South Korea: Death of Young Worker Galvanizes a New Movement

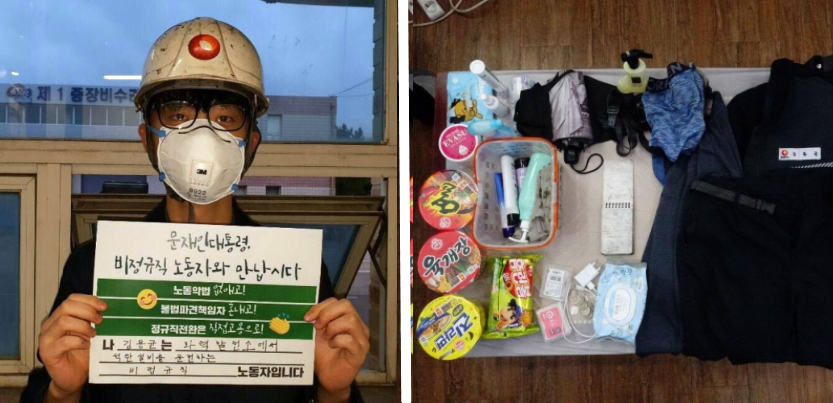

A few days before his death, Kim Yong-kyun joined a “selfie campaign,” posting on social media a photo of himself (left) holding a sign reading: “Mr. President, please meet with temporary workers to repeal unfair labor laws, to punish illegal outsourcers, and to replace temporary jobs with regular ones.” At the time of his death, Kim’s backpack (right) contained a broken flashlight and three cups of noodles, the only meals he could afford. Photos: KCTU.

On the night of December 11, Kim Yong-kyun, a 24-year-old worker, was killed at a thermal power plant in Taean, 150 kilometers southwest of Seoul, after being sucked into a coal conveyor belt that decapitated him.

Only four months into his temporary job, he was killed so that the belt could uninterruptedly run at a speed of 16 feet per second.

Kim was the 15th worker to die at the Taean thermal plant since 2010. All were temporary workers.

VANISHED DREAMS

Long before his fatal fall, Kim was among an army of young, working-class children who had dropped off a rapidly narrowing path to middle-class life. He was born to a modest working family but managed to graduate from college.

However, few good jobs awaited him.

Kim made several attempts to become a low-ranking civil servant, all in vain. The competition was tough: less than three percent of applicants pass the written civil service test, which promises lifetime employment with a pension. Once the norm, such terms of employment are now a rarity in South Korea.

He also earned two engineering licenses in a move to burnish his resume for big corporations, which favor applicants from elite colleges over those from more working-class schools like the one he attended. For all this test prep and licensing, he had to spend his own money or family savings.

Despite his efforts, Kim ended up picking coal droppings as a one-year contract worker, alternating between day and night shifts.

Kim only received three hours of safety education before being deployed on the conveyor belt. He had to pay out of pocket for a safety helmet and a flashlight while taking home less than $1,500 a month without benefits. This was less than half the wage of regular workers, not even factoring in the benefits they earn.

At the time of his death, Kim’s backpack contained a broken flashlight and three cups of noodles, the only meals he could afford.

DEADLY STATISTICS

Kim was collateral damage as the country has turned into a predatory economy that feeds on its temporary workforce. In South Korea, in an average year more than 1,000 workers are killed in accidents at their workplaces, the highest fatality rate among the 36 OECD member countries. About 76 percent of these deaths are of temporary workers.

The alarming official figures likely understate the actual fatalities of temporary workers, as their accidents often go unreported.

In 2016, Korea Western Power Co., Ltd., the owner of the Taean plant where Mr. Kim died, did not report four workplace deaths to authorities in order to reduce premiums for workers’ compensation. The victims were temporary workers who were killed in two different accidents, according to a lawmaker who compared company filings and police reports for that year.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

BIG ECONOMY LEANS ON TEMPS

The origins of Korea Western Power Co. showcased how even the electricity industry, in many countries an anti-privatization bulwark for public security and good jobs, has evolved in South Korea to facilitate outsourcing and to pursue profits.

In 2011, Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) spun off power plants as six subsidiaries to better focus on an exchange where it buys and sells electricity as a commodity with private electricity makers and traders. In 2014, one of the subsidiaries spun off its maintenance unit into Korea Western Power Co. which in turn began to subcontract maintenance work to Korea Engineering & Power Services Co., Ltd, its own subsidiary that it later sold to a private equity firm.

It was KEPCO that hired Kim to maintain the conveyor belt at Korea Western Power’s plant. It is KEPCO that distributes or trades electricity produced by its subsidiaries which have in turn launched tens of smaller subsidiaries or subcontracted to slash costs.

This multistage subcontracting structure left Kim and many other young workers dead or injured as they had to sacrifice their youth working long, risky hours for meager wages without benefits.

Currently, about 46 percent of the electricity production of South Korea, the world’s 11th-largest economy, depends on these temporary workforces.

A NEW MOVEMENT

South Korea elected a human-rights lawyer-turned politician, Moon Jae-in as president in 2017, after months of popular protests that unseated authoritarian Park Geun-hye from office.

Two years after his inauguration, Moon finds his progressive agenda on shaky ground. His peace efforts with North Korea have been stalled by the vagaries of Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-eun. And to date he has made little progress on his pro-labor pledges, such as better job security and limits on subcontracting. Recently Moon’s approval rating has plunged to 29 percent among males in their 20s, though he still enjoys an overall 46.5 percent approval rating.

As their high expectations for a progressive president began to evaporate, many young temporary workers like Kim took matters into their own hands. A few days before his death, Kim and hundreds of others joined a “selfie campaign.” Each worker posted a selfie on social media of him or her holding a sign reading: “Mr. President, please meet with temporary workers to repeal unfair labor laws, to punish illegal outsourcers, and to replace temporary jobs with regular ones.”

The Moon government has apologized for poor oversight in connection with Kim’s death. However, a legislative bill meant to limit subcontracting has remained blocked for years at the National Assembly, where Moon’s plurality party could pass it with help from two minority parties.

Kim’s gruesome on-the-job death is galvanizing the burgeoning campaign to curb workplace fatalities by limiting the subcontracting of risky jobs. The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions and other labor groups will hold a rally on December 22. After the event, they will march to the presidential residence to demand direct dialogue with Moon—just as Kim had wished—over ways to end the deadly subcontracting of labor. After years of declines and demoralization, the once-militant South Korean labor movement is now seeing the rise of a new generation.

On December 27, after a week of public outcries and protests following Kim’s death, the National Assembly passed an amendment to the Industrial Safety Act. The amendment bans corporations from subcontracting 22 types of high-risk job such as metal plating. It also requires the contractor to compensate 1 billion won ($1.2 million) for the on-the-job death of a contract worker. The amendment will take effect in January.

This article has been updated to reflect the passage of the amendment.

Kap Seol is a writer based in New York.