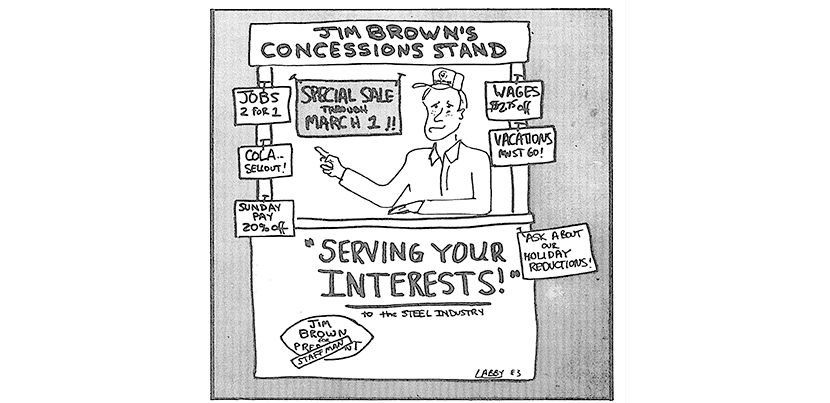

Concessions Didn't Work Then and They Won't Now

This vintage 1980s cartoon originated in Steelworkers Local 1066, where the president, Jim Brown, favored making concessions to the steel industry. It spread to other locals, where it was copied with the appropriate president's name inserted. Cartoon: David Labby.

As union members return to their jobs, employers will ask them to open their contracts and take concessions.

They probably won’t be called “concessions” this time; employers’ demands for wage cuts and work rule changes will just be “common sense.” “We’re all suffering so we should all sacrifice,” we’ll be told. To save your job, your employer needs your cooperation.

Of course, many union leaders today have never gone to the table without facing a demand for rollbacks of some sort. Since the modern era of concessions began in 1979, we’ve seen more than a generation of givebacks, punctuated with gains here and there when the economy was better.

The result is that from the recovery of 1983 till 2019, union workers’ wages, adjusted for inflation, were almost flat (which is still better than nonunion workers’). Wages increased an average of 8.4/100 of one percent per year for 36 years. If you’d made $600 in 1983, you’d have gotten, in effect, a raise of 50 cents a year.

Once again in 2020 and 2021, concessions will be sold as a way to save jobs. But even a cursory look at the record shows that concessions have not saved jobs.

THE GOOD OL’ DAYS

Here’s a look at how concessions began 40 years ago, the arguments for them then, and the record. We’ll use the auto industry, which used to set the standard for other contracts, as our main example.

In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, each union contract was better than the last (broadly speaking). Unions expected it and employers expected it.

That statement comes with a big exception: wages and benefits were improving but working conditions were not. Employers’ push for productivity heated up in the 1980s but was already underway in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers, called the auto plants “gold-plated sweatshops.”

The iconic strike of the era was at General Motors’ Lordstown, Ohio, plant in 1972, where workers were not happy with an assembly line moving at 100 cars per hour.

But profit margins began to fall in the 1970s, so employers were no longer willing to put up with the gold plating. Chrysler Corp. set the precedent when, in the fall of 1979, it asked the UAW to open its contract. A staffer for a different international union lamented to Labor Notes, “After Chrysler, everything changed.”

It was a special circumstance, to be sure: Chrysler was in trouble and approaching the government for a bailout. What was unusual was the UAW’s easy acquiescence. The concessions were not big by today’s standards. But they set a tone.

A couple months later the UAW took larger concessions at Chrysler, mandated by Congress as the condition for a loan guarantee to the company, and a year later, workers took even bigger ones—a $1.15-per-hour wage cut. UAW President Doug Fraser was placed on the Chrysler board of directors; that was the trade-off.

In early 1982, with the economy in recession, the UAW opened its contracts with Ford and GM as well. GM President Roger Smith had intoned, “You cannot have a two-tier wage industry.” For GM workers to earn more than Chrysler workers would not be competitive.

HELPING THE COMPETITION

UAW leaders said they were better off bargaining early than waiting till they had the right to strike later in the year, at expiration. In the name of pattern bargaining they brought Ford and GM workers down closer to the Chrysler level.

GM had made a third of a billion dollars in profits the previous year.

These concessions didn’t happen without big fights within the union. A coalition called Locals Opposed to Concessions was formed at GM. At Chrysler members voted up concessions by just 59 percent, at GM 52 percent.

Rank-and-file members tended to be more skeptical about management demands than union leaders were. Leaders complained that members couldn’t see the big picture. Members—who interacted with management ever day—suspected they were being taken for a ride.

Light bulbs soon were popping over employers’ heads. The rush became a stampede. If profitable GM could get concessions, anyone could get concessions. A few of the profitable employers to take advantage were Kroger, UPS, Caterpillar, Texaco, and Iowa Beef.

