds of service workers from across the South gathered in Columbia, South Carolina, November 17-19 to launch the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW), taking their fight to a new level.

The new organization grows out of the Raise Up, the Southern branch of the Fight for $15 and a Union, a movement backed by Service Employees International Union (SEIU). In addition to fast food, members work in hotels, gas stations, retail, home care, sit-down restaurants, and more.

Some of these workers have been organizing their industries for a decade with Raise Up—fighting for higher wages and better working conditions. Others have only recently joined the effort—including many who felt that the pandemic exposed how essential their work was, and how little corporations and politicians valued them.

Labor laws are ineffective for most workers, particularly Southern workers. The National Labor Relations Act excluded agricultural, domestic, and tipped workers, who have comprised a relatively large share of the Southern workforce. Southern states are more likely to have right-to-work laws and less likely to have authorized public sector bargaining rights.

For this reason, the USSW is forming itself as a union now—not waiting to be sanctioned by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Signs posted around the meeting described a union as any group of “workers coming together to use our strength in numbers to get things done together we can’t get done on our own.”

Participants at the summit voted to form the USSW; they signed membership cards. They affirmed their plan to win by any means necessary, using four strategies: uniting across employers and sectors, direct action, community unionism, and anti-racism.

A committee of workers from different chapters was involved in setting the vision and strategy for the new union, as well as planning the summit itself. This committee will help determine the leadership structure of the new union.

UNITE ALL WORKERS

The new union brings together workers across employers and sectors. Yet they share similar conditions of work: low wages, irregular hours, unsafe working conditions, and a lack of respect from supervisors who treat them as disposable or subject them to racial and sexual harassment.

Worker after worker spoke on plenaries and in an open-mic speak-out about their experiences growing up in families of service workers—living in poverty and sometimes going hungry. Some left school early to help their families pay their bills.

They continue careers in low-wage service jobs, moving between employers and sectors but always facing similar poor pay and working conditions. Only by uniting can they make the structural changes necessary to break the cycle and change the work for all.

DIRECT ACTION

Worker-led direct action is the second key strategy. Workers have already been winning in the workplace through worker-led direct action, as part of Raise Up.

Jamila Allen works at Freddy’s Frozen Custard and Steakburgers in Durham, North Carolina. She joined Raise Up in 2018, but didn’t decide to start organizing her co-workers until the pandemic, when she found out the general manager had come to work sick with Covid and hadn’t notified the staff.

Jamila and her co-workers contacted Raise Up organizers and began a petition, calling on management to implement a Covid policy. When that didn’t work, they called a one-day strike—followed by a week-long strike that finally got the attention of corporate headquarters in Kansas.

Corporate didn’t like the bad press, so Freddy’s agreed to create a Covid policy and provide a raise. When a manager failed to implement the policy, though, Jamila and Ieisha organized a third strike, getting every co-worker on board. The strike was a success, and management began to implement the new policy in 33 Freddy’s locations.

COMMUNITY UNIONISM

Community unionism is a third prong of the new union’s approach. Civil rights leaders Rev. Nelson Johnson and Joyce Johnson of Greensboro, North Carolina, spoke about the need to unite workplace and community struggles.

“It’s a mistake to see community and labor as separate,” Rev. Johnson said, since working conditions are intricately connected to housing, education, and health. Most of the workers struggling to win better conditions on the job are also facing challenges finding affordable, secure housing. Young people have to cut back on school in order to take jobs and help their families pay the bills.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Workers belong to chapters based on region. Eshawney Gaston, a fast food worker in North Carolina, said that members of her chapter planned to talk to co-workers and neighbors—knocking on doors to let people know about the union and ask them to sign a membership card. They also planned strikes and actions to take place around their region.

The USSW also is building community within the union. Some workers are already family; multiple generations work in low-wage work. Others spoke of creating new family through organizing.

“In the beginning, I blamed white people, Latino workers—they’re probably making my wages low---and that’s these corporations winning,” said Terrence Wise, a fast food worker and Fight for $15 and a Union leader. “But then I realized Trish is my sister, Dawn is my sister…we family here. We all we got.”

ANTI-RACISM

“If you change the South you change the nation” was a common refrain throughout the summit.

The USSW is founded on an analysis that the country was built on the unpaid labor of enslaved workers and continues to exploit Black and brown workers today. The legacy of slavery and Jim Crow hurts all workers by keeping them divided.

“We have corporate bosses and racist lawmakers, and they feel the power of us organizing,” said Cummie Davis, a home care worker from Chapel Hill, North Carolina. “So they passed racist laws to keep us from forming unions.” In addition to NLRA exclusions and right-to-work laws, other restrictions like minimum wage pre-emption have a greater impact on Black and brown workers who comprise a greater share of low-wage workers.

The summit featured videos and speakers highlighting the history of resistance in the South. “We stand on the shoulders of unsung freedom fighters,” said retail worker Beth Schaffer. Creating a multi-racial union, built on an anti-racist analysis, would be key to winning, speakers told the crowd.

MAKING THEIR OWN WAY

Throughout the summit, speakers affirmed their commitment to win by any means necessary. The time is now to make bold demands, as Raise Up leader Mama Cookie told the crowd.

These demands include better wages and schedules, but also the power to make decisions about their work. Ieishsa Franceis told the crowd, “Of all our demands, the one that stands out the most to me is our demand to have decision-making power. We should be the ones deciding on what proper safety equipment, on what a fair wage is, when we are scheduled to work.”

The USSW is building a union in its own way. Brandon Beachum, from Atlanta, had been part of an effort to unionize when he worked at a grocery store—but when union organizers came in and started talking about the NLRB process, the workers were discouraged. With high staff turnover, they knew they could not maintain their organizing momentum throughout a long legal process.

In his current job at Panera Bread, he contacted Raise Up organizers who met with him and his co-workers and told them, “There’s three of you sitting at a table talking together—you are a union!” Beachum felt inspired by this activist approach to unionizing. “Instead of saying ‘the union,’ we say ‘us,’” he said. “Instead of the NLRB doing something for us, we are the ones with power.”

Workers left the summit inspired and ready for action. Gaston, who had been organizing since a McDonald’s co-worker invited her to a meeting in 2016, was moved by the experience.

“We have strength in numbers,” she said. “There’s a difference between saying it and seeing it here, with all these people coming together.”

“This feels amazing,” Allen added. “Just saying I’m in an official union gives me more power. I’m going to spread it everywhere: if you’re struggling on the job and you need help, join USSW.”

Stephanie Luce is professor at the City University of New York’s School of Labor and Urban Studies and the author of several books on living wage fights.