How Brazilian Bank Workers Learn to Dream Bigger

A Brazilian bank workers union uses popular education to spark conversations about visions for the future and inspire bank workers to take practical action.Photo: SEEB-SP

Bernie Sanders’ campaign this year got many union members excited about transforming our economy and fighting for a “political revolution.” How can unions continue that conversation?

Last year in Brazil, I got to see an interesting example firsthand. The bank workers union there has developed a weekend training on how members’ workplace fights connect to a bigger picture.

While the content is important, even more significant is how it’s taught. The method is popular education—a democratic approach that values the knowledge students already hold and tries to break down the hierarchies between teachers and students. (See box.)

I spent a few months in São Paulo as part of an exchange between the bank workers union, SEEB-SP, and my union, Service Employees Local 26 in Minnesota, which is also working to develop popular education programs with its local allies. I left inspired by how the bank workers are teaching themselves to dream bigger.

IDYLLIC LOCALE

The courses take place at an idyllic retreat center about an hour outside the city, in the midst of farms and a forest. Dogs, birds, goats, chickens, and occasionally monkeys stroll the grounds.

The contrast with São Paulo could not be more striking. The air is clean. There are no jostling subway crowds. Participants kept remarking how relaxing it was.

Twenty to 25 union members attend each training. Accommodations are simple; everyone shares rooms. The only TV is in a common room. Food is plentiful, healthy, and eaten together. Everyone sits in a circle for the trainings. When they break into small groups for an activity, people sit in shaded locations outside.

Staffers emphasize that this environment helps provoke bank workers to imagine a different kind of world, one with more time for reflection and leisure. It also encourages people to return for further courses.

Each training takes place over a weekend. Saturday sessions run from 10 a.m. until 1 or 2 p.m. Afterwards participants eat a long lunch, socialize until an evening activity, and then have a party. Sundays begin at 10 and end by 1.

Organizers build in lots of downtime, including frequent half-hour breaks, which they maintain are almost as important as the content. Members have time to get to know each other and informally process what they’re learning.

Saturdays were very interactive and democratic. On Sundays, which tended to be lecture-based, it seemed to me that people got bored and learned less. (Saturday’s party may be a factor!)

The program has three core courses:

Level 1 awakens bank workers to how capitalism shapes their lives.

Level 2 focuses on Brazilian labor history.

Level 3 provokes bank workers to develop a thoughtful analysis of politics, rather than the disgusted aversion to politics that’s typical in Brazil.

There’s also a course on gender, and union educators are developing courses on sexual identity and race.

LEVEL 1: AN IDEAL DAY

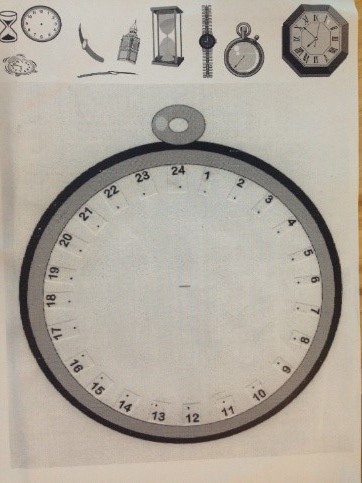

The first course centers on a clock exercise. Facilitators hand out a paper showing a blank, 24-hour clock. Workers fill it out individually to show how they spend their time on a normal workday—for instance, working, sleeping, commuting, or cooking.

Then they discuss their clocks. Gender differences always emerge, with women’s clocks showing more family responsibilities. The point is to get bank workers to talk about why things are structured the way they are.

Next everyone fills in another 24-hour clock representing an ideal day “from their dreams.” In the discussion that follows, the most striking aspect is how small the workers’ dreams are.

Almost always they reduce their work or commute time only slightly. “They cannot get out of their routine,” said elected leader Thiago Lopes. “What they do are small improvements. I also did this.”

Virtually no one creates a day based on recreation or family. Facilitators pose a provocative question: “Can you dream of a world without work?”

“I saw that I couldn’t dream,” Lopes said.

I too found it hard to imagine a world without work. But I came to understand the union doesn’t mean that people should do nothing. Instead, the union is asking, what if we weren’t forced into jobs just to survive?

“Humanized work would not be like today,” Program Director Marcelo Alves told me. “Work today has a painful dimension, and not a dimension of pleasure and personal fulfillment.”

What if we chose tasks because our community needs them, and for the satisfaction of accomplishment? Could workers’ hopes, dreams, and aspirations become the guiding principles to shape a new world rather than the pursuit of profit?

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“We learn the word ‘conditioned,’” said bank worker Marcos Pinheiros. “My family, my friends, and the place where I’ve always lived teach me to think in a certain manner. If I thought in a different manner, everything would punish me.”