THE HOPE TO SAVE JOBS

Concessions were sold as a way to save jobs. It’s easy to see that they didn’t work. Still using our UAW example, at GM there were 479,000 production workers in 1979. Today it’s about 49,000. That’s a decline of nearly 90 percent.

There are many, many reasons why jobs declined in the auto industry and others, and clearly concessions did not address those reasons.

The hope of saving jobs was in any case just a hope. Companies did not promise to retain certain numbers of jobs. The vote for concessions was a Hail Mary pass, with workers always hoping their company would be the exception.

At Braniff Airlines, for example, workers took a 10 percent wage cut and a year later, Braniff was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy, with 9,000 jobs gone. All concessions accomplished was to get workers working cheaper for a year on their way to a layoff.

Why couldn’t concessions save jobs?

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Bigger forces. The financial difficulties companies faced and the big structural shifts in the economy were far bigger than anything concessions could address. A Ford vice president admitted, “The factors outside collective bargaining far outstrip the gains we can make in wages and benefits. We could cut wages in half and still be uncompetitive.”

Over the next decades employers automated and shifted jobs abroad or to lower-wage areas of the U.S. Concessions did nothing to stop those trends. In fact, the wage cut you took may have helped the employer buy his next robot.

Domino effect. Concessions were unlikely to save individual companies because of the domino effect. When one employer gained concessions, the competition demanded them too. All that was accomplished was lower wages all around.

Demand. Wage cuts hurt the demand side of the economy. Workers with lower wages can’t buy as much.

Today the economic disaster we’re facing is larger than either the recession of the early 1980s or the Great Recession of 2008. Demand for all sorts of goods and services has fallen like a stone. You could reduce the wages of airline workers, for example, to zero and that would not increase customer desire to travel by plane.

What about “strong language”?

The pretend job security in some concessions contracts was so full of loopholes that it was worthless. If it said “no job cuts due to outsourcing,” it wasn’t hard for management to think up another reason for layoffs, or to let jobs disappear through attrition. Or just to violate the spirit or the letter.

GM contracts contained language disallowing plant closings, so soon the company began to “idle” plants instead. The thesaurus was employed: by 2018, targeted factories were “unallocated.”

OTHER CONSEQUENCES

Besides the fact that they don’t save jobs and they do cut pay, there are other reasons not to make concessions:

The first ask isn’t the last. Companies come back for more and the second demand is usually more audacious than the first. Why not, if the union has shown itself willing?

Concessions cement work rule changes that outlast the money givebacks. Companies weren’t dumb when they demanded to shrink workers’ rights, autonomy, and moments to breathe.

The media in the 1980s was in love with the phrase “onerous work rules.” These contractual rights were presented to the public as featherbedding. A worker’s right to bid on a better job produced “churning of the workforce.” Why should employers have to put up with that?

Work rule concessions simply made it harder to have a decent work life. They were about getting more work done with fewer people, reducing the importance of seniority, cutting break time, and giving employers even more authority to run the workplace in a dictatorial fashion.

Workers don’t get anything in return or if they do, it’s a poison pill. In the 1980s what the union got was a labor-management cooperation program. This was touted as a great victory: at a point when the union was weakest, handing over money and work rules to the boss, it was somehow simultaneously making a great gain in power—more “say” over conditions at work.

In fact, the cooperation programs—Quality of Work Life, Employee Involvement—where workers sat down with management to discuss how work could be done “better,” were hotbeds of manipulation where management would steer workers to the job-cutting “solution.”

The desire was to move workers off an us versus them mentality and onto a “how can I help management” mindset. Worker was pitted against worker, the suck-ups versus the dinosaurs.

Concessions undermine solidarity and undermine the union. They promote the idea that the union’s job is to help management and to compete against workers at other companies. They create bad blood with those workers, when instead unions should be strategizing with them to resist together.

When the concession takes away from new hires—by creating two-tier wages, for instance—it creates bad blood inside the union. And concessions make it hard to convince the unorganized that they should join. They don’t need a union to cut their pay.

CONCESSIONS NEVER ENDED

In the 1980s, companies used hard times to force a redistribution of power in their favor—and in most industries the era of concessions never ended. Now times are very hard again. That doesn’t mean concessions are inevitable.

Unions should learn from recent history. They should not decimate their contracts in the forlorn hope of saving jobs. Jobs are going to be lost in any case—that’s the hard truth.

The question is what sort of jobs, and what sort of contracts, and what sort of labor movement, union members will return to when the pandemic finally eases.

A correction has been made for average wage gains of union workers over the last 36 years. The figure is 50 cents per year rather than 54 cents as reported earlier. -Editors