Book Excerpt: Changing to an Organizing Culture

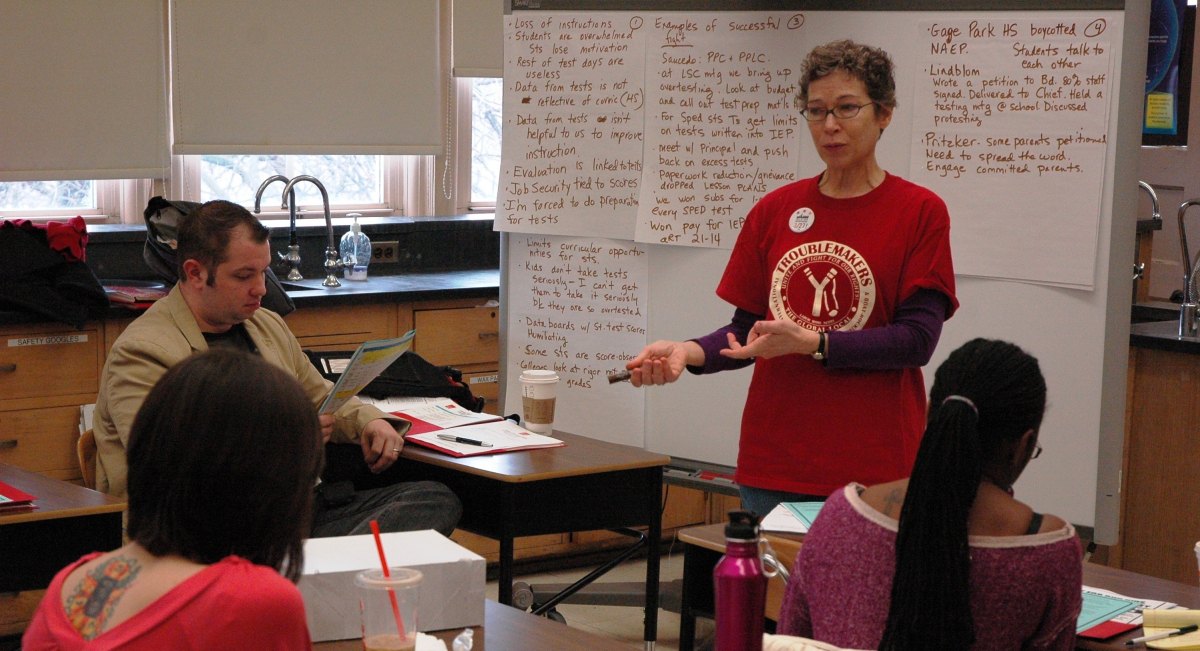

The Chicago Teachers Union trains troublemakers. Photo: Ronnie Reese, CTU.

Our new book, How to Jump-Start Your Union: Lessons from the Chicago Teachers, shows how activists transformed their union. This excerpt tells a little about their internal organizing.

It was clear from the day the rank-and-file caucus took the helm July 1, 2010 that to defend students and members—in fact, to save public education in Chicago—the union would need to be prepared to strike when its contract expired. But with the local’s last strike more than two decades back, in 1987, most Chicago Teachers Union members had never even participated in a vigorous contract campaign.

So the new leaders had to transform their union culture: they had to inspire and train members in every school to step up. And they had two years to do it.

A first step was to rebuild the union as a force within the schools, with delegates (the elected reps in each school) and rank and filers taking responsibility for enforcing the contract.

This went hand in hand with educating all members about the huge threats facing the union and the students—but with the message that winning was possible if large numbers were in motion.

FIRST, CONFIDENCE

The new leaders realized that lack of confidence was their biggest barrier to organizing. Members knew that the sky was falling in on public education. They were not so convinced they could do anything about it. Many members believed that parents blamed them for bad schools.

So many, many union meetings at the schools were spent trying to convince members that parents could and would support them.

Staff Coordinator Jackson Potter sketched out their goal: “We’d like to see members taking on their principals and organizing with parents and the community before they so much as pick up the phone to call the union office.”

One key decision was to start an Organizing Department, which had not existed before.

NEW ROLE FOR DELEGATES

The organizers’ first priority was to make sure every school had a delegate. Many schools had none, or they were not doing the job, though the role of a delegate was minimal: to attend the monthly House of Delegates meetings and report back.

“Very few actually had the skills and wherewithal to organize their buildings to combat any sort of tyrannical decision-making by the administration, or deal with contract violations,” said Potter.

“What we wanted was a web of people to facilitate everybody being involved at the school level.”

So once the slate took office, the duties of a delegate changed. “It was organizing,” said Financial Secretary Kristine Mayle. “And educating. We started education at meetings that was more substantive. We started talking school funding and the power structure in Chicago and charters and big picture reform stuff. That’s what started the delegates being more active.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

To recruit new delegates, organizers went to schools to talk to members in the parking lots or as they were signing out. They called after-school meetings to explain how leaders saw what the members were up against, and they cajoled people to take on the job. If more than one person stepped up, an election was held.

“We talked to people very directly about what we saw as the changing role of delegates,” said organizer Matt Luskin. “Delegates would have to be leaders in their building and organizers of their staff, parents, and school community.”

WORTHWHILE MEETINGS

The most important part of training for new delegates was the organizing attitude.

“Many delegates would complain about members who wouldn’t attend union meetings in the school,” Luskin said. “We encouraged people to think about why people weren’t coming to meetings. Was it the schedule, for instance?

“Many delegates were mad that people weren’t coming to ‘get important information.’ But ‘getting information’ can make for a pretty dull meeting. And how important is it really for me to be there, if it’s just for you to pour info at me? We pushed people to instead make meetings into a place where issues were raised and plans were made.”

The goal was to have a school meeting once a month before or after school, to discuss both building-level issues and larger ones.

TRANSPARENT STRATEGY

“We spent a lot of time talking with people about the ‘whys’ of these activities,” said Luskin. “We tried to avoid just shallow mobilizing—if we were asking delegates to do something we tried to communicate the thinking behind it.

“For example, we wear red shirts on Fridays to show the people who are scared in your school how much support they would have, and to make sure the principals are talking about how widespread it is.”

In other words, the union wanted to make the new strategy very visible. The idea was to win members over to the strategy, not just turn them out to a string of events.

“That big picture discussion of what we are up against and what it would take to win was a key part of school visits,” Luskin said. “This was not the style of organizing where you start with the lowest-common-denominator issue and fight for that, hoping people will get bolder later.

“We said that your jerk of a principal was linked to the increased number of bad ratings teachers were getting systemwide, which then was linked to the overall corporate vision of education reform.

“We said yes, we need to organize to fight on whatever the issue is at your school, but there is no winning on your issue if that doesn’t feed into a citywide fight to change the whole environment we are in.”

To learn much more, order the book. Or hear Chicago educators speak in many workshops at the April 4-6 Labor Notes Conference in Chicago.