The ideas might sound utopian. But evidently this eye-opening conversation about a vision for the future, however distant, inspired bank workers to practical action. Many people I interviewed said it was this exercise that first launched them into union activism.

Fernanda Reis, for instance, attended the training one weekend in 2013. “From that moment on, I became more interested in social questions,” she said. She went on to get elected to the union’s board of directors, taking a leave of absence from her banking job to organize full-time.

As a famous song in Brazil puts it, "The dream we dream alone is just a dream, but the dream we dream together is reality."

LEVEL 2: BRAZIL’S LABOR HISTORY

What Is Popular Education?

Popular education is based on two key values:

- Ordinary people already have knowledge that’s just as important as formal education. Learning starts from the experiences workers bring with them.

- Our methods to organize and educate should be as democratic as the world we want to create. Every participant is both a teacher and a student.

Instead of lecturing, facilitators often pose questions for discussion, encourage people to interpret their own experiences, and supply information that can shed new light on the stories people have shared.

Too few unions in the U.S. use popular education methods. But they’re not entirely absent—for instance, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers in Florida and the Center for Workers United in Struggle (CTUL) in Minnesota use these tools with their members.

To learn more, Paulo Freire’s book Pedagogy of the Oppressed is a good starting point. The Landless Workers Movement (MST) in Brazil has developed an even more extensive program than the bank workers. Read about it in Chapter 3 of Marta Harnecker’s book, Landless People: Building a Social Movement.

The Highlander Center in Tennessee, formed as a labor education center in 1932, is a resource to understand how similar methods have been used in the U.S.

In the next course, bankworkers begin in small groups, imagining they’re creating their union from scratch. They discuss five questions:

- What is the role of the union?

- What is the relationship between the leadership and the base?

- What is the relationship between the union and employers?

- What is the relationship between the union and government?

- What is the relationship between the union and other unions?

When they get back together in the large group, a facilitator provokes participants with questions like:

- There is an unceasing conflict between employers and workers. Do you agree?

- How do you reconcile differences between the members and the leadership? For example, what percent of the union’s members are racist? Does that mean the union is racist?

- Should we try to elect workers to government? Should we have our own political party? How should we resolve conflicts between the party and the union?

Next the facilitator works with the group to create a history of Brazil, asking participants what they know about different periods—for example, “What do people know about the economy of colonial Brazil?”—and then filling in the details that participants miss.

In the evening, facilitators organize a performance, using video, music, and theater to tell the story of Brazilian labor history. The play begins before Columbus, then moves to slavery, emphasizing that workers organized long before unions existed. It portrays the beginning of industrialization, mass immigration, the various dictatorships, and the pro-democracy movement of the 1980s, when the contemporary labor movement was created. (See video excerpts of the play here.)

LEVEL 3: YOUR POLITICAL IDENTITY

The third training, focused on political identity, uses popular education methods the least.

A facilitator hands out a paper with topical political statements, and each person marks whether they agree or disagree. They discuss the questions in small groups, and come to a consensus for each one.

Next the facilitator hands out a provocative newspaper article describing the Palestinian organization Hamas as a movement of pedophiles and connecting it to Brazil’s Workers Party (PT). People are outraged at the facts in this article—until the facilitator reveals that none of it is true, though a Brazilian outlet ran it as actual news.

This prompts a discussion of how the media “colonizes our imagination.”

TALKING ABOUT GENDER

In the course on gender, facilitators begin by handing each participant a stack of stickers—pink for men, blue for women.

A butcher paper in the front of the room lists categories of identity: age, marital status, number of kids, head of household, level of education, religion, sex, gender, and sexual orientation. Everyone places their stickers on the paper to indicate where they fit into each category. A facilitator leads a group discussion.

When I observed this workshop, the only confusion lay in the difference between sex and gender. Several participants explained that sex is biology and gender is sociology, but others remained confused. Some were clearly uncomfortable—but people stayed engaged.

Next each small group got a stack of papers showing different objects (like guns or dishes) or phrases, and had to mark each one as masculine, feminine, or both. Some contentious debate ensued.

One woman said it may be true that household things, like cleaning or cooking, are associated with women—but if women choose that, is that bad? The facilitator responded with a series of questions that mostly boiled down to, “Why do women choose those things?”

The most striking aspect of this workshop, for me, was that the union ran it at all. In my experience, discussions about gender tend to be limited to the academic world or to social movements outside the labor movement. This workshop encouraged me to think about unions as a place to talk about gender explicitly.

Steve Payne is a union organizer in Minneapolis